10 Topics Netflix's 'Hip-Hop Evolution' Should Cover For Future Seasons

Ahead of Hip-Hop Evolution's return, here's 10 topics that the docu-series should focus on for future seasons.

Hip-Hop Evolution, the music documentary series centered around the history of hip-hop, will be returning with its fourth season this Friday (January 17).

READ: A Brief But In-depth Dive Into the 40 Year History of UK Hip-Hop & Rap

Originally airing on HBO Canada in 2016, Hip-Hop Evolution has since found a home on Netflix, with its previous three seasons tackling everything from hip-hop's creation in the South Bronx to the East Coast vs. West Coast rivalry that came to a tragic end following the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. The series not only does a great job of breaking down the music but the environments in which the music was being made, showing that art isn't just created in a vacuum. It is a reflection of the realities that people are living.

READ: The 2010s: The Most Influential Rappers of the Decade

Now, with it's fourth season about to air, what will the show address next? There's still so much to cover, with hip-hop continuing to grow as a genre since its birth in the '70s. Okayplayer has offered 10 ideas as to what Hip-Hop Evolution will hopefully be covering in its fourth season. And even if it doesn't happen to cover those topics this time around, hopefully it will in future seasons.

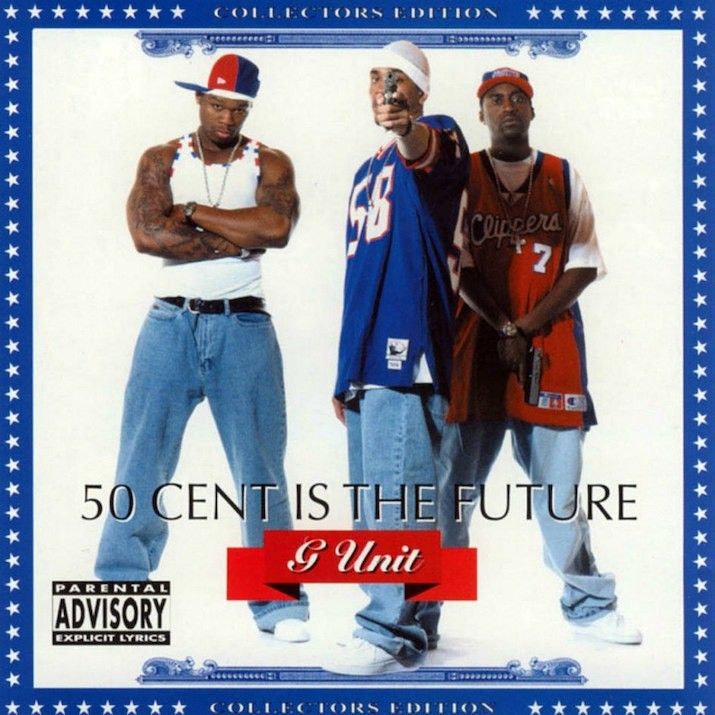

2000s New York Mixtape Culture

From G-Unit's early 2000s mixtape run to Max B's prolific output throughout the late 2000s, there's so much to be explored from 2000s New York mixtape culture. What was it like to hear 50 Cent's "Wanksta" off of 2002's No Mercy, No Fear a year before it reappeared on the rapper's debut album,Get Rich or Die Tryin'? Did The Diplomats realize they had created the blueprint for mixtapes with The Diplomats, Vol .1, which featured the group rapping over recognizable instrumentals while showcasing their original music (like Cam'ron's single "Oh Boy")? How were the mixtapes circulated? Did the five boroughs have their own favorite mixtape series or DJ or was there a unanimous choice? Mixtape culture was integral to not only building a fanbase but a narrative for New York rappers and rap groups, offering a steady output of material that served as the first steps to rap superstardom for artists from 50 Cent to Nicki Minaj. — Elijah Watson

[READ MORE: Did Apple Music Kill the Mixtape Star?]

Pharrell, Timbaland And Missy Elliott's Influence

Rap would be a lot less interesting without Virginia. Producers like Pharrell (and partner in crime Chad Hugo) and Timbaland played with space and uncommon sounds in their production, building a futuristic soundscape that rappers and pop artists continue to hop on today. And then there's Missy Elliott, the brilliant rapper, producer and fashion icon who pushed rap into visual territories that it hadn't been before. Her breakout music video, 'The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)," foreshadowed just how distinct and innovative rap could be. This rap holy trinity is so integral to the genre's history, and laid the foundation for the rappers in Virginia who succeeded them. — EW

[READ MORE: The 10 Best Aaliyah Songs That Weren't Radio Hits]

Alabama Rap

In the mid-2000s, ringtone rap reached a height of virality, where popularity was decided by the number of downloads from teenagers’ cell phones. In 2007, a rapper from Mobile, Alabama achieved crossover success and acquired the #37 Best Song of 2007 from Rolling Stone. “Throw Some D’s,” the debut single from Rich Boy’s self-titled debut album, peaked at #6 on the Billboard 100, and created space for his predecessors, such as YBN Nahmir from Birmingham and Flo Milli from Mobile. — Taylor Crumpton

2010s Atlanta Mixtape Culture

If there was any city that dominated mixtapes in the 2010s, it was Atlanta. Gucci Mane had already made a name for himself in the 2000s with a steady release of mixtapes, and he didn't slow down in the 2010s, releasing Mr. Zone 6, Trap Back, and Trap Godthroughout the decade. But Gucci's prolific output would give way to numerous successors: the back-to-back-to-back critical darlings that were Future's Monster, Beast Mode, and 56 Nightsmixtapes; Young Thug's seminal 1017 Thugand basically every tape he released in the late 2010s; and, of course, Migos' Y.R.N. Thanks to online platforms like DatPiff and LiveMixtapes.com, Atlanta music wasn't only existing in the city but throughout the country and world, foreshadowing the city's inevitable takeover of rap music. These mixtapes reflected how Atlanta rap was changing from its predecessors, as well as building a sound that has since come to define not only rap music but pop music also. — EW

[READ MORE: A Tale Of Two Cities: How Atlanta Overtook New York City As The Modern Hip-Hop Mecca]

Mississippi Rap

Contrary to popular belief, Mississippi provided the musical instrumentation utilized by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five — hip-hop forefathers — on "Freedom," their first Sugarhill Records release. That song sampled “Get Up and Dance” by Freedom, a band from Jackson, Mississippi. Decades later, as the regional sounds of Memphis buck, and New Orleans bounce infiltrated into the state, rap collectives infused the regional influences into a distinctive sound spearheaded by Crooked Lettaz — the rap duo composed of Kamikaze and David Banner. Reese & Bigalow, Queen Boys, 601 Playas, I-55, Triple Threat, and Jewman pioneered the sound of Mississippi hip-hop. Banner was the only one who achieved mainstream success, with signature hits like “Like a Pimp” from Mississippi: The Album and “Play” from Certified. Years later, Big K.R.I.T. brought back “Country Shit,” alongside Ludacris and Bun B, legends of their respective regional sounds in Atlanta and Houston. Out of his counterparts — PyInfamous, Tito Lopez, and Tha Joker — Big K.R.I.T. is the only one to have achieved critically and universal acclaim, a solidification of his positionality as a new pioneer in Mississippi rap history. — TC

Memphis Horrorcore

The '90s saw the rise of horrorcore in rap music thanks to the Geto Boys and Gravediggaz. But Memphis horrorcore was also beginning to crop up during the decade, with groups like Three 6 Mafia ultimately becoming one of the standouts associated with the rap subgenre. The group's debut album Mystic Stylezmaintained many of the signifiers associated with horrorcore: lyrics dedicated graphic violence, the occult, and satan, as well as horror-movie-like imagery and visuals. But it was DJ Paul and Juicy J's production that separated them from their contemporaries. The dark, sludgy and lo-fi soundscapes the pair created served as the blueprint for a sect of underground rap that came in the early 2010s courtesy of SpaceGhostPurrp, A$AP Rocky, Lil Ugly Mane, and others. — EW

[READ MORE: 666 And Inverted Crosses: The Evolution Of Satan's Influence On Rap Music]

Chopped and Screwed

“Without the DJ, it ain’t Screw!” is a verbal honorific of DJ’s Screw legacy in Houston. Screw possessed the ability to transform music through a series of precise yet detailed executions — insertion of slowed, melodic beats that merged into a hypnotic aura where vocals slithered across a psychedelic beat. Screw’s mixing created an avant-garde portal of time travel, which stood out against the fast-paced rap of the 1990s. “The Screw sound is...to feel the music...so you can hear what the rapper is saying...I may run it back two to three times to let you hear what he is saying- so you can wake up and listen, because they are trying to tell you something” said DJ Screw in an issue of Rap Pages magazine. Screwed Up Records, his retail store, started in 1998, was transformed into a cultural landmark in the city of Houston and holds his original catalog of mixes. As his genre migrated into the city’s various neighborhoods, collectives inspired by his musicality — spearheaded by OG Ron C and The Chopstars — have carried on his traditions through their “Chopped Not Slopped” mixes, favored by Academy Award winner Barry Jenkins and Grammy winner Thundercat. — TC

[READ MORE: Solange's 'When I Get Home' And The Avant-Garde Repurposing Of DJ Screw & Houston Hip-Hop]

The Rise Of Auto-Tune In Rap

Auto-Tune might be commonplace now in rap. But there was a time when it was used by a select few, with rappers looking at the voice modulator with contempt and disgust. JAY-Z even made a song about it. And yet, some rappers took to it: from Lil Wayne to Kanye West, the latter of which used Auto-Tune in his genre-redefining fourth album 808s & Heartbreak. Now, it's everywhere, from Future's gargled delivery to Young Thug's high-pitched yelp. Auto-Tune was viewed as a phase that, if some purists had their way, wouldn't — and shouldn't — have lasted that long. And yet, it's still here, rappers using it as a tool to further experiment with their voice and create distinct deliveries. — EW

[READ MORE: Is Vocal Androgyny the Driving Force of Contemporary Rap?]

Trill

In an interview for Noisey’s Back & Forth series, Bun B explained the origins of the word “trill.” “The trill shit started in the penitentiary...the homie [Spoon] when he came home he started using the word. So, that word got associated with the Westside of [Port Arthur].”

Originally from Port Arthur, Bun B has led “Third Coast” rap — composed of Houston and cities surrounding The Gulf Coast — since UGK signed to Jive Records in 1992. An ambassador of the Houston sound, trill’s impact influenced the sounds of legends like Three 6 Mafia and 8Ball & MJG and contemporary stars like A$AP Rocky and Megan Thee Stallion. — TC

[READ MORE: Megan Thee Stallion is Houston's Q-Tip-Approved, Anime-Loving Rap Sensation]

Louisiana Rap

On Solange's A Seat at the Table, there's a skit where Master P illustrated a conversation with his grandfather, a war veteran, his rationale behind calling his label No Limit Records. “My grandfather, he said, 'Why you gon' call it "No Limit ``?'' I said, "Because I don't have any limit to what I could do." Originated in The Bay, Master P migrated No Limit Records to his hometown of New Orleans where he fostered hometown talents into platinum and gold albums. Parallel to No Limit’s ascension in mainstream popularity was Cash Money Records started by Bryan “Birdman” Williams and Ronald “Slim” Williams who developed local rappers Lil Wayne, Juvenile, B.G., and Turk into commercial stars. No Limit and Cash Money’s “rags to riches” success was felt in the regional capitals of Baton Rouge and Shreveport. Hurricane Chris of Shreveport and Boosie Badass and Webbie of Baton Rouge achieved Top Ten chart success for their respective singles of “Wipe Me Down,” “Independent (Remix), “A Bay Bay,” and "Halle Berry” throughout the mid-2000s. — TC

[READ MORE: Big Freedia Says No One Is Going To Take Her Twerking Crown]

__

Taylor Crumpton has written for Pitchfork, PAPER, Teen Vogue, Marie Claire, and more. You can follow her @taylorcrumpton

Elijah Watson is Okayplayer's News & Culture Editor. Follow him at @ElijahCWatson