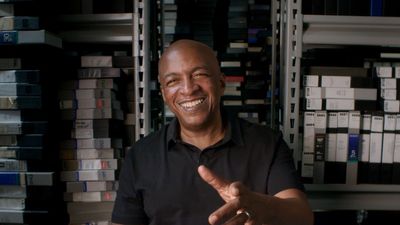

Ralph McDaniels on the 10 Year Journey it Took To Get His 'Video Music Box' Documentary Made

We sat down with Ralph McDaniels to delve into the making of his new documentary You're Watching Video Music Box and the importance of preserving the history of Black music in this country.

Legendary DJ, VJ, and video producerRalph McDaniels has embarked on a cinematic journey to tell the rich history of his groundbreaking television program, Video Music Box.

With over 400 music videos, two feature films, and several documentaries to his producing and directing credits, McDaniels' influence on hip-hop has been ubiquitous for the past four decades. The forthcoming Video Music Box documentary, You're Watching Video Music Box (which premieres on Showtime on Friday, December 3rd at 8 pm) provides an in-depth look into the creation of hip-hop’s first public television program, showcasing its evolution from the early 1980s to present.

After shopping the idea for the past decade, McDaniels found the right team to elevate his vision to completion. Grammy award-winning rapper Nasir “Nas” Jones directed the film with Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men filmmaker Sacha Jenkins taking on producing duties. (This is a full circle moment for McDaniels and Nas: McDaniels directed Nas' first solo video, "'It Ain’t Hard to Tell.") It is the first project in a joint venture between Showtime and Mass Appeal’s entertainment company. Aided by interviews with Nas, Roxanne Shanté, JAY-Z, Diddy, Uncle Luke, and several other hip-hop and cultural luminaries, Video Music Box intertwines their voices with archival footage about the genre’s ascent from fad to global dominance.

Okayplayer recently sat down with McDaniels to delve into the making of the documentary and the importance of preserving the history of Black music in this country.

What is the story behind you and Lionel C. Martin first meeting and later collaborating on bringing the idea of the Video Music Box show to fruition?

Ralph McDaniels: Well, Lionel and me used to collect vinyl records, and we started our own DJ crew. This came from me seeing him in the record store one day, and we realized we kind of knew each other. We’re from the same neighborhood. Then, I noticed he was into records, and I was into records. We were listening to music and had common tastes. This was around the time where people had DJ crews. This was pre-hip hop. One day, we were like, “Yes, let’s put something together.” We put a little crew together. It led to me starting to go into clubs and DJ'ing there. Eventually, when I was in college, I got to work at this internship at WNYC-TV which was Channel 31 in New York City. Lionel was trying to figure out what he was going to do. I think he was studying Pre-law, and he wasn’t quite sure if he wanted to do that. When we were talking one day I said, “Hey, man. Check this out. What I’m doing now reminds me of the whole DJ'ing thing we’ve been doing for a while, except it’s just video and audio.” He came by the station, and he found it interesting. That was the beginning of him getting introduced to producing and directing.

At the time, Lionel and me were consuming everything. If it was music, we had it. Lionel loved little comic books. It didn’t surprise me that he had such a great imagination when it came to directing. I was like, “This dude reads comic books all the time. Now, I know why he reads comic books.” Dude had all the comic books. He was serious about his comic books.

A little later on I said to him, “Look, I got this Video Music Box thing happening. Let’s come up with some ideas.” He started doing some stuff, and we started talking about possibly doing our own thing. When we watched some of the music videos, we were like, “Man, I wish we had done this video. I wish we had done that video.” We wished there was a video for a particular song from back in the days because it would be a classic. We used to say, “Oh, that’s a classic.” Then Lionel said, “Let’s start our own production company, and we can call it Classic Concepts.” That’s how Classic Concepts was born. That was the beginning. We was doing Video Music Box, and then all of a sudden, we started doing videos for Roxanne Shanté, Biz Markie, MC Shan, and all these different artists. We got a little name out there on the directors’ producing tip and that was it. Then, I continued to do Video Music Box because I had a commitment to do that every day. I had to come up with a show. I was doing my thing, and Lionel was more on the directing side because that had another whole entity to it.

What was the thing that inspired you to come up with the concept for the Video Music Box show?

I worked as an engineer, and I wasn’t into production. I was more behind-the-scenes with the camera and being a technical director doing a lot of technical stuff. These tapes would come in and it would be some R&B and disco stuff from the early '80s. In fact, Stephanie Mills was on one of those tapes. I was like, “This is crazy. What is this for?” These artists were performing on a soundstage. This was what record companies used to put out back in that time to give you an idea of what an artist or group looked like live, if you’ve never seen them before. Back then, someone could’ve booked them on a TV show, or just to see the group live, if they wanted to use them for something.

These tapes were not made to be aired, but they were made for whoever was the booker to look at them. I was like, “Man, this would be crazy if we could play this stuff on TV.” My guy named Ed at the station said, “Let’s just put it together.” I created this little video. It wasn’t called a mixtape back then, but that was what it really was. I always treated everything like a DJ. So – we put it all together and said, “Hey, let’s figure out what we can do with this.” Then one day, I took it to the program director and said, “Hey, I think we should air this stuff.” I was trying to describe something that didn’t exist because there was no MTV at that time. If it existed, nobody saw it because MTV came from cable and nobody had cable. So it sat around for a second, and then one day, he came up and said, “Hey, look. Let’s try that idea that you had, and we’re going to use it during this fundraiser that we’re doing.” It did well. People were donating money when they saw the video. I was in shock because it was just an idea I had. But when I saw it actually functioning in real-time, it was a whole different ballgame.

Now, I was like, “What are we going to do with this?” They started to play around with an idea called Studio 31 Dance Party. I responded, “Yo, hold up! That’s my idea.” I already had a job as an engineer, so I said, “Well, look. I’ll be the voice of it for now.” In the back of my mind, I said to myself I got to create my own thing. They were trying to steal my idea. Eventually, they stopped doing whatever they were doing. One day I said, “Well, I’ll do my own thing, and we’ll call it Video Music Box.” They were like, “OK. Give us a second.” Maybe six months went by and there was this show in New York called Hot Tracks that came on. It was basically the same idea. I was like, “We’ve been sitting on this. We could have done this first.” They were like, “OK. What time do you want to do it?” I replied, “I want to do it during whatever time you give to me.” He responded, “We need a show that can come on every day from 3:30 to 4:30 after school for young people." I said, “I’ll take it.” I had never programmed a show before, and I only had like maybe 20 videos. I said to myself, “I got to get some more videos. I got to get some more visuals to make this work every day for an hour.” That’s when I started reaching out to a lot of the artists and the record labels and getting as many videos as I could. Sometimes it was Bruce Springsteen or sometimes it was Hall & Oates. Sometimes it was whatever I could get just to get an hour’s show on. We were always trying to get more Black music in as time went on and hip-hop.

Now, by this time, hip-hop was starting to happen. In the beginning, there were maybe a handful of hip-hop videos because hip-hop wasn’t selling like that yet. For an artist to have a video, they really had to be selling music. If it was something that was new, an artist or group probably wouldn’t have a video for it yet. I was going to record companies telling them, “I heard this song. It’s hot in the streets. Y’all should do a video for Eric B. & Rakim. Y’all should do a video for this song by Kurtis Blow.”

They were like, “OK.” But nobody was asking them for those videos prior to that. I began to put that idea in their heads that now you have a place to play them at. MTV was still not playing hip-hop at that point. We never saw BET because nobody had cable. Eventually, I started getting these little exclusive low-budget videos from the artists, and then I would just go out to wherever they were performing and record them in all locations: performing at a club, some park, or whatever it was and getting interviews. That’s how the whole Video Music Box thing got started. We started it in 1983.

Did Video Music Box air solely in the Tri-state area?

Yes. Over the years, people told me they watched it in different areas of the country. The only reason why I know that it’s true because we were getting letters from different regions and people would make requests by sending in letters. It’d be a long list of any of these artists. In places like Detroit and Florida, the station would upload their signal to this satellite. Some shows were just picking it up live off of the satellite. It wasn’t like they even had a deal. They probably saw the signal and somebody said, “Hey, there’s this show. It comes on at this time. Take the live feed and put it on.”

So, you were able to find the audience, because folks who did not have cable, had access to your show.

At that time, you had your basic channels: ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox was just starting at that point. PIX was the local station in New York like Fox. Then, we had PBS channel 13 in New York. Then, there was these UHF channels and that’s what we were on. We were on channels 25, 31, and 47. Channel 47 was all Spanish. You had to really have your TV in the right direction to get my channel. To get the channel I was on, people would be like, “I can see it, but it’s a little fuzzy.” I told them, “You got to put some tinfoil on it.” [laughs] The stations would go off at a certain time. It would end at midnight and then the channel would just go off. It would just be snow there. Then, it wouldn’t be until maybe nine o’clock in the morning, and you’d hear the national anthem. That’s how they started the day on the channel.

When did you become involved with Nas and his production company to produce this documentary?

I’ve been shopping this idea of a Video Music Box documentary for over 10 years. I was just waiting for the right deal. I started to talk to some folks at HBO about doing the deal two years ago, right around the time when [COVID-19] hit. I remember when I met with them. It was virtual. They weren’t ready to do it. I had a little production deal with this other company, and then the time ran out on it. I reached out to Sacha Jenkins when I was trying to do this other deal. Sacha Jenkins is the director for Mass Appeal. He does a lot of production, and I’ve known him for a while. I’ve helped him out with the Wu-Tang documentary, Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men and helped him out with the documentary Fresh Dressed. Anything he was doing, he’d ask, “Yo, man. You got footage for this?” I’d answer, “Yes, and I’ll send you some stuff.” Then, he’d get an idea. One day I said to him, “Look, let’s see what we can do.” He was the one who had the deal.

Then, I said, “All right. I might have another deal with Showtime.” He already did the Wu-Tang documentary which was on Showtime. I wasn’t sure if it was a Mass Appeal deal or just a Sacha deal. Anyway, it becomes a Mass Appeal deal, and then Nas is in the mix. Nas was like, “Ralph directed my first video, 'It Ain’t Hard to Tell.' That’s my man, I grew up watching Ralph. That would be a dope doc.” All of a sudden, everything fell in line. We worked out the deal with Mass Appeal and Nas was going to be the director.

How many artists, producers, managers, and cultural figures have been interviewed for this documentary?

There are maybe 30 interviews in this documentary which is not a lot. Usually, there would be more, but because of the pandemic and this Hip Hop 50 initiative, which Showtime really wanted to push forward, they were like, “We need to get this done.” The film is being edited right now as I’m speaking to you. I’m going back and forth with the editor right this second. They were looking for something a second ago. They told me, “We can’t find this master.” I’m like, “Hold on. Let me see if I can find it.” That’s how close we are to the deadline. [laughs]

The film has, of course, the original crew, which is Lionel [Martin] and me. Then, we have Nas talking in it as well as being a director. JAY-Z’s in it. Diddy is in it — Fat Joe, Wendy Williams, who was a guest VJ for us when she was on the radio. Uncle Luke is in it. Roxanne Shanté is in it. Willie Geist from MSNBC’s show Morning Joe is in it. Korey Wise of the Exonerated Five is in it and some other big names. The reason why Korey Wise is in there is because, when I was listening to some of his interviews after he was released, he said that he got into a fight with the guy who actually did the crime in Rikers Island. He said, “I was watching Video Music Box.” This was an interview tape with cops, and he was saying that. This was in New York and he said, “I was watching VideoMusic Box and this guy came and changed the channel. We got into a fight because he changed the channel.” I was like, “What did he just say?”

I knew that Korey had just come home and this was around the time of the Ava DuVernay and Oprah [series When They See Us]. I said to myself, “I’ve got to find Korey Wise.” I started looking for him and some girl hit me back up saying, “I know Korey. I’m going to link you two up.” I went to meet him, and he never showed up. Then, one day finally through Eric B., he knew a guy that knew him. Eric B. told me, “He be with us all the time.” I went and me and Korey met, and he told me the whole story.

He said, “I watched Video Music Box every day. When I got locked up, they would have it on in jail. I was happy because that was the only thing that reminded me of being outside was watching your show. Everybody in jail would be watching your show, and if somebody changed the channel it would be a problem. This particular day, for whatever reason, I was in a different room. I wasn’t in the main room with all the other inmates, and I was by myself and this guy came in and turned the channel.”

I remember when Lionel and me did a video for Shaq. Shaq was like, “Yo, I grew up on Video Music Box.” I was trying to get Shaq too, but we didn’t have enough time. The crew that was the original VJs on the show are in it and just a ton of rare footage. Raekwon and Ghostface are in documentary. It’s a different hip-hop story because me and Lionel are not from the Bronx. We came from Queens. I came from Brooklyn, and then I moved to Queens, so our vision on things was a little bit different. It’s a different landscape when you look at where we grew up at. We lived in a house, had a backyard, and it was just different. Some people would say, “You guys had money.” No, that is not true. Our parents weren’t rich or anything like that. It’s that they both worked and spent all their money on a house, but we were still struggling. It was like that, but we did have a little bit of elbow space to explore.

You mentioned the Hip Hop 50 initiative. For almost 50 years now, hip-hop music has been the soundtrack to America’s post-Vietnam history. How do you think hip-hop music has transformed not only American popular culture but the world?

Well, one of the interviews in documentary is with Congressman Hakeem Jeffries. The reason why I wanted to interview him was because he makes so many hip-hop references when he’s talking. I knew him from Brooklyn. After I asked him to be in it, he was like, “Yo, man! I used to watch Video Music Box every day, bro. Are you serious?" When he was talking, I knew he watched it every day. He could tell details about it. I said to myself, “Wow. Look at this young guy who was a hip-hop guy, went to college, and ends up becoming a very powerful person in the government, and he’s there talking hip-hop about [The Notorious B.I.G.] and everything. This is crazy.”

Even before that, I think that the election of Barack Obama was because hip-hop created this kind of unity amongst people. I saw it in the ‘80s when I went to concerts. It wasn’t just a Black thing in ‘85, it was everybody. It was Asian kids, latino kids, Black kids, and white kids. They all knew the words, and they all wore certain types of sneakers and jeans. They were just into hip-hop at that point by ’85 during Run-DMC’s time. It might have started out in the South Bronx, Bed-Stuy, and Brownsville, but by ‘84 or ‘85, everybody was into it. When Barack Obama became President, it was the same concept at that point because those same people were a little older by that time. In ‘85, let’s say they were 20. By the time Barack Obama came, what are they like close to 50? Those people vote.

What has been your approach of going into the archives and finding the footage that will be shown in the documentary?

It was tough because I thought all along that I could do four parts. Everybody was like, “That’s a lot." Nobody atShowtime knew. The guy who green lit it knew, but he didn’t really know. He hadn’t seen me in years. He told me, “Well, let’s keep it to hour and a half. Let’s not go too far.” In the beginning, when we started cutting stuff up and trying to tell a story, I was like, “Maybe this is only an hour and a half.” Then, we got to two hours, and we realized that everything was good. But we had to cut it back, so we just started cutting down. The idea was to tell the story of the early days and a little bit about my mindset of how I even had the vision to do this before it started. We got through that, and then we got into the ‘80s, and I said, “No, we can’t stay in the ‘80s. We got to get to the ‘90s.” The storyline helps us get to the ‘90s. Now, we’re on TV and people have cable. Technology moved it forward and that got us into the ‘90s.

Why is it important to uphold the proud legacy of hip-hop music and to maintain its validity into the future?

The pandemic was good because it made me stop doing everything else I was doing. Even before getting into this whole idea of the documentary, I started digitizing all of these analog tapes that I had. I said to myself, “We have to digitize because I don’t even know what I have. I have it in my head. I have an idea, but suppose something happens to me. Nobody’s going to know.” We started a nonprofit to raise money for digitizing and preserving the culture of hip-hop. The tapes and the images are in what we call the Video Music Box Collection.

The whole idea was to keep hip-hop history alive, from our perspective anyway. I started working on it and began reaching out to people and saying, “Hey, man. We have been digitizing some stuff but not at the best level. We need to do this shit like NFL films does their thing and all of these big networks we know about. Let’s take the same format that they use and let’s make it equivalent to that.” It was expensive. We started doing it and then the idea of the documentary came in between that. It was just out of the blue. Somebody reached out to me, and it wasn’t like I wasn’t ready — I’d already been working on it, like I said before, for over 10 years — but I was in one of those moments where I said to myself, “Let me get my tapes together.”

That just made me dig into the content a little bit faster, and along the road, I realized that we have the rawest elements of what hip-hop looked like. You might have it on some European shows that some of the artists were going over to Europe back in the days, because in the US, it wasn’t really getting that much airplay. In the early Def Jam days, Russell [Simmons] would set up a European tour. Europe was always more progressive than the US was when it came to new music. You might have a show in France that has early performances of some of the early guys, but in the US, you didn’t have any.

But we were the only ones that had a lot of this footage. There were some independent filmmakers that shot some stuff, but on a consistent level, we were the only ones that had it. So, I said, “All right. This stuff needs to get out there and needs to be seen, and even better, I want to be able to link up with the next Lionel Martin as a great director, the next Hype Williams. the next journalists, and make this available in universities like Howard.” Right now, we’re doing something with Rice University. We want to make it so cats can check it out. Plus, there’s hip-hop courses and things in college now.

One hundred years from now this will exist somewhere in some type of institution and some type of museum. The Video Music Box microphone is in the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and they have a section for hip-hop in there. I work with the Queens Public Library, and we do hip-hop programs there.

The only reason why I started doing this was because when I went to colleges, they would ask, “Yo, Ralph. Can you speak about hip-hop?” There usually was a guy who took some hip-hop classes, or he grew up listening to hip-hop, but he didn’t know the culture. I said to myself, “Man, we need to get some of the old pioneers to talk about the culture because they could do it. They could teach these classes.” They still talk about, “We going to make a record.” I’d tell them, “Man, nobody wants to listen to that record right now. You all need to get in these schools and start teaching some of these classes. You can get a couple of dollars.”

How long did it take you to digitize what you have in your archives?

We’re still digitizing. [laughs] I’m talking about hundreds of tapes. It is amazing to me, because when I watch younger people looking at this footage, they look at things like the clothes, the dancers in the back and the artists. They’re looking at different things that I didn’t even pay attention to back then. Whatever it is that they get out of it, it’s all something, and I think that’s a way of bridging the gap. I always say we have to bridge the gap. I tell my peers, “Don’t shoot down these young cats because that’s what was being done to us when we first came out.”

We couldn’t get a hip-hop record played on a Black station. It was like, “No, we ain’t playing that. That is a fad; that ain’t going to last.” That was on Black stations in New York. Literally, they would throw you out of there and tell us to take that hip-hop stuff somewhere else. It took a white company, who had done the research, like Hot 97, and figured out, “Wait a minute. There are way more than Black people that are into this music. We’re going to start this, and we’re going to make this into pop.”

Who have been some of the day-to-day people you’ve been working with on this documentary?

The main ones have been the Mass Appeal folks: Peter Bittenbender, Sacha Jenkins, and Nas. It moved so fast. The one thing that was good was that the pandemic slowed things down. A lot of these guys would have been on tour or doing something else. We got Luke in Miami. I had a really good relationship with Luke because Luke was independent. He wasn’t getting airplay in a lot of places, but we played a lot of Luke videos, not just 2 Live Crew, but H-Town and a couple of other groups that he had. We had this great relationship, and he told me, “New York is where I blew up at sales-wise. I’m from Miami, but I wasn’t getting airplay in Miami. I went to Ralph McDaniels and Red Alert. Those were the two guys that were pumping my stuff on the regular.” It was great to have that perspective because I didn’t know that. I was thinking his music was playing on every radio station in Miami. He said to me, “Miami wasn’t playing my music. The street was but not the radio stations.”

What were some of the main goals that you wanted to accomplish with making this documentary?

At the end of the day, the goal is to create conversation about hip-hop history and develop the Video Music Box Collection. I remember a couple of years ago when I went to MTV. They had MTV classic rock, and I asked them, “Isn’t it time to do a classic hip-hop station? Is there a space for classic hip-hop?” Now, LL [Cool J] has Rock the Bells, which is dedicated to that, but I feel like that’s going to happen as well. I also feel like young people used to look forward to watching Video Music Box. People used to love to look at videos. A friend of mine, and I don’t know if it’s true or not, told me, “You kept the crime rate down from 3:30 to 4:30 because everybody was inside watching your show, man.”

Do you have any future documentary projects that are possibly in the works?

Yes. We walked in there with a couple of ideas. I went to high school with The Feurtado brothers [Lance and Todd], and they were drug guys with The Supreme Team. That’s what all 50 Cent’s shows are based upon. With Power and that kind of stuff. It is based upon these other guys that came later. They were the first guys to do it, and we all went to high school together. They went their way and became these big drug kingpins and did crazy federal time. Their story has never been told but their family members were cops. They came from a middle-class neighborhood and people would ask, “How did this happen?” These guys were dealing heroin and dealing with John Gotti for real. They’re in this documentary too. They’re just talking about how the neighborhood was and that it was nice. I feel like there are so many hip-hop stories that we haven’t touched on yet: the importance of the music changing and the importance of the underground.

__

ChrisWilliams is a Virginia-based writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, Red Bull Music Academy, EBONY, and Wax Poetics. Follow the latest and greatest from him on Twitter @iamchriswms.