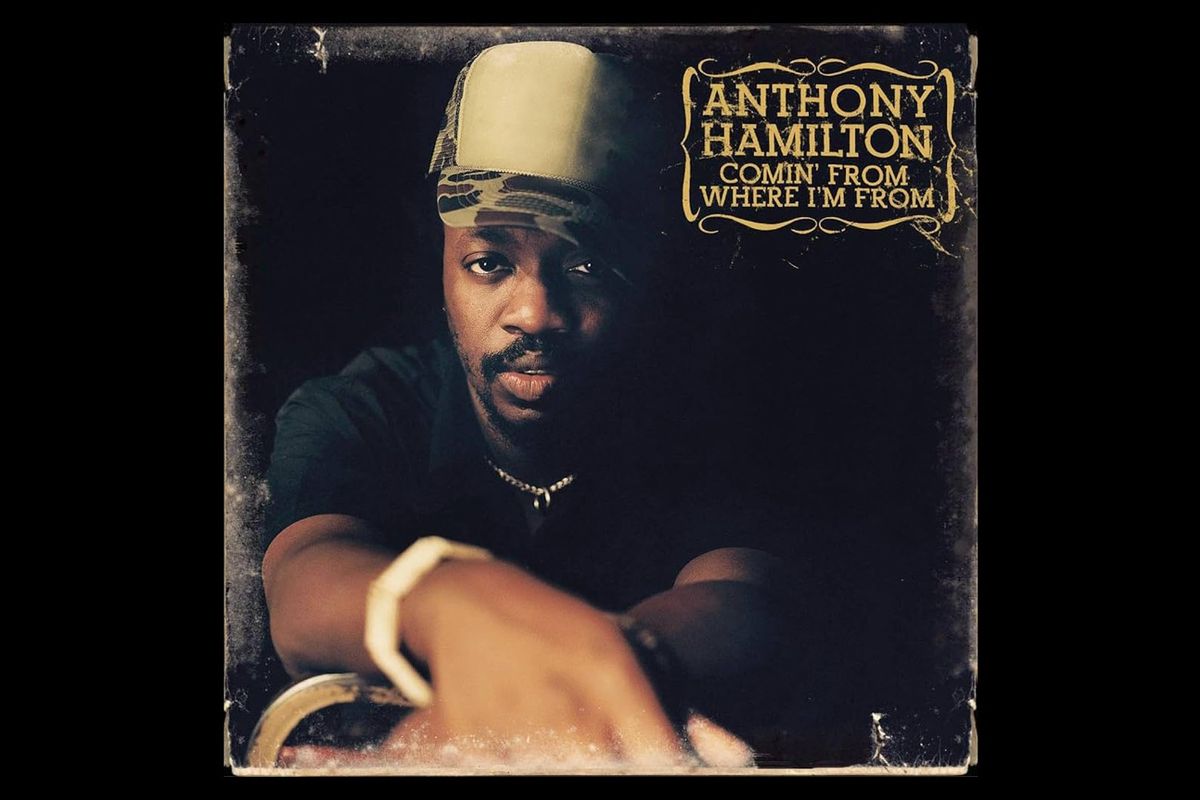

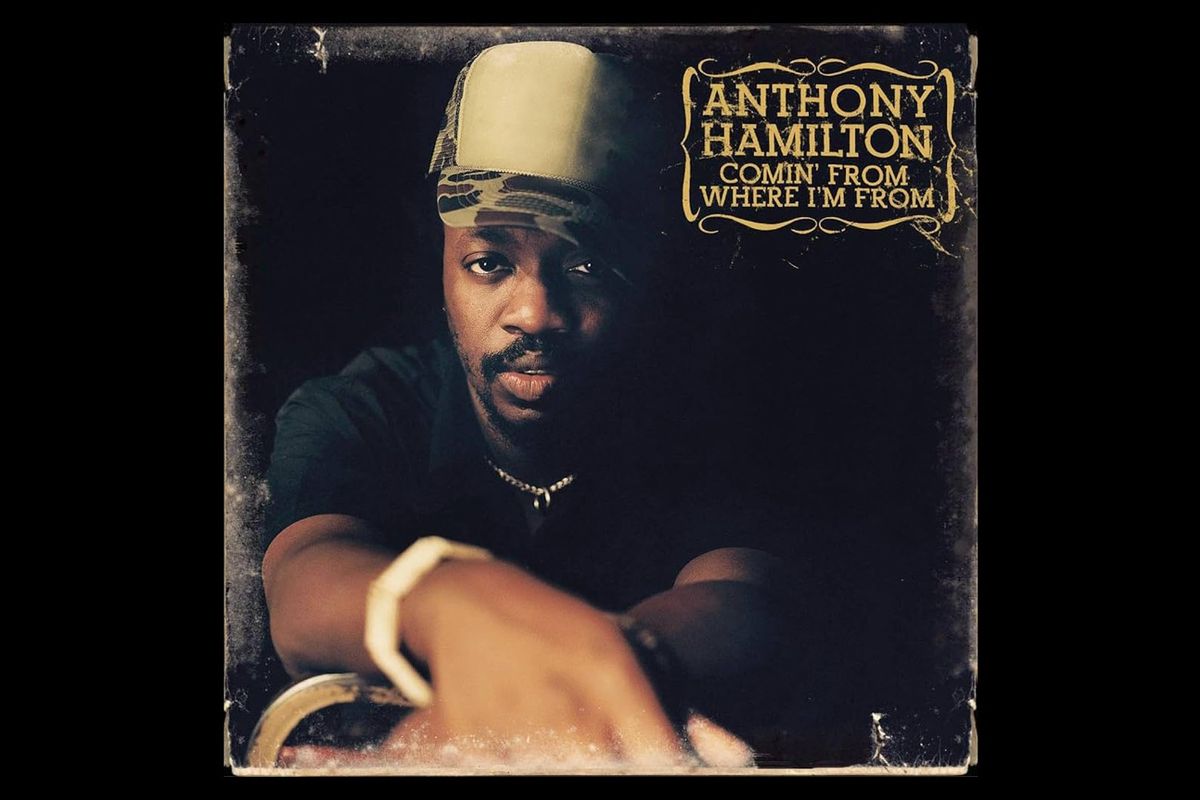

Cover art for 'Comin' From Where I'm From' by Anthony Hamilton.

On the 20 year anniversary of 'Comin' From Where I'm From,' we spoke to R&B legend Anthony Hamilton about the long and unlikely road to a platinum-selling album and what it means to R&B today.

The beginning of Charlotte, North Carolina soul singer Anthony Hamilton’s career was filled with false starts. In 1992, he moved to New York and signed with André Harrell’s Uptown Records, but was eventually shelved. He toured with D’Angelo on his Brown Sugar tour in the mid-'90s and revved back up into a deal with Atlantic’s imprint Soul Life Records in 1999. During his time there he got his first mainstream recognition for his feature on the Nappy Roots single “Po’ Folks,” where his raspy baritone and blue collar fashion aesthetic grabbed eyes and ears. Yet, he was eventually shelved and dropped by Soul Life in 2002. However, towards the end of his tenure there, Hamilton connected with producer Mark Batson (Alicia Keys, Dave Mattews Band). They crafted versions of what would eventually become the songs “Comin' From Where I’m From,” “Since I Seen’t You,” and the eventually Grammy-nominated “Charlene.” “When I played [these songs] for them (Atlantic), they didn't get it,” Hamilton reveals to Okayplayer over a video call. “Thank God, they didn't get it and they didn't have them all tied up in litigation [when they let me go] because it would have taken a lot of the life out of the [eventual] album.”

Hamilton would eventually find ears that “got it” in Jermaine Dupri and So So Def/Arista Records. They’d release those songs as a part of the twelve-track platinum-selling album Comin From Where I’m From on September 23, 2003. Now, 20 years later, Hamilton can only look back upon the lack of belief from his label opportunities as a blessing. Their lack of follow-through not only landed him in the eventual perfect situation, but it also gave his sound more raw energy via the rejection. “I'm glad that they passed up on it,” he proclaims in retrospect. “It’s crazy to me how all that happened. But it wasn't my turn til it was. I probably wouldn't have sang with that much grit had I not had to suffer and sit on my own stuff. I would have probably taken on a whole other sound singing really pretty boring songs that nobody wanted to hear. I’d probably be doing karaoke right now.”

Comin From Where I’m From is one of the most guttural R&B projects of the 21st century. As Hamilton has advanced in his career since, he’s gone in and out of where his sound started. Recapturing the exact magic is impossible, but identifying where it came from can be an interesting process. Okayplayer spoke with Hamilton and discussed how the album solidified his legacy right at the beginning, and how it has aged into even more of a one-of-one classic.

The interview below has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Comin' From Where I’m From has a theme of home and what it means. How was that prevalent when you made it and how does that resonate now?

Anthony Hamilton: Back then it was more effortless. I had become home within myself, and so wherever I went and whatever I sang on, it just came out. I think more about it now because I feel like I have to chase the home I put in the first album with some of the newer stuff. But then, it was just knowing the textures, sounds, feelings, and smells of home and surrendering to that moment.

The title track is about growing up in Charlotte. What was the core feeling or impetus for that expression?

The opening line, “sitting here guess I didn't make bail,” [is about how] sometimes you feel like you are incarcerated within your own situation. Working with Mark Batson, the music touched something deep in me. I wrote from a place that I never knew I had. It was almost like my “once upon a time.” I just started writing and visualizing things that weren't that great, and some things that were really good. I tried to let people know wherever you’re from, it's okay, tell your story.

How did you come to start working with Mark Batson?

I was in the studio working with James Poyser (The Roots, D’Angelo) and a guy named Che Pope (Lauryn Hill). I was in the studio with them listening to tracks and doing a little background here and there. Mark Batson came through, they introduced me and I just heard him play, man. We just bonded. I called him one day when I was heartbroken and Mark gave me a place to come to. The studio on 34th between Broadway and 8th in NYC. I’d go down there every day and he’d just let me write. Mark's almost like my musical godfather.

What happened with the heartbreak that led to some of the first album tracks?

It was a tender spot, man. I had never really felt it like that. It was young teenage love coming into my adult years. I had started to see what people feel when they want to get married and create a family. When that ended, it shattered me. A lot of those songs have a little bit of heartbreak overlay. It was a healing experience (to make them). We had been together for five years and had a son. I wanted to take that energy and create from it. I was like, “I got to own this pain right here and allow myself to bleed on paper.”

Can you talk about the undercurrent of blues throughout the album?

I think it was just an unspoken texture. I don't even think any of us knew at the beginning how bluesy it was going to be. When we were just in the beginning stages of writing and creating it, I think what Batson and I did allowed everybody else to come in and create in that same sonic space. Some people were like, “Wow, I've been trying to do music like this for a long time.” Nobody was doing that and nobody had the voice to make it believable. I think we gave the okay for people to come in and be as down-home as they possibly can be.

What I think is really interesting is where R&B specifically was when the album dropped. It was a little bit after the main core of that Soulquarian neo-soul era and leading into a more pop R&B space.

Absolutely. I think had I come out earlier or later it probably wouldn't have had the same impact. But I think at that moment it was absolutely perfect. People were waiting for something new, something refreshing, something edgy. I think the hold-up from Uptown and all those labels (I had) for ten years was just God's timing. It all just kind of created a lane for me. I had [also] just started wearing a trucker hat and flannel shirts when this all happened.

Anthony Hamilton - Comin' From Where I'm From (Official HD Video)youtu.be

How did you start wearing the trucker hats and flannels?

When I did the song with Nappy Roots, “Po’ Folks.” I was flying from LA going to Kentucky to do the video. I thought Kentucky was going to be hot. I got there, and it was freezing. So there was this little store in Lexington and I put on every shirt they had cuz I only had a jean jacket. Then I saw a trucker hat. I put it on and that's what I wore in the video man with a toothpick. Then the song became big and people started noticing. I never took the trucker hat off. I was like, “If this is what people notice and how they recognize me, I'm keeping it. It feels organic.”

Do you feel like you get credit for being a part of starting that trend in the early 2000s?

I think the people in the streets really digging the music and vibe (gave me credit). They were like, “Yo, I like that man. That's the struggle.” I cut off my beard one time and cats were mad at me like, “Man, why’d you cut the struggle off?” It was representing something bigger. So I just left it. I'm the neighborhood raggedy beard man.

Let’s talk about putting “Mama Knew Love” together and using all of the different types of imagery you did in the lyrics.

It's a story about coming through the struggle with pride. I wanted to represent my mom and my grandmother and the people I saw working, back bent, cleaning floors for everybody else. People know those people, those images so well, because everybody knew a grandmother who had high blood pressure or was a little overweight, who stood on her feet all day. People know the spirit behind that. Bills on the bed sitting there waiting to be stared at. Coming home with work clothes on. I didn't want to talk about stuff that was too shiny. Sometimes the things that are the most textured, the most faded out shirt and pair of jeans, are the most beautiful. Those images meant a lot to me because they taught me to have gratitude. I wanted people to feel that it was okay to embrace that. Everything doesn't have to work out all the time for you to have appreciation.

That message is furthered on the title track. Can you talk about how you captured the essence of the struggle there?

I think I captured it because I believed it. I think being someone who was okay with being vulnerable, and exposing things that I've been through, and making people reconnect with things that they probably tried to forget, was healing in a way. So I think that having that type of moment on our album was bigger than just a hit record; it was more like, “This is something I need. This is food.”

There’s a food-centered song on the album that really connected in “Cornbread, Fish, and Collard Greens.” How do you reflect on that one?

“Cornbread, Fish and Collard Greens,” those are the things that represent, like the blackest meal. And when James Poyser was playing that bassline it just felt like a fish fry cookout. My co-writer, Deirdra Artist was like, “This sounds like it’s got cornbread in it, cornbread and fish.” Then I said, “And collard greens!” Then we sang it back and forth. Then I was like, “I'm a pimp. Yeah.” Because that's like money. We took an angle, like, “I'm not pimping women. I'm pimping this goodness.” I wanted it to represent having it all, and part of having it all is this complete meal.

On the album, it also seemed very intentional to show the full spectrum of relationships. From pure love on “Since I Seen’t You,” to deep heartbreak on “I’m A Mess,” to diving headfirst into lust on “Float.” Was that a conscious choice?

A relationship is not one-way. In the duration of a relationship, there are moments when you first meet a person and you lay eyes on them and it's like, “Oh my god, this is an angel.” And then you make love, you have sex, connect through passion and float away. Find yourself living through bliss. Then you get to a place where maybe it's not working out, and then you find yourself being a mess and singing at 4 a.m. up in New Rochelle with Ced Solo (Cedric Soloman, producer of “I’m A Mess”). He met me in New Rochelle one night when I came up from Harlem to the studio. I got there at like 12 a.m. By 4 a.m. the song was so heavy and Ced was laying on that organ. I was like, “I'm either gonna cry or jump out the window.” I chose to cry. I was shut down and I had to figure it out. That song was how I felt. I felt like I was in a blender. I'd never felt that in my life. I ended up losing weight, like 23 pounds.

Nappy Roots - Po' Folks (w/ Anthony Hamilton) [Official Video]youtu.be

How would you describe the balance all the different producers created on the project?

Mark Batson was the maestro, the musical innovator. He was the daredevil creating sounds on his own coming from a wild place. He tailor-made the sounds for “Charlene.” To this day it's hard for my band and certain people to recreate the sounds because the guy is such a wizard. James Poyser is just Juilliard in his head. He understood music in a way to create something beautiful and make it as church as I needed it to be. And also him being Jamaican. He put a little stank, a little plantain on “Cornbread, Fish, and Collard Greens.” Musical gumbo potluck. JD threw in some samples of old stuff that y'all love already. Mark created the broth. James added the andouille sausage and mustard greens. Then Ced Solo brought praise and worship. Then I produced, “My First Love,” “Better Days,” “Chyna Black,” and “Lucille” at Cherokee Studios in LA with David Balfour, Tyler Coombs, and Eric Coombs. We were creating music from a really nostalgic place. Tyler Coombs was more of a pocket drummer like Questlove and he gave me that raw edge that I needed. His brother Tyler played bass so they had chemistry together. Balfour made the album feel really old-school.

So let’s talk about “Charlene.” Did you know it was a hit?

I didn't know it was a hit. I knew it felt good. When we started writing it, Mark had some melodies. Then when it came to the hook, this name Charlene pops up in my head. I'm like, “I don't know no damn Charlene.” But there's a woman I sing about in “Charlene” that I know. But it just stuck with me, man. I was like, “Why would I even choose the name Charlene out of all the names? Not Angie, not Pam, not Keisha?” I think a lot of hit records have names that become personal. I think people can put a face to it, and it sounds like somebody they know. I saw Anthony Hamilton and Charlene together like I knew them. It felt that real.

What do people get right about the story and what do people misinterpret?

People get that “Charlene” did me wrong. And people misinterpret that even though she was breaking my heart, I was still in love with her. Maybe I was also choosing music and pulling away and her best defense was to shut down. That song is about a relationship but there were two ships that began to sail in two opposite directions. Maybe subconsciously, I was choosing to leave and she felt that. I don't think people really get that, but that was something that I was going through.

Is that Anthony Hamilton from 20 years later talking or Anthony Hamilton creating “Charlene” in that moment?

In that moment, I didn't know. I was like, “Oh, my God she's trying to kill me. She's trying to rip my heart out.” Now being aware of where I was and looking back I’m like “This is what probably ultimately caused the breakup.” Hindsight is 20/20.

Anthony Hamilton - Charlene (Official HD Video)youtu.be

How do you feel the album informed the rest of your career and how you moved?

A lot of people at the label didn't expect for it to be successful. And when it did, it kind of gave me the okay to shut them out again. Continue to write songs and tell stories and connect with real emotion. It made me more determined to stand my ground and to continue to work with the people who I knew believed in it. It gave me true fans. Without all of them, I might still be on the shelf somewhere.

Do you believe it's a timeless body of work? And if so what specifically makes it one?

It's absolutely timeless because it was raw, and something unspoken that connects to people in a way that works something up in them. That made them not only love it back in 2003, but continue to love it 20 years later. Even Drake hit me up and was like, “Comin From Where I'm From is one of my favorite albums of all time.” Not only did it touch everyday people, but entertainers and musicians too.

You've talked about how much your debut was needed in music. Do you feel like its energy still exists within R&B today?

It's missing a lot. But there's been some of the younger generation who have sampled it. So people know it's something that's a classic. But I don't think the average listener is ready to hear a new version of it yet. Maybe in a couple of years. And that's okay because I'm still able to go out and do it. Things are so different now, I don't know if it could live in this space had it been born today, and that's okay. So I'll just have the only version of it and keep it sacred. Until we meet again, you know, till we meet that sound again.