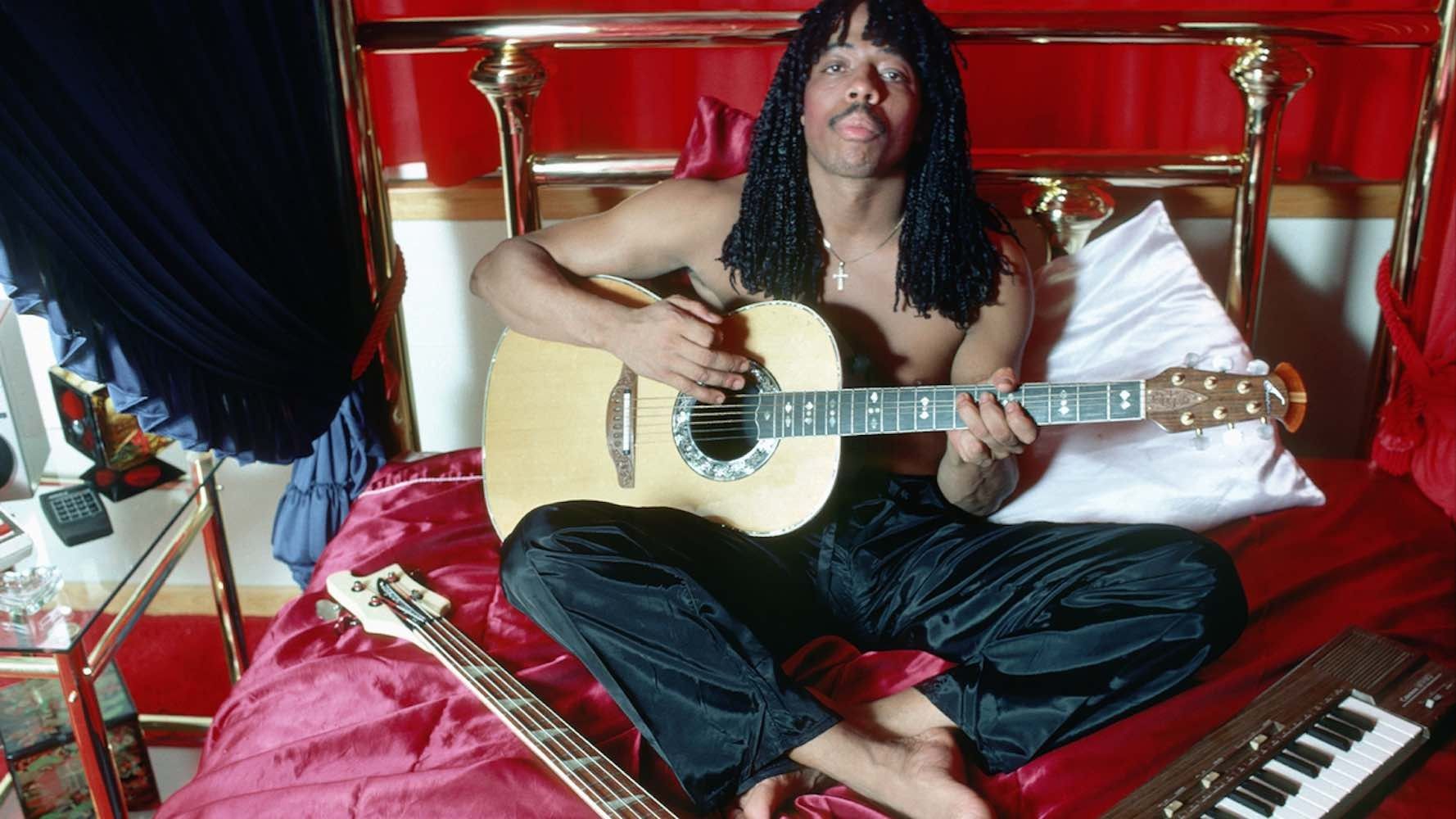

'BITCHIN': The Sound And Fury of Rick James' Captures His Joyous Artistry And Darker Persona [Review]

Bitchin': The Sound and Fury of Rick James gives a nuanced take on the complex dualities of funk star Rick James' identity.

BITCHIN': The Sound and Fury of Rick James is a pretty standard musician documentary. Director Sacha Jenkins doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel. But he does fine tune it. Jenkins’ curation of talking heads and use of archival interviews is more careful and intentional than you typically get in these celebrity pictures. And given the complex dualities of funk star Rick James’ identity, its effort in these regards is essential.

As expected, the documentary, which premiered at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival and will be available to watch on Showtime (although its premiere date hasn't been revealed yet), opens with a collage of comments from James’ family members and fellow celebrities. But set with the sounds of “Mary Jane” and “Super Freak,” these discussions are undeniably energizing. Some of the faces are more immediately recognizable than others, spanning from Ice Cube and other rappers to James’ band members, like Levi Ruffin, Jr. But Jenkins holds back on the fanfare, omitting these figure’s names from the screen until later in the documentary. It’s a subtle touch, but it’s a way of communicating that BITCHIN' is about James’ genuine relationships and impact, not just the number of famous people willing to chat about him on camera.

Of those who actually knew James, the presence of his daughter (and one of the film’s executive producers) Ty is the most impactful. The film opens with shots of her listening to her father’s music while driving a convertible. She pulls up to a warehouse storing several of James’ belongings, then reveals that she hasn’t been here since soon after his death in 2004 because of how painful she knew it could be. It’s an effective way to introduce James’ fraught legacy — starting on a personal level. While looking through his things, Ty begins to open up about the hard stuff, like how absent James was as a father. But she’s able to take joy in his memory, too.

Where Jenkins’ intentions really become clear is around the 20-minute mark, when the people brought in to speak extend beyond James’ social circle. In equal measure to those personal connections, the film is invested in the perspectives of those who studied James impartially in real time; the academics and journalists who have been thinking about his life and work for years. NYU pop music history professor Jason King, USC race and pop culture professor Todd Boyd (AKA “Notorious Ph.D.”), Billboard R&B and hip-hop journalist Gail Mitchell, and music critic Steven Ivory all offer their expertise on every part of James’ persona. And in seeking out these voices, you get the impression that Jenkins is just as well-researched as they are.

This approach becomes especially useful when it comes to exploring the more troubling aspects of who James was. When James’ family and collaborators are interviewed about his drug use and the intense sexual assault allegations made about him over the years, as well as his social and sexual life in general, their answers are frank and direct. With the exception of his ex-wife Tanya Hijazi, who was also implicated in several of the allegations, no one sugarcoats the harm James caused, which is unfortunately rare in discourse about abusive celebrities. It’s a strength of the film that James’ dark past was not only presented as true, but actively contextualized, complemented by stories about his business dealings that corroborated how dangerous he could be, as well as memories from his childhood that may have contributed to his adult behaviors.

A few moments of confusion seemed to arise in Jenkins’ direction, though. The film's strength is in its simplicity, but there are places where it flails, attempting to innovate just for innovation’s sake. Following a current trend in musician documentaries like Stockholm Syndrome about A$AP Rocky and Edgar Wright’s The Sparks Brothers, animation is used to add visuals that would otherwise be unavailable. But here, it’s done tastelessly. For example, in a recorded interview, James recounts his first sexual experience, which happened with his mother’s friend when he was far too young to consent. His voice is played over a crude computer rendering of the adult woman preying on him as his mother bursts into the room in shock and anger. It happens again later in the film while different people recall how James treated women; the computer graphics reappear to illustrate his verbal aggression and physical coercion in the bedroom. Together, these moments seem to suggest that plain discussions of sexual trauma aren’t visceral enough to have an impact, which is misguided — the public doesn’t need these images at all.

BITCHIN' isn’t perfect. But given who Rick James was and how much there is to say about him, the faux pas doesn’t completely erase the merits of the high points. The film closes by weaving together the good with the bad, a careful commentary on how inextricable they are from each other. Rick James was an incredible musician, which gave him a massive platform, which enabled his abuse of others, which made his attempts to get sober and lead a better life more urgent. Nothing here is black and white, and Jenkins’ documentary gives this story the nuance that James — and all lives he affected — deserves.

—

Selome Hailu is a freelance culture writer based in Austin, Texas. She has a special love for coming-of-age films, wacky comedies and anything artsy and Black. You can find her musings on Twitter @selomeeeee.