You Can't Tell the Story of Streetwear Without Mentioning Shirt Kings

Based out of Jamaica Queens, the Shirt Kings were ground zero for streetwear. We spoke with Shirt Kings co-founder Mighty Nike about how the brand ushered in an era of big business for Black-owned streetwear.

This article has been handpicked from the Okayplayer editorial archives and included in our Hip Hop 50 collection as a noteworthy inclusion to the genre's rich and diverse narrative. The article has been edited for context to ensure its accuracy and relevance.

Building 534 looks just like any of the other 27 six-story buildings in the Marcy Houses in Brooklyn. Its reddish-brown brick exterior is equally familiar and repetitive, and perhaps even a bit ominous. Built and operated by the New York City Housing Authority in 1949 — and named after former Governor of New York William L. Marcy — this Bedford-Stuyvesant community is, by now, the stuff of hip-hop lore.

On the first floor of building 534 — on the Flushing Avenue side — lived Clyde A. Harewood, aka Mighty Nike, one of the co-founders of the pioneering streetwear brand Shirt Kings. From the mid-'80s to the early '90s there were really only two places that mattered if you were a young kid from the streets who wanted to wear one-of-one clothing: Dapper Dan, who sold costume pieces out of his 24 hour storefront on Harlem’s 125th street, and Shirt Kings, who had a booth at the Jamaica Colosseum mall in Queens.

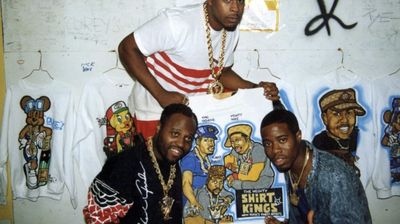

For years, Shirt Kings created bespoke pieces beloved by hip-hop pioneers, drug dealers, and everyday people alike, customizing their looks for street runways where a cuban link, a dookie rope, and a custom airbrush jacket communicated power. Founded by King Kasheme, King Phade and Mighty Nike, the Shirt Kings were ground zero for streetwear. Their local success eventually lead to an explosion of Black-owned independent clothing brands — like Walker Wear, Fubu, and Mecca — that would usher in an era where big brands recognized hip-hop’s power. In short, Mighty Nike witnessed firsthand the long arch of how Black style became big business.

The Birth of Mighty Nike

Despite the calamities taking place around those red benches, the neighborhood that Harewood looked out onto was bursting with style. The Harewood family — immigrants from the Caribbean — moved to Brooklyn and its Caribbean diaspora community in the early '70s. By then Clyde already loved to draw. As a six-year old, he would spend hours in the family’s ground floor apartment in his imagination, immersing in the cartoons in the Sunday paper and carefully emulating the characters he saw on TV: Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Betty Boop. But his absolute favorite was Mighty Mouse, a superhero mouse with bravado and heart. Years later, he would tattoo a Mighty Mouse caricature on his upper right arm with his pen “Mighty Nike'' written underneath. The building ebbed and flowed with neighborhood kids of varying generations and backgrounds. On the fifth floor of Clyde’s building, in apartment 5C, lived a kid years younger named Shawn Corey Carter.

“It wasn’t easy growing up in Marcy,” Nike said, decades later. “Sometimes the neighborhood kids used to tease the Caribbean kids a bit. Marcy Projects essentially had two sides, Flushing Avenue side and Myrtle Avenue bisected by Park Avenue, a wide street. We called each other ‘the other side’ and would go over to the ‘other side’ to see what was happening.”

By the time these young kids of Marcy had reached their teen years, Brooklyn was full on known for its distinct stylings in both style and music. Clyde was hanging out with a tight knit crew of guys including Shawn’s older brother Eric and a prolific rapper named Jaz-O, who was already considered "the best rapper around." The friends were hanging out, rapping, making mixtapes, DJ’ing for fun and experimenting with the Brooklyn sound.

Across the boroughs of New York, hip-hop and all its elements were evolving. MCs and DJ’s were making a name for themselves in parks and clubs and bootleg cassettes exchanged hands spreading the gospel of this new art form while graffiti artists turned New York City public transportation into their own personal canvas.

During his freshman year in high school, at Manhattan's High School of Art and Design, Clyde crossed paths with one of these early graffiti writers. Edwin “Phade” Sacasa was a Bronx kid who was already immersed in the city’s burgeoning graffiti scene, writing "Phade 2" as his tag. They soon befriended Rafael “Kasheme” Avery, a classmate from Queens who was also into graffiti. Manhattan's High School of Art and Design was like an incubator for hip-hop creatives, with artists like Daze, Doze and Lady Pink all attending the school. Whatever was in the water, it fueled a creative force to be reckoned with. And for Clyde, drawing and cartoon work seemed like an extension of what he was immersed in. His work featured iconic characters of the time draped in the hottest fashion of the time. In fact, it was a neighborhood friend of Nike, Jerald “Pet” Guida, who, noticing his two loves of the Nike brand and Mighty Mouse, gave him the nickname Mighty Nike.

“All the characters I drew in high school wore either Fila or Nike. And I started wearing Nike because it was more affordable at the time," Clyde said. "Every time I would get a pair of Nikes, I would change the color on them by drawing and customizing. Then people would ask me where I got ‘em and I would lie and say I got them somewhere in New Jersey. I used to be like ‘I’m the Nike kid.’"

Nike and his crew would hang out at clubs across New York partying at places like Funhouse, The Roxy and Bond’s International. Style was everywhere and, for Nike, the style in Brooklyn was very specific. Gazelle glasses, suede Pumas, Sheep skin jackets and lumberjack hats were the uniform. Bubble goose down jackets, Kangol hats, fat gold ropes dominated the '80s as regular kids and street hustlers alike defined a look that spoke to the entire culture. Those looks were then amplified by hip-hop’s emerging class of MC’s including Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, Kool G. Rap and LL Cool J, who spread that street essence around the world via album covers and music videos.

“We would shop on Delancey Street in the city. We could catch the bus over the Williamsburg Bridge [in Brooklyn] and be right there near Delancey and Orchard streets [in Lower East Side, Manhattan.]," Nike said. "We were really into style so sometimes we would even shop at places like Century 21 or Syms for more higher end stuff where dudes wouldn't really shop. We did what we had to do to look fly.”

Still largely isolated from the eyes of brands, influencers and marketing strategists, hip-hop style developed organically based on being ‘Fresh to death” and a spirit of individuality. You wanted to be asked “where did you get those?” (However, you did not want to be asked “what size are you?” by a dude pointing at your sneakers.) Before the likes of Off-White, Supreme, Yeezy, and the multi-million dollar American streetwear industry of today, kids like Nike, Phade and Kasheme were laying the foundation for something much bigger and global. Even if they didn’t realize it at the time.

Corporate America was starting to take notice of hip-hop’s growing influence but the deals were still at a trickle. Run-DMC were partnered with adidas but the A-list partnerships and endorsement deals were still elusive. A wave of entrepreneurs from the culture would step in to fill that void, in what was clearly a very specific sartorial viewpoint from hip-hop culture. The focus was, above all else, on individuality. Luxury brands were yet to recognize hip-hop’s ability to market and sell product, and even luxury stores didn’t always treat their black customers with dignity. Streetwear's origins in Black culture grappled with major growing pains as the music started to dominate pop culture. And although the intersection of hip-hop and branding was still light years away, one can easily draw a through line right from the Shirt Kings booth to the fashion world’s current obsession with streetwear.

In the mid-'80s, Phade began a business creating silk-screen shirts. His collaborators in that business was an uptown mover who went by the name D Ferg, who would go on to create many early logos for hip-hop companies including Sean “Diddy” Combs’ Bad Boy label. (He is also the father of A$AP Ferg.) Phade and D Ferg wanted to start airbrushing on shirts so they reached out to Nike and Kasheme, who both had just been laid off from their construction jobs. D Ferg started selling the shirts in Harlem and demand was so great Phade started thinking bigger.

In 1986, Nike, Kasheme and Phade joined forces and formed The Shirt Kings, or Mighty Shirt Kings, setting up shop in the Jamaica Colosseum mall in Queens at 89-02 165th Street. It was the middle of the crack era, and, suddenly, monied kingpins with a penchant for wearing their power through jewelry and clothes wanted custom pieces. The rarity would make them stand out on the street and convey a certain sartorial power. The Shirt Kings booth was strategically placed on the lower level of the mall in Queens, right next to Island Jewelers and Eddie’s Gold Teeth. They would hang up their design along the back wall so that the street hustlers, drug kingpins and the folks with money coming to buy jewelry could see their artistry.

“Everybody had money in the '80s. Drug money was flowing. Fat Cat and the Supreme Team — all their soldiers pulling out stacks of money — they all wanted our shirts. And we could customize anything for them," Nike said. "Between us and Dapper Dan, we were the two places to go. We were more on the art and airbrush tip and Dap was more designer and logo focused as he incorporated logos from MCM, Gucci and such.”

Meanwhile, Nike would return to his former neighborhood, Marcy, but things were changing. The crack era had wreaked havoc on many inner-city neighborhoods of New York and many of Nike’s friends and acquaintances from the neighborhood got caught up.

“By the time I came back to the projects, [Shawn] wasn’t a little kid anymore,” Nike said. “He was a street hustler but at the same time the kids in our building were starting to say to me like ‘hey Nike, your boy Jaz-O ain’t the baddest rapper in the projects no more.'"

The Colosseum years

The Colosseum mall — its two floors filled with booths and shops catering to a young hip-hop crowd — was the place to be. Shirt Kings was located on the lower level with a sign that read “No refunds, no matter what you get no refunds, no matter what you get in. Believe Dat.” The atmosphere of the Shirt Kings booth was laid back. Kids from the neighborhood would hang out, listen to music and crack jokes. The vibe was fun but the young entrepreneurs took their work seriously, fine tuning their craft. For Nike, the craft was part of what made the endeavor exciting. Shirt Kings' distinct apparel of hand-painted and aerosol airbrushed sweatshirts, denim jackets, and jeans featured colorful cartoon caricatures — Bart Simpson with a three-finger nameplate ring; Minnie Mouse wearing bamboo earrings; Betty Boop with a gold dookie rope — done in hip-hop style. He challenged himself to draw new characters all the while keeping an ear to what his customers were asking for.

“I had been drawing for a while, and Phade and Kasheme remembered my old drawings." Nike said. “The next thing you know, I’m bringing all my cartoons. Kasheme and Phade were graffiti artists; I couldn’t do graffiti — so that’s where the characters come to play.”

The who’s who of hip-hop began frequenting their shop and word spread quickly. All along, the Shirt Kings worked with an extended entourage of artists to keep up with growing demand. Artists including Derrick, Jef Star, Dupree and Deef — who were all taught the craft of airbrushing — while Tyson, the "main sergeant," was known for adding rhinestones to key pieces. He also taught women artists, like Numita NuNu, Debbie, Sarah and Tiffany, to apply rhinestones as well.

“We had one little air compressor, two airbrushes and a couple dozen sweatshirts drawing and painting away," Nike said. "From there on we found ourselves surrounded with customers who admired our work in which it also caught the eyes of rappers."

Biz Markie was the first rapper Shirt Kings did a shirt for. Biz was shopping at the Coliseum when some kids hanging around the booth got his attention. Biz would eventually commission a design with some Egyptian-themed jewelry. Five days later, Biz came back to pick up his shirt.

“[Biz Markie] spotted us, looked around, saw some things he liked, chatted with us, beatboxed for us. Next thing you know, he said, "Make me a shirt. I'll wear it," Nike said. "I did the shirt and he wore it in Black Beat magazine. He put us on the map and all the other rappers came behind him and wanted something.”

From there, rappers who frequented the Coliseum started to take note.

In 1988, Audio Two released their influential debut album, What More Can I Say?, which spawned the classic "Top Billin'." Dominating the cover is the duo’s air-brushed outfits, a signature look from Shirt Kings.

“Once we did that album cover, everyone looked at us differently,” Nike said. “The hip-hop industry had to respect us even more. We were like the graffiti or street version of Dapper Dan. We were the only two places to get hip-hop fashion wear in that era. Once the rappers would wear any of that stuff, everybody wanted to be like the rappers and wear what they wear.”

Legends like Run DMC’s Jam Master Jay, Big Daddy Kane, Salt-N-Pepa, and Heavy D all became regular customers. LL Cool J once requested they turn him into a cartoon character with his beloved red Audi 5000. He wore it around town and, years later, came back to commission the Shirt Kings to do the outfits for his “Around The Way Girl” video.

As hip-hop was becoming more commercial, Shirt Kings started designing album covers, and magazine pages of early hip-hop magazines. They even designed custom club backdrops that had become the place to be photographed in your finest on an outing to the latest clubs and parties around 42nd street, The Apollo and other notable establishments.

“People out and about would pay to pose in front of the backdrops and takeaway a polaroid picture of the moment,” Nike said. “Before the age of digital photography and instagram, that’s how you showed off."

Streetwear goes corporate

Customization and individuality was a key part of street culture and fashion and, soon, other young streetwear entrepreneurs would set their sights on the growing demand.

While Dapper Dan was making bespoke pieces in Harlem, he inspired a young woman in Brooklyn named April Walker to start her own clothing store called Fashion In Effect, serving the Brooklyn crowd. What followed was a steady stream of brands including Karl Kani, Fubu, and Cross Colours to name a few. Before streetwear was ubiquitous and before the internet gave access to anyone, one had to be in spaces where the looks and inspiration were thriving. A new crop of designers were leading the way with Dap and Shirt Kings setting the foundation.

By the mid-1990s, as urban fashion became mainstream, Shirt Kings' purist aesthetic was at a crossroads. Album and video budgets got bigger and corporate America started to recognize hip-hop’s buying potential. It was no longer a time when three high school friends could easily pursue a dream and set up shop. The stakes were higher and the three partners struggled to adapt their business to the changing times.

“It was tough. Tastes started to change and the airbrush thing wasn’t as novel as it once was," Nike said. "We thought about starting a brand but couldn’t really agree on where to take it.”

Shirt Kings closed its doors at the Coliseum in 1995. Nike and Kasheme set up a small office in a building known as ‘The Music Building’ nearby in Queens but the popular production location soon burned down and the two were left without a headquarters. The two continued airbrushing and expanded to tattoo work while Phade made a move to Los Angeles to start a solo career. In 2003, Kasheme died suddenly from a brain aneurysm. He was just 38 years old.

Postscript

A row of intricate tattoo photos line the wood paneled walls of Murda Ink Tattoo in Hempstead, Long Island. Nike carefully holds a buzzing tattoo needle. Wu-Tang: An American Saga runs silently on the TV while old school hip-hop plays in the background. For years now — and since the original Shirt Kings parted ways — Nike has operated this tattoo shop and applied his penchant for drawing to find new ways of expressing himself. Friends stop by the shop and every once in a while, customers recognize him.

At Murda Ink, the next chapter of Shirt Kings is being written as well. Nike’s airbrush creations sit alongside the tattoo photos, just above the two bubble gum machines.

“I’m always gonna be Shirt Kings, and I’m never gonna stop painting and airbrushing, or drawing because I’m an artist by nature," Nike said. "We created something that forever changed streetwear and how young Black fashion entrepreneurs create."

__

Vikki Tobak is the author of CONTACT HIGH: A VISUAL HISTORY OF HIP-HOP and curator of the exhibition of the same name at the Annenberg Space for Photography and The International Center of Photography. She is an author and journalist whose writing has appeared in Complex, Rolling Stone, The FADER, The Undefeated, Mass Appeal, Paper, Vibe, i-D, the Detroit News, the Library of Congress, and more.