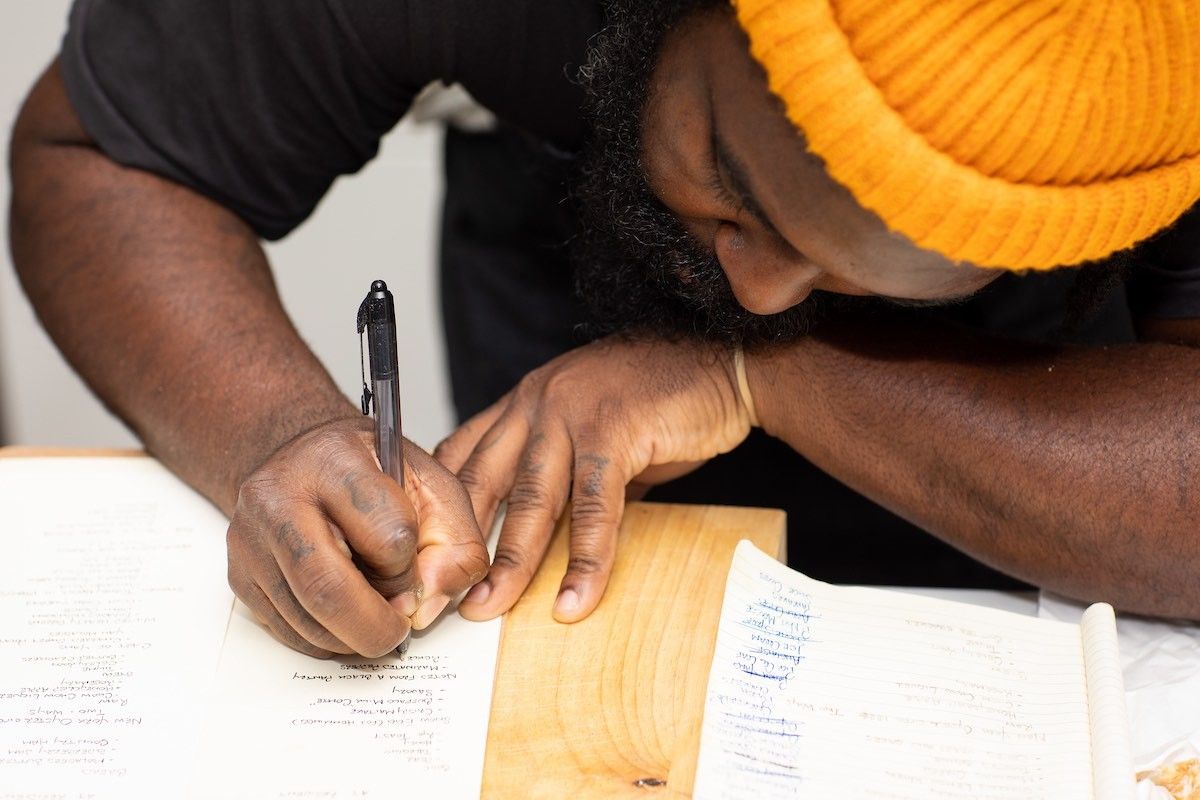

Meet Omar Tate: The Chef Making Dishes Inspired By Jazz, Hip-Hop & Black Literature

From homemade Kool-Aid to smoked turkey necks, Chef Omar Tate has made a career for himself pulling from jazz, hip-hop, and literature to create dishes that give snapshots of Black life in America.

This dish placed in front of me was a matte black lump. Still smoking. Wispy gray tendrils of air were dancing from my plate. Despite the hand-written menu reading "smoked turkey neck on a bed of beans," and the underlying rich, savory and herb-laced scent of slow-roasted meat emanating from the open kitchen, there was something about the dish that made me feel like I was at a crime scene. A gruesomely charred and mangled body over a mound of white-hot ash. But I knew the chef behind the dish had served it that way with purpose and intent. If this was a crime scene, he’d want me to investigate.

Chef Omar Tate has been making a name for himself via intricately conceptual dinners known asHoneysuckle Pop-Ups. In October, I was lucky enough to attend one of these pop-up dinners at an apartment for sale in the Upper West Side in Manhattan. His dinners — which usually seat around 10 people — are forays into the Black American experience, exhaustingly constructed courses with immense depth of flavor that give snapshots of historical events, musical movements, and cultural ideas that have somehow shaped Black life and American society as a whole.

Many of the world’s most notable chefs will take a critical part of their identity and work that into a theme they explore with their dishes. Tate gave me the examples of Massimo Bottura using his Italian heritage to push food sustainability and René Redzepi working his Nordic background into the future of food science. “So, how could I use Black heritage?” Tate asked. “My nostalgia isn't foraging in the field or at my grandmother's feet watching the flour fall when she made pasta, you know?”

Tate’s work ends up being much more modern than nostalgic, resulting in explorations into how the present came to be. Tate himself has no place in a backward-looking lens as his life, realistically, couldn’t have existed in the past. He’s a dark-skinned Black man who was raised in Philadelphia by a single mother. He had a kid pretty young, has been on the unlucky side of a bullet, and has been locked up a few times—a biography he gives willingly, quickly, and somewhat offhandedly. A chef of his pedigree is nearly non-existent in the fine dining world. Yet his personal history, though far from representative of an entire country’s race, has critical anchors that can be expressed through dishes with the same precision, execution and finesse that makes food critics sit back, slack-jawed yet satisfied.

It’s fitting to say he works in edible Black history. The first offering at any of his dinners is homemade Kool-Aid. A blend of pulverized, freeze-dried fruit and sugar awaits diners in a packet at the table, allowing them to dump a powdered red substance in a glass, fill it up with water and stir to taste a familiar hit of sweet, berry-filled goodness. Oh yeah. For Tate, Kool-Aid was that sentimental reference point that kicked off the entire concept behind Honeysuckle. “Whenever it was dinnertime and we didn't have any more Kool-Aid, my mom would always ask me to make it,” Tate said. “It was my job and it signified that the food was ready. My Kool-Aid is bringing together every single thing that I care about in food: agricultural systems, Black heritage, making it contemporary and also fighting stigmas."

“Fighting stigmas” is what makes Tate so singularly gifted in what he does. His dishes are not made for you to taste — though they are impressive in that right — they’re made for you to experience. This is where the Tate-factor comes into play, the litany of references he makes to literature, music, poetry, plays, people, places, and events in his work. He builds his dinners the same way he builds his identity: joining things he’s been exposed to with things he identifies with and things he likes as well as things he wants to question. It’s not about the delicate balance of an oyster stew (creamy and earthy with a grandma’s porridge thickness), it’s about the story he tells while serving it. (It's a story of the freed man who sold oysters near the auction blocks where he would have been sold.) It isn’t about sensing the technique behind a perfectly prepared and dressed sweet potato, it’s about bringing the sensation the narrator of Ralph Ellison’sInvisible Man feels when he happens upon a cart of yams in New York City. In the 1952 novel, the narrator, who is from the South, buys a yam from a street vendor and is overcome with the simple pleasure of the hot yam, intoxicated with pride for his Southern roots, unafraid to be seen eating like a "Black boy from the South."

This connection to Ellison’s novel isn’t theoretical, my third course from Tate was called “Cart of Yams” and it was an homage to this scene. It consisted of charred sweet potato cooked slowly in yam molasses.Though it was served to look like an ordinary yam, it was incredibly soft and moist and parted easily for your teeth then melted on your tongue. It was velvety — though not in a way that seemed engineered.

Tate had a yam cart moment of his own while Honeysuckle was still gestating in his mind. In 2017, Tate was jaded from working as a kitchen manager at the now-closed Once Upon a Tart and wanted to take some time off. So he headed to the South. He decided to crash on a friend’s couch in New Orleans before making his way to his familial roots in plantations around Charleston. He arrived on a Monday, started wandering around and ended up in Tremé where he stopped into a bar. He ordered a Heineken and a whiskey. The place was empty save two old ladies working. The women served him his drinks and then passed him a Styrofoam bowl of rice and beans with pork tail. The three started talking about their lives and the news and Tate couldn’t get over how incredibly delicious the rice and beans were, how effortless the conversation between strangers was. “That was very significant to me, because, at this moment, it stopped being about food as a structure to build a Black menu or narrative around," Tate said. "The narrative's already there. I am the narrative."

From this moment, Tate knew that Honeysuckle wouldn’t be about food trying to fit in a box. It would be about food acting as an extension of the man who was making it. In that way, he couldn’t go wrong because if it was about him, it was always true. As he — like all of us — is a complex and rich individual, his food would be, too. Music plays a central figure in the ideation of his dishes. In creating Honeysuckle, he became an even greater jazz fiend than he had previously been, focusing on music from 1940 to 1963 when jazz was intentionally trying to push boundaries and challenge the idea of what constituted as music. Tate mentions Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie often, while John Coltrane comes up with the frequency of punctuation. In addition to jazz, Tate draws from hip-hop. “Rakim flipping verse, trying to fit as many syllables and ideas as possible into one bar frame was one thing I thought about. But he took that from how Coltrane tried to fit as many different moves in a frame,” Tate said. “Kendrick [Lamar] does the same thing in how he builds his bars. Questlove [of The Roots] does it with drums. How can you layer things with clarity like that? That's what I wanted to do.”

Tate’s favorite dish he’s made is “Clorindy.” It’s named after the 1898 theatre play written by two Black men, Paul Laurence Dunbar and William Cook. The play was the first production on Broadway to have an all-Black cast. Reportedly, the production was thought up over a meal of raw beef, onions, chopped bell peppers, and beer. At the time, however, the Black performers still had to perform in blackface.

Tate’s layered interpretation of this event? As per Honeysuckle’s Instagram, “A beef tartare with chopped bell peppers and onions, candied lemon peel, and grilled scallions. The dressing is squid ink and créme fraîche. The squid ink is a not so subtle nod to the material used to try and obfuscate the beauty of Black folks.” The dish was garnished with black rice wafers broken into the tartare to signify the “shattered ceiling that was penetrated by this production.” Clorindy wasn’t served at my dinner but I asked food writer Korsha Wilson what it was like, knowing she’s had it. She told me:

Clorindy is a mindbending dish. You don't know exactly what you're eating when it's set in front of you because it's all black. As you bite into tender cubes of steak, mixed with bright bits of lemon and earthy, sweet bell peppers wrapped in a squid ink you realize this is a totally different take on a steak tartare. It feels wrong to even call it that. It's completely different.

How Tate can take such dense stories and turn them into remarkably savory and delectable offerings that are both visually and viscerally evocative of their moment is a testament to his skill and conceptual brilliance. Food is thought of as a loving, comforting literal life-giving force. Tate serves up tough love concerned with your pleasure but not your comfort. I suppose that’s where his New Orleans moment comes into play, he’s not here to simply make you feel good. He’s here to give you something of himself. That may not always be palatable–though it is still good for you.

“A lot of chefs are making very pretty plates that are just ostensibly not true,” Tate said. “It can be something very pretty that doesn't taste good, is unethical or is just morally wrong. So, I abandoned pretty and went for beauty...There's beauty in things that are sad and that gives me space, mentally, to make dishes that have a particular aesthetic significance that people can't abandon.”

Cut back to the smoldering, crime scene at my dining experience. The dish was called “Smoked Turkey Necks in 1980s Philadelphia.” It was a charred turkey neck perched on a bed of lima beans swimming in turkey jus served in a deep plate dusted with ash on one side. The plate was served over the hay the turkey itself had been smoked in, it had been set aflame then blown out. So I’m sitting there as a Black woman in a room suddenly smelling of burnt earth and this is placed in front of me: a black neck that I’m supposed to break into with my hands. Snap it and eat it. I felt incredibly uncomfortable at that moment, silently at war with myself for reasons I couldn’t articulate. But I did it, I bit into it and it was moist and delicious and flavorful and my hands were instantly coated with the juice as it flowed shiny to my wrists. The interior of the neck betrayed the cold, dark, dead, unappealing and un-pretty look of its exterior.

Tate’s food isn’t just food; it is empathy and it is education. It is music and it is rhythm. It is jazz’s frustration morphing into hip-hop’s articulation and nodding to all the barbecues that happened in between. It harkens back to an older time while laying the foundation for a more confident future. “What I am trying to do is use history to create or impart new ideas about what's happening with us right now,” Tate said.

When other chefs or diners suggest to him that his turkey neck dish should be made to be more photographable, shinier, welcoming, he tells them they just don’t get it. “It's supposed to look burnt and forgotten about and not cared over,” Tate said. “But then when you eat it, you get this range of flavor and umami and care. To me, the look of it is what happened to people, and the care that you taste in it is what the people actually were. They were people with depth and character and flavor and salt, and all these things matter.”

Chef Omar Tate's next pop-up dinner will be held on January 13th. Reservations are $150 a seat. RSVP here.

__

Nereya Otieno is a writer, thinker and ramen-eater currently based in Los Angeles.