A New Book Corrects Black Women's Exclusion From Popular Music

In her new book, Liner Notes for the Revolution, author Daphne A. Brooks places Black women at the center of popular music.

If you find yourself in a conversation with Daphne A. Brooks, I highly recommend you have a pen and paper handy. Or your notes app open. If you are watching or listening to one of her talks online, your browser will surely be afflicted with what I’ve coined the “Brooks Wake of Open Tabs.” Her knowledge is simply so plentiful, you’ll be scrambling to hold on. Thankfully, the Yale professor, author, editor, music aficionado, and all-around-president of the Cool Kids’ Table has released a new book, Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound. Published in February, the book is a careful and extensive — though not exhaustive — highlight of the immense contributions made by known and unknown Black women in the evolution of American popular music.

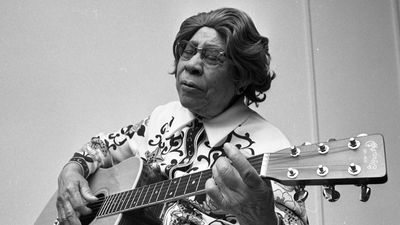

Brooks focuses not only on musicians but also the music critics, journalists, fans, and advocates who have been cheated or wholly omitted from the public record. She covers the likes of Mamie Smith, the first Black vocalist ever to record the blues; Abbey Lincoln, a bonafide pinup girl who morphed into a jazz vocalist and civil rights activist responsible for shaping major Black feminist thought practices; and literary powerhouse Zora Neale Hurston, who is depicted as a cultural sound archivist in addition to wordsmith. Brooks shows how many Black women were not only left out of the historical canon but that — if they were lucky enough to be included — their contributions were often trivialized and not regarded with their true cultural weight.

"I moved from telling a story about the sweeping history of Black women in popular culture to a story about why we don’t have that book yet," Brooks told me over the phone earlier this month. The deeper record that Brooks reveals is the backbone of today’s Beyoncés, Megans, Jazmines, Syds, Janelles, and H.E.R.s. — and all the clever easter egg salutes they give to the women who came before them.

From scholarly conference to published pages

The idea for Liner Notes for the Revolution has been on Brooks' mind for over 10 years. A seminal event in its creation was a 2004 event called “Critical Karaoke” at the Museum of Popular Culture’s — then called the Experience Music Project — Pop Conference. The conference session invited an exclusive cohort of music and cultural thinkers to present a song that was important to them — but the presentation could not last any longer than the song itself. “It demanded having a concentrated, fine ear that had to draw out the synecdoche,” Brooks said. “I had to understand social and historical events that are tied to my own attachment to the song… those listening practices were emergent in the early days of how I was thinking about this book. And they were practices that I went back to again and again."

This way of thinking in context is evident in Brooks’s work. From her 33 ⅓ series contribution about Jeff Buckley’s Grace and her study of public performances that reframed racial narratives via her book Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910 to her numerous essays and articles around the web and in print, Brooks continuously takes cultural subjects and puts them in conversation with personal intimacies, other cultural artifacts, historical factors, and critical thought leaders. It’s why Brooks’ work does such an exemplary job of filling in gaps and shining a well-deserved spotlight on the overlooked bastions of culture — particularly Black culture. She looks at them as an active part of an evolving zeitgeist, one that is improved and made more holistic by the inclusion of varied perspectives. "Part of my ethical politics and my methods as a critic are rooted in these jazz studies principles that involve thinking of the work that we do as an ensemble,” she said. “What happens in the context of working as an ensemble is that you take your solo work, your moments of leaving your individual imprint on the music — but those solos are always built-in relation to the other players. They’re building on the ideas and intellectual statements of the other players in the round."

For a book like Liner Notes for the Revolution, this is an instrumental practice. While unearthing the critical Black women from music’s past, she documents the essential Black voices of music’s present. (Hence the “Brooks Wake of Open Tabs.”) The dynamic legacy of Abbey Lincoln and the little-known sonic archiving of Zora Neale Hurston are presented in tandem with the revelatory mind of Thulani Davis, the potent lyrical philosophy of Fred Moten, and the galactic manifestations of Janelle Monáe and her Wondaland crew. As Brooks told me, "those Black feminists archivists, critics, and curators offer some sort of counter-narrative to the white male critics across the 20th and 21st century who have been telling the story of Black sound."

Reviving what's been lost

“Why don’t I know this already?” was a persistent thought I had while reading this book. “You know, there was a whole portion of sonic American life that was cut off from the root," Brooks said. "In the recording industry, what was missed out on was Black women being able to curate their own sounds, play leadership roles with regards to curating the ranks of artists who were signed to labels and given greater platforms to share their art with us. We missed out on women critics who had specific tales to tell about the resonances of the music they were hearing from their own sociocultural worlds.”

Brooks’ definition of a critic is a bit more nebulous than one found in a dictionary. She repeatedly references the importance of fans and ardent listeners to the keeping of cultural archives. "All of these different kinds of listeners — musicians to public intellectuals to Black girls in record shops in the Jim Crow era like my 94-year-old mother — their listening practices mark entire histories of valuing culture," Brooks said.

At first, I’m a little confused by this. But then I recall reading some critics in Spin, Rolling Stone, and The Fader when I was younger.When I think about these critics, I realize I know more about their ex-girlfriends, hangovers, or hungover cross-country drives for their ex-girlfriends than their opinion about the actual music they were critiquing. They were, by and large, white men and their personal lives were inseparable from the public presentation of the music. When race came into play — say a white male critiquing a Black female artist — that often resulted in her music being presented based on its use to him, not always the artistic merit. A great deal of music criticism makes the critic a central character, which is completely fine, but not when there is only one type of central character. My young, Black girl thoughts about music from that era are forever tied to their lives and, what’s more, their ways of living to that music is normalized for me. A critic can’t change the way music makes you feel, but critics shape what we think about when we think about music. That’s an incredible amount of power. One that Brooks is actively extending to Black women of the past and future.

Catalyst for Change, correction of the record

For Brooks, it seems broadening that framework exponentially improves the legacy of the art itself. “The book is a catalyst for change in the hope that it encourages those of us writing about popular culture to widen the lens through which we explore the music,” Brooks said. “Consider the central role that fans play in producing knowledge about the music as well as the artists themselves. They step into the role of historian, the archivist, the curator."

While the book strives to spark change, it also acts as a correction of the record. It’s no small detail that a Black female Yale professor, not yet in her mid-50s, penned this book and published it with Harvard University Press (HUP). While the choice of publisher somewhat limits accessibility for the full public, it does place this veritable tome (and all the names in its pages) on the shelf they’ve long been excluded from. "I originally signed with Harvard because, in academia, it was the home of many landmark popular music studies scholars and critics. All of whom were men,” Brooks said. “I felt like it was important to break that ‘old boys club,’ and I say that very affectionately. To have a Black feminist woman’s study of popular culture permeate that homogeneity within the HUP catalog was important to me." The book was also edited by the HUP Editorial Director, Sharmila Sen, a rare woman of color in the upper echelons of academic presses. According to Brooks, “her team got the story I was trying to tell and championed it."

Creating a Universe

Liner Notes for the Revolution is the first installment of a series entitled Subterranean Blues: Black Women Sound Modernity. Included in the series will be a support to Liner Notes via a feminist reread of the operatic play Porgy & Bess and the “Black women geniuses who were involved in various productions of that show both backstage and in the title role.” The second book will focus on Black women artists from World War II to the 1970s, and include the likes of Eartha Kitt and Nina Simone and their efforts in creating new sounds while shaping modern democracy. The third volume will expound upon an article Brooks wrote in 2008, “All That You Can’t Leave Behind,” about Beyoncé and Mary J. Blige in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The new work will cover Black women in pop from the late 1960s to today and their relation to what’s been named sexual liberation. Brooks knows the scope but values the result. "My colleague, the brilliant Black feminist and queer theorist Kara Keeling, calls it the ‘politics of looking after’ — the ones who have historically been obscured and left behind and erased from the record," Brooks said. "That is the way I approach music writing."

All this begs the question — what the revolution is, exactly? We’ve been informed it will not be televised, but sonic and literary catalysts remain viable options. What is the rebellion this book is preparing its readers for? "In my opinion, this book is making a claim that the revolution relates to the way we tell the story of popular culture — what has unfolded on the lower frequencies,” Brooks said, borrowing a term from renowned author Ralph Ellison. It’s an apt term as lower frequencies are more difficult to hear, but can travel a much greater distance. While these “lower frequency” voices may not always be heard, they resonate for years to come. That’s the change that is happening, and it’s happening via our record players, music columns, air pods, and car stereos. To “listen in detail” — an action from scholar Alexandra Vazquez that Brooks often cites — to these overlooked and impactful Black women with this book as your guide is the antithesis of the last century of American popular culture. It is to perform a revolutionary act.

__

Nereya Otieno is a writer, thinker and ramen-eater currently based in Los Angeles.