'The Inheritance' Is About The Pursuit Of Black Knowledge And Community Building [Review]

The Inheritance, which was recently played at this year's Blackstar Film Festival, is based on director Ephraim Asili's real experiences living with a radical Black collective.

To be Black is to be constantly engaging with history — both consciously and unconsciously. Even the most apolitical Black person has to walk through life with the knowledge that their treatment from others often depends on historical precedent. It’s a lot to carry with us every day, regardless of how normal it feels for us to do so. But what is much more troubling is what we don’t know: the details obscured by white “intellectuals” with dubious intentions. One could fill a canyon with the number of books, records, and art Black children never learn about in school. It is for that reason that independent research is vital for us to understand where we came from in order to get where we’re going. Ephraim Asili’s debut feature, The Inheritance, is about the pursuit of that knowledge, and the conflicts that arise upon receiving it.

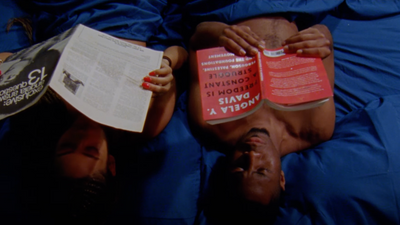

The film, based on Asili’s real experiences living with a radical Black collective, tells the story of Julian, a young Black man who inherits his grandmother’s West Philadelphia home after her death. We watch as he fixes up the house — painting, arranging and looking through a trunk full of Black books that includes Malcolm X on Afro-American History, Charles Mingus’ autobiography Beneath the Underdog, and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. Then, in one of the film’s many artistic interludes, we are treated to images of records by Angela Davis, Ruby Dee, and Stokely Carmichael, all reciting foundational speeches that address Black history and activism. These images and the narrative go hand-in-hand, as Julian tries to learn from radical Black literature and media to fashion a progressive household. After a month of renovation and study, he reconnects with old flame Gwen and invites her to live with him. Together, they try to build a communal living environment based on African socialism. They name their collective The House of Ubuntu, based on South African socialist philosophy.

“Our first step therefore must be to reeducate ourselves, to regain our former attitude of mind,” Gwen says as they’re building their collective, reading from Julius K. Nyerere’s book Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism. Julian then continues the passage: “And in rejecting the capitalist attitude of mind, which colonialism brought into Africa, we must reject also the capitalist methods which go with it. One of these is individual ownership of land. To us in Africa, land was always recognized as belonging to the community.” African socialism is described as “opposed to capitalism which seeks to build a happy society on the basis of exploitation of man by man.” By creating their own community within a shared living space, Julian and Gwen are taking steps toward a more community-focused life. Deep in thought, Julian and Gwen pace as they read, as if presenting the ideas to a full lecture hall. Much of the film is watching them — and other members — learn new information in front of our eyes. It’s information we need to know: in order to build a better future for Black people everywhere, we must unlearn the capitalist mindset. But the characters don’t just read academic writing to us. We also see them try to apply their newfound knowledge in how they run the collective — from household bills to chores.

With a style that reveals influences from the French New Wave, Jim Jarmousch, and Spike Lee, Asili creates a distinct tone, unafraid to be both didactic and avant garde. As the characters speak, so does the house through the colors, images, and words that adorn the space. Alongside these elements, guest lectures and performances are inserted within the narrative to help the collective — and by extension the audience — understand the ideas and traditions that Julian and Gwen are pulling from. We see footage of Shirley Chisholm giving a speech shortly after announcing her candidacy for president. In the present, poet Sonia Sanchez recites Haiku and Tanka for Harriet Tubman. Watching the film feels like attending a class where everyone is participating and learning from each other.

Outside, Asili presents images of the West Philadelphia streets, including various murals, stores, and historical landmarks. Among them is a tablet detailing the events of the MOVE Bombing, which occurred in 1985 within the city. MOVE, the radical communal organization in West Philadelphia that came about in the early ‘70s, is featured prominently in the film, with archival footage of the collective explaining their way of life. News footage of the catastrophic 1985 bombing is also featured prominently in the film. Additionally, former members Debbie Africa, Michael Africa Sr. and Michael Africa Jr. — mother, husband, and son, respectively — all appear and speak to the House of Ubuntu. They discuss the founder of MOVE, John Africa, and his ideas regarding anti-industrialism, communal living, and respecting the environment. This way of living reflects both our past and present, exploring the ways that Black people try to create their own relationships and communities divorced from the suffocating social imbalance that feeds white capitalism.

The Inheritance steadily takes us through the process of building such a specific community grounded in foundational Black texts, all of which explore the transformative power of community in the face of white oppression. It’s a lot of ideas to pack into one film, but Asili designs it all like a museum installation full of images of great pieces of Black music, books, poetry, and art. Weaved in with the more artistic flourishes are scenes of the collective interacting, arguing, and performing together. There’s a theatrical quality of the film that leans into its realism, pushing the viewer to consider the real life possibilities of these conversations. These are the debates we need to be having with each other. This is the way change happens.

__

Jourdain Searles is a writer, comedian, and podcaster who hails from Georgia and resides in Queens. She has written for Bitch Media, Thrillist, The Ringer, and MTV News. As a comic, she has performed stand-up in venues all over New York City, including Union Hall, The People Improv’s Theater, UCB East, and The Creek and the Cave. She can be found on Twitter.