From Whitney Houston To Normani: The History of Black Artists Cultivating Pop Music

Through innovation and influence, Black artists have consistently reshaped popular music. From Diana Ross and The Supremes to Whitney Houston to Normani, here is a thorough examination of how Black artists shifted pop throughout the last century.

Forty-five minutes into the 2018 documentary Whitney, there’s an archived interview clip of the late Whitney Houston. It’s the ‘80s — at the height of her success — and she’s addressing the criticisms Black audiences had with her more pop-leaning sound. “What do they want from me? I think music is music,” Houston said. “How do I sing more Black? What am I doing that’s making me sound white? … I’m singing music from my heart. My soul.”

That clip is quickly followed up by a still image of a flyer from Reverend Al Sharpton, which reads “Boycott Whitney ‘Whitey’ Houston.” A few frames later, viewers relive the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards, where the announcement of Houston’s “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” in the Best R&B Urban Contemporary Single by a Female category incites boos from the live audience. Throughout the film, that moment is often mentioned as a leading trauma among the different factors of the superstar’s untimely demise and subsequent fatality.

Thirty years after the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards, there is a somewhat different tone from Houston’s experience reflected on the 2019 MTV Video Music Awards. Arguably one of the network’s most diverse award show telecasts in the past few years, the VMAs featured a plethora of top talent. From Lizzo preaching on the main stage in the midst of “Good As Hell” and “Truth Hurts” to Normani’s name lighting up center-background during “Motivation,” it’s evident a new legion of Black pop stars are taking over.

While those moments were triumphant, trendable moments of televised history, both Lizzo and Normani have received criticism that mirrors what Houston endured. On September 3, Lizzo’s “Truth Hurts” became the No. 1 song on the Billboard Hot 100 — a record-breaking feat for Black women in both hip-hop and pop. However, the climb to the top has been met with criticism, from people labeling her catalog “white people music” due to its pop nature. Normani, on the other hand, has been scrutinized with comparisons to the pop divas who made an impact before her. Some twitter critics have even rebuked “Motivation” for its pop aesthetics in favor of her previous R&B-skewing single with 6lack, “Waves.”

Black music consumers criticizing Black pop stars places unnecessary constrictions on artists who are enduring an uphill battle to survive in an industry that’s reluctant to accept their craft in the first place. These critiques negate and rewrite the longstanding history of Black artists cultivating and redefining the pop music genre as we know it today.

Where these genre debates often enter into a tango is at the constantly evolving definition of what’s considered pop versus R&B. Although the exact moment can’t be traced, many sources determined that the term “pop music” was first recorded in 1926, meaning that a song had “popular appeal.” During that time, music that would be considered “popular standards” would be folk songs, jazz numbers, and Broadway showtunes. Jazz composer Fats Waller existed amongst that era’s mainstream greats, co-writing gems such as “Ain’t Misbehavin,’” while acts like Louis Armstrong also built up their own iconic discography.

By the 1950s and early ‘60s, rock started to take over the mainstream buzz of younger audiences in America and the UK, making both terms synonymous with one another. Billboard magazine began publishing three charts to reflect data on the most popular songs: “Best Seller in Stores,” “Most Played by Jockeys” (radio), and “Most Played in Jukeboxes” (a quasi-equivalent for today’s streaming charts). By the week ending on November 12, 1955, the publication combined those three charts for their Top 100, before publishing their first all-genre encompassing Billboard Hot 100 on August 4, 1958.

Ricky Nelson’s slow-tempoed swing number “Poor Little Fool” became the first official pop song to hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. In the midst of influential acts such as Nelson, Elvis Presley, Tony Bennett, Dean Martin, and Peggy Lee sat The Coasters’ “Yakety Yak” at No. 7. The quartet ranked highest amongst other Black artists who made Billboard’s first Hot 100— beating out Johnny Mathis, Nat King Cole, Sam Cooke, and Chuck Berry. On September 29, 1958, Tommy Edwards became the first Black artist to reach the top of the Billboard Hot 100 with “It’s All In The Game,” an oldie swing song prophesying a couple’s first kiss.

Radio DJs started acknowledging and embracing rock music over time, helping those edgy instrumentation-fueled and risque records climb the Hot 100 faster. However, in the time of legal segregation in the US, racial divides brought about differences in genre classification and limited who were played on stations. From the 1920s to the 1940s, music recorded by Black artists for Black audiences were referred to as “race records.”

Billboard would refer to that genre-specific chart as “Race Records” tracking the “Best Sellers” and “Jukebox Plays” separately. Journalist and editor for the magazine, Jerry Wexler, would eventually coin the term “Rhythm and Blues,” birthing R&B as genre, while renaming a few charts. In 1953, Wexler joined as a partner of Atlantic records, going on to produce for Ray Charles, The Drifters, and Aretha Franklin.

If it weren’t for racial issues in America, one could argue that pop and R&B are essentially the same thing. Both genres appealed primarily to teens and those in their 20s. The lyrics mainly focused on love, and the song structure relied on catchy hooks and earworm melodies. That’s where Berry Gordy Jr. and his record label Motown come into the picture. In the 2019 documentary Hitsville: The Making of Motown, Gordy and his team of songwriters, label executives, and superstars recount how the Detroit music empire blurred the lines of both genres to become “The Sound of Young America” in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

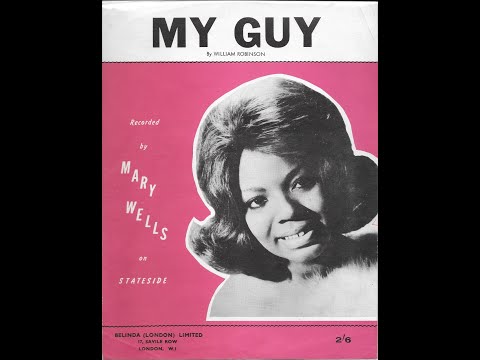

Less than 13 minutes into Hitsville, a recorded argument between Gordy and Smokey Robinson during the post-production of Mary Wells’s 1964 classic “My Guy” highlights a key distinguisher between R&B and pop as genres. The quarrel existed outside of race, and rather on the recording’s mix and profitability.

Robinson favored the edginess and raw feel of the song, arguing, “there must be something in the sound that we’re putting on the streets.” Gordy countered with “If you would have had a clearer sound on ‘My Guy’ it would have went more ‘pop’— it would have stayed on top longer.” Robinson’s lean towards R&B reflected how that genre relies on the raw sound and emotions, the freestyled nature of the voice, and instrumentation that purposely stakes claim in being from a distinct region. Gordy’s thinking of marketability, positions on the charts, and creating a clean product for everyone to enjoy, embodied the idea of pop.

Eventually that issue would resolve itself, as both men created a pop&B formula for the label’s future hits. Gordy took that alchemy a step further by having various departments play a part in the song recording and marketing processes (inspired by his previous employment with the Ford car assembly line in Detroit). Like a factory, Motown manufactured hits like a pop machine by fostering young talent and promoting healthy competition amongst the songwriters and producers.

Gordy would reveal that he received criticism from Black fans when they found out he had white executives on his staff who helped push those records on radio and booked concert slots in cities they normally wouldn’t be played. There was also an etiquette department ran by Maxine Powell, which groomed the stars and gave them a polish to be dignified, clean-cut, and socially acceptable for all audiences to consume and aspire to be like They had essentially been preparing their artists for code-switching, knowing in advance the prejudices of gatekeepers in the industry and audiences who controlled media viewership and music consumption.

Through this formula, The Supremes arguably became the most successful pop act from Motown. Once nicknamed, “The No-Hit Supremes,” their fortune changed in 1964 with “Where Did Our Love Go” reaching No. 1 on the Hot 100. It would be the first of eleven, the most for any girl group to date. What launched them into iconic stratospheres were the trio’s polished and glamorous image, allowing them to make appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show and meet high profile leaders such as the Queen of England.

Eventually, lead singer Diana Ross broke solo, surpassing the rise of another pop-soul maven, Dionne Warwick. Many argue that Warwick is the first Black female pop soloist of her caliber, as she amassed several top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 like “Walk On By.” However, it’s the iconic style, commercial endorsements, more socially conscious records in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and roles in Hollywood blockbusters that pushed Diana Ross to be the de facto blueprint for future Black women who wanted to be pop stars.

In addition to The Supremes, Motown’s other major pop act would be Michael Jackson from The Jackson 5. The Jackson 5’s debut single with the label, “I Want You Back,” reached No. 1, as well as the follow up “ABC”. Like Ross, Jackson would transition into a solo star, collecting his first No. 1 with “Ben” in 1972. Ten years later, his reinvention after his post-disco Off The Wall-era would forever change the game.

Partnering with Quincy Jones, Jackson delivered Thriller, a pop opus that highlighted how the genre started infusing other sounds from around the world to make music even more profitable, global, and relatable. The Thriller-era also redefined the importance of music videos, as “Billie Jean” became the first from a Black artist to be aired on MTV, while the short film for “Thriller” created a worldwide spectacle. Earning eight Grammys for the album and selling over 30 million copies worldwide, Michael Jackson cemented his spot as the “King Of Pop”.

Whitney Houston found her own success during the MTV-era for her immaculate voice, but the route her team took further complicates the debates around Black pop stars. In another documentary highlighting her career, 2017’s Whitney: Can I Be Me, Black label executives were upfront about not only trying to package the star as polished and innocent specifically to reach white audiences, but also hiding from the media her past of growing up in the hood of Newark. Houston’s life seemed like a mystery, as she was media trained not to reveal the private details. At the same time, her team made sure the “music wasn’t too Black sounding.”

Unlike Motown’s strategy of solely focusing on sophisticated images— still allowing for the music to have a unique sound from Detroit’s Black neighborhoods that would infiltrate the market— Houston was manufactured to appease white audiences on both fronts. What’s ironic about that method is how Houston still used her gospel foundations from singing in a church, which she inherited from her mother, Cissy Houston. Songs like “How Will I Know” And “I Wanna Dance With Somebody” may have been perfect pop songs, technically, but — as Houston said — they still had “Soul.” And as time would slowly reveal, the woman behind the songs who made a profit for prejudice-thinking label execs, was a Black woman from Newark, making unprecedented history.

In the ‘80s, Janet Jackson followed in her brother’s footsteps becoming another integral factor in MTV’s pop market. Her third and fourth albums, Control and Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814, gave her a reputation for choreography and socially conscious music statements that experimented with new trends in pop music. Eventually in the '90s, Jackson would be responsible for stimulating the pop economy with black female sexuality and sensuality— rivaling Madonna’s often sought after Eurocentric sex appeal.

Prince would bring a flamboyant stage presence to the scene, and an unapologetic aptitude for sexual content. His fusion of psychedelic rock from his start in the '70s into his sleek brand of funk would define another distinct sound of '80s mainstream pop. With an androgynous fashion sense that pushed boundaries similar to the key of Grace Jones, Prince restructured what it meant to be a fashion icon— challenging what Motown instilled about proper decorum in Black artists. Prince still had grace, but he carried that poise like a badass. He’d push the envelope further in pop music with songs such as “Darling Nikki,” “Sexuality,” and “Controversy.” His outspoken nature also called out record labels for treating artists as “slaves,” as he advocated for all creatives to own copies of their master recordings, a fight still prevalent in the industry today.

The ‘90s saw pop splintering into more trend seeking approaches as a genre. The decade embraced alternative rock as pop, adult contemporary quiet storm as pop (spearheaded by Sade’s sophisti-pop movement in the mid-80s, spiraling into Boyz II Men and Toni Braxton), and even hip hop. Mariah Carey is the perfect example of a pop artist who went through these evolutionary stages as a black musician that decade.

At the start of the ‘90s, Carey followed in Whitney Houston’s path, most notably with pop&B gems “Vision of Love,” “Hero,” and “Emotions.” While collecting a string of Billboard Hot 100 No. 1s and dominating pop radio, Carey was under the watchful eye and control of her husband and manager Tommy Mottola. The Songbird Supreme is often candid about how she had issues not fitting in with white or black peers when growing up biracial, and how that was eventually exploited, as audiences perceived her to be racially ambiguous.

Thanks to “Fantasy” in 1995 and her 1997 LP, Butterfly, Carey had newfound freedom, bringing about the trend of hip hop artists remixing pop songs. The feat had been nothing newly introduced: as Jody Watley is credited as one of the first pop artists to feature a rapper (Rakim) on 1989’s “Friends,” while TLC found massive success with Left Eye rapping on pop hits such as 1996’s “Waterfalls.”

However, Carey’s position as one of the most recognizable pop stars at the time meant hip hop’s commercial dominance was eminent. Hip-hop’s place in the pop market can be traced all the way back to The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” being the first hip-hop song to enter the Billboard Hot 100 in 1979, sparking Debbie Harry to rap on Blondie’s 1981 No. 1 hit “Rapture.” Run-DMC’s “Rock Box” became the first hip hop video to air on MTV in 1984.

Then there was a hip-pop movement in the late ‘80s to early ‘90s with acts such as Young MC (“Bust A Move”), Tone Loc (“Wild Thing”) and MC Hammer (“U Can’t Touch This”). Eventually, gangsta rap would incorporate pop genre tactics with Puffy and Bad Boy Records (“Mo Money Mo Problems”) actively competing against Suge Knight and Death Row Records (“California Love”).

In the late ‘90s to early 2000s, there was a heavy emphasis on teen pop and bubblegum pop. Many associated that time period with Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Backstreet Boys, and N*SYNC. However, there had been Black superstars offering an “urban pop” that competed on the charts successfully alongside bubblegum pop. Acts like Aaliyah (“Try Again”), Brandy (“Have You Ever”), Monica (“Angel of Mine”), Mýa (“Case of thr Ex”), Beyoncé (“Crazy In Love”), Ashanti (“Always On Time”), Ciara (“1, 2 Step”), Alicia Keys (“Fallen”), Kelis (“Milkshake”), and Usher (“Yeah!”) would lead the way with Billboard No. 1 hits, choreographed award show performances and music videos, movie and TV roles, fashion endorsements, dolls, and more.

The early 2000s explosion revealed how Black artists were influencing the culture and shifting the pop landscape even more. Those acts would not be as successful if it weren’t for the talented producers and songwriters. The list is long, but talent such as Pharrell, Missy Elliott, Timbaland, Rodney “Darkchild” Jerkins, Danja, and Kandi Burruss would go on to offer their creative taste to all the aforementioned artists during that wave. As a collective, those acts had been inspired by Michael and Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, and Prince — as they had all grown up watching those stars as kids, eventually performing and working alongside them as teenagers and adults.

Crossover hits seemed natural, but the pop market started to see a reverse in image politics. What used to be labels trying to promote artists as white-aligning, now came accusations and evidence of cultural appropriation, with many white pop stars expressing Black style and vernacular in their image, music, and public appearances. What had also became noticeable was colorism — in which executives and audiences preferred to push lighterskinned Black women over darkerskinned women into the forefront of the industry.

The late 2000s into the 2010s experienced the rise of trap-n-pop, from Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter III to T.I.’s Paper Trail. Kanye West and Kid Cudi further shifted the needle of rappers turning pop singers with 808s & Heartbreak leading into Drake. Rihanna and Nicki Minaj lead EDM and eurodance’s explosion into the pop market (a nod to the times of Black women like Robin S. fostering that legacy in the 90s) — as they endured “white music” criticisms as did Beyoncé with her pop-leaning I Am … Sasha Fierce. Now, all of their efforts are being replicated and reprocessed by a new legion of songwriters and artists of today’s pop from Tayla Parx writing for Ariana Grande (citing these influences) to Normani’s beginnings as a pop star with Fifth Harmony to a solo artist. While hip-hop artists like Migos are, rightfully, winning Best Pop Duo or Group at the American Music Awards, or breaking the perception of pop appearances and hitting No. 1 like Migos.

Since the term was birthed in 1926, and developed into a genre as the decades and generations pass, pop music will always walk a fine line in the complicated debates of art versus money, race in music, and authenticity versus fraudulence. These are challenges the entire music industry faces regardless of genre. Whether an artist or their team has “sold out”or “played the game” is debatable and case-by-case.

What has been proven over time is that through innovation and influence, Black artists have consistently reshaped pop music, despite systemic obstacles, adding to its lucrative economy by keeping the industry alive. Examining these optics, it’s unfair to critique Black artists on these fronts when the name of the game has always been making money by appealing to as many souls as possible. Under that rule, Black artists should win every time.

__

Da’Shan Smith is a pop culture writer based out of New York City. You can follow him @nightshawn101