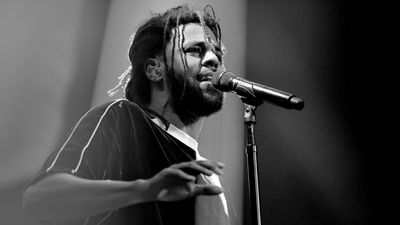

J. Cole’s “Snow On Tha Bluff” Is A Missed Opportunity To Uplift Black Women

J. Cole's new song “Snow On Tha Bluff” is a notable miss from the rapper. The song's commentary is undermined by lyrics directed at an unnamed woman perceived to be Noname.

When the news of Oluwatoyin "Toyin" Salau’s murder broke on Twitter, I became overwhelmed with anger and sorrow. Another one — another nurturer, fighter, Black woman gone because of misogynoir. Salau, a Florida-based activist, had warned us of her abuser, but no one listened until it was too late. As Toyin’s death was shared on social media, Black women voiced the frustration and hurt of seeing a passionate activist killed by the same people she was advocating for. Black men, however, were not as outraged: some gave declarations of needing to do better. Others felt personally attacked and decided to ignore the conversation altogether. That is a tale that many Black women carry: wondering if they'll be heard in a world that refuses to really hear them until it's too late. That want to be heard is often times misconstrued as us being holier than thou — having a "queen tone" as J. Cole put it on his recent, tone-deaf release "Snow on Tha Bluff."

“Snow on Tha Bluff” is divisive. To some, it follows in line with the North Carolina rapper’s brand of insightful and thoughtful rhymes, providing a commentary on the ongoing protests occurring throughout the country against racism and police brutality. To others, its commentary is undermined by lyrics directed at an unnamed woman. Although many believe the woman is activist and artist Noname, who, in late May, called out “top-selling rappers” for not using their platforms to speak out against the injustices currently taking place. But that’s beside the point. In the first part of the track Cole is singling out a particular type of Black woman: one who he believes shouldn’t judge him for not being as “woke” as anyone else, and asking them, “How you gon’ lead when you attackin’ the very same niggas that really do need the shit that you sayin’?”

Despite claims that his stories of women are as misogynistic as the rest, he’s been able to win the hearts of millions of listeners by being careful with the way he pens his misogyny. But when Cole decided to share this song just days after Toyin’s passing — and on a day where two videos of violent acts against Black women were being widely shared — it became clear misogyny cannot be hidden where it is inherently embedded. In “Snow on Tha Bluff,” he has veiled his misogyny with complaints about inaccessibility when, in reality, his education and monetary resources grant him the access he claims to want.

Noname is representative of the type of Black woman Cole is addressing. Many of us have watched Noname’s praxis develop over the years, and she’s been willing to actively listen and do the work necessary to grow and hold herself accountable. When confronted about how her original name — Noname Gypsy — was “racially inappropriate,” she dropped gypsy from her name. When confronted about her original thoughts regarding capitalism, she was willing to engage in the conversation, even now jokingly referring to herself as a "communist." This has led to Noname having a reshifting of sorts that fans have been able to witness in real-time — from her willingness to speak on being a Black artist performing for predominantly white audiences to creating an independent book club that strives to give Black people access to the tools and language that will radicalize them.

“I wanted to popularize radical texts among niggas who don’t fuck with it or have access,” Noname said of her book club in an interview with Okayplayer. “I had no idea that the Black radical tradition was even a thing because I didn’t go to college. I didn’t have access. I just didn’t know. Then after finding out, I’m like, ‘Oh my god we need this to be popularized.’”

Unlike Noname, Cole has openly admitted that he hasn’t done a lot of reading, and it shows on “Snow on Tha Bluff.” The song doesn’t just show a lack of self-awareness — as a college graduate, Cole was privileged with an access to higher learning that many will never have — but it’s rooted in misogynoir, making him the antithesis to a Noname and Black women feminists similar to her. His pro-Blackness feels selective; it’s hard to take in “Snow on Tha Bluff” — and his subsequent handling of the criticism that followed — and not wonder why he didn’t extend a similar want for understanding like he did with XXXTentacion and Kodak Black. (And let’s not forget the time he initiated a conversation with Lil Pump after their “beef.”)

In a 2019 interview with XXL, J. Cole defended his support of the late rapper, who had a history of domestic abuse before his death in 2018.

“We live in a world where everybody wants to be so quick to cancel somebody. But at the same time, people condemn the criminal justice system, which is entirely the cancellation system,” he said. “To me, both of those ideas are fucked up, like, ‘We’re throwing you away.’ Both of those mentalities miss the mark, which is, people need to be healed.”

For harmful Black men who are accused rapists and abusers, Cole is willing to extend understanding. Yet, for Black women, he’s unwilling and, even worse, offended. The thoughts behind “Snow on Tha Bluff” belong to many men and gatekeepers in the hip-hop landscape, and it’s troubling that Cole doesn’t see that. He could’ve done this much differently. He could’ve listened to and uplifted Black women that are rightfully angry, sad, and fearful as they’re awaiting justice for a Black woman who was shot eight times in her sleep in Louisville. He could’ve chosen to form a call to action for Black men to be better in their respective communities. But he didn’t. Regardless of whether Noname is his target or not, he has chosen to project his guilt for his personal failings onto Black women attempting to do the work, and when confronted for his tone-deaf commentary, he doubled down and said he stands "behind every word.”

Cole’s inability to be accountable only reaffirms how deeply-rooted these systemic problems are, and how it’s difficult to reason with someone who doesn’t seem willing to acknowledge how they’re complicit in it. We can no longer do the work for those that wish to selectively listen, rather than actively listen. In order to protect Black women, people must be willing to offer more than verbal support or, in the case of Cole, asking their fans to follow Black women who are doing the work to liberate Black people. This moment should also highlight how we, as fans, look to certain artists as leaders, and who we should actually be amplifying — particularly the voices of Black women, queer and trans people in music.

The real work is a humbling and long endeavor that requires difficult conversations, unlearning, relearning, and complete abandonment of ego. Until there’s acceptance of that, Cole — and Black men who think like him — will continue to fail to listen to and uplift Black women.

—

Simi is a writer and culture communications specialist at Red Bull music. She’s currently based in Brooklyn by the way of Philly, Atlanta and Middletown. She can be found on all social media platform by @simimoonlight