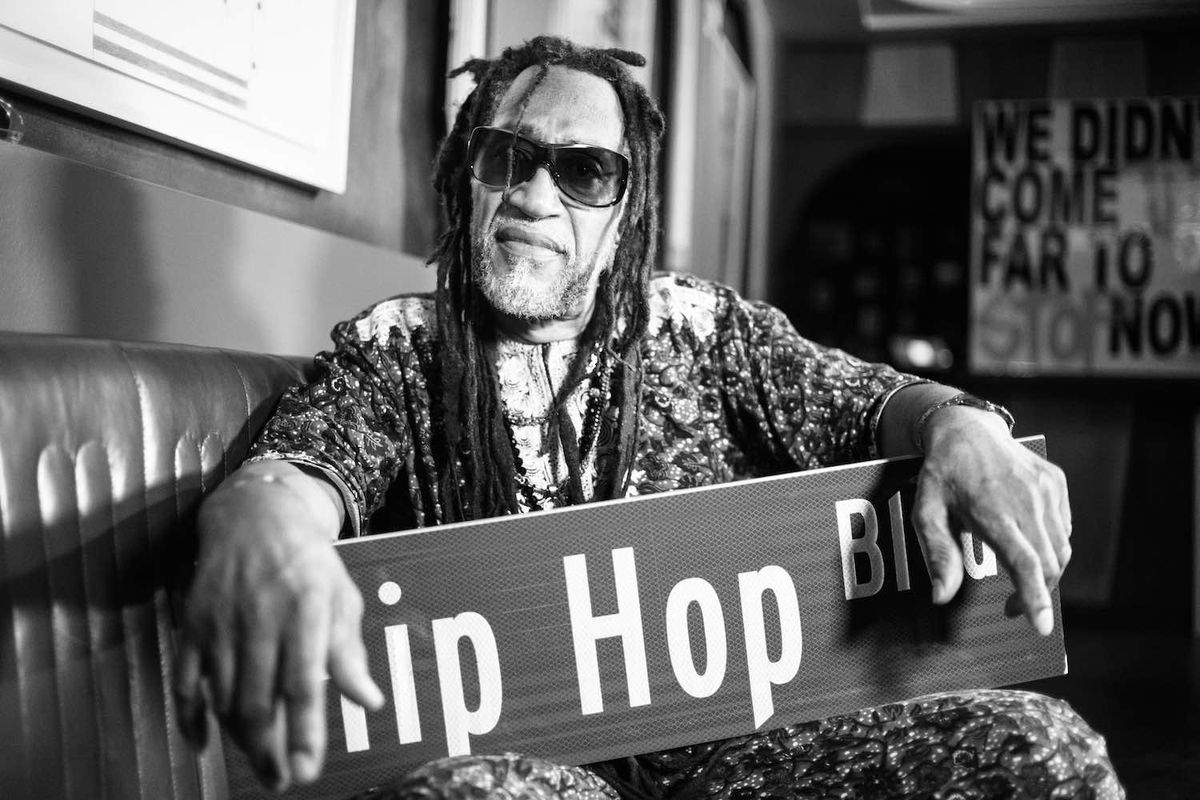

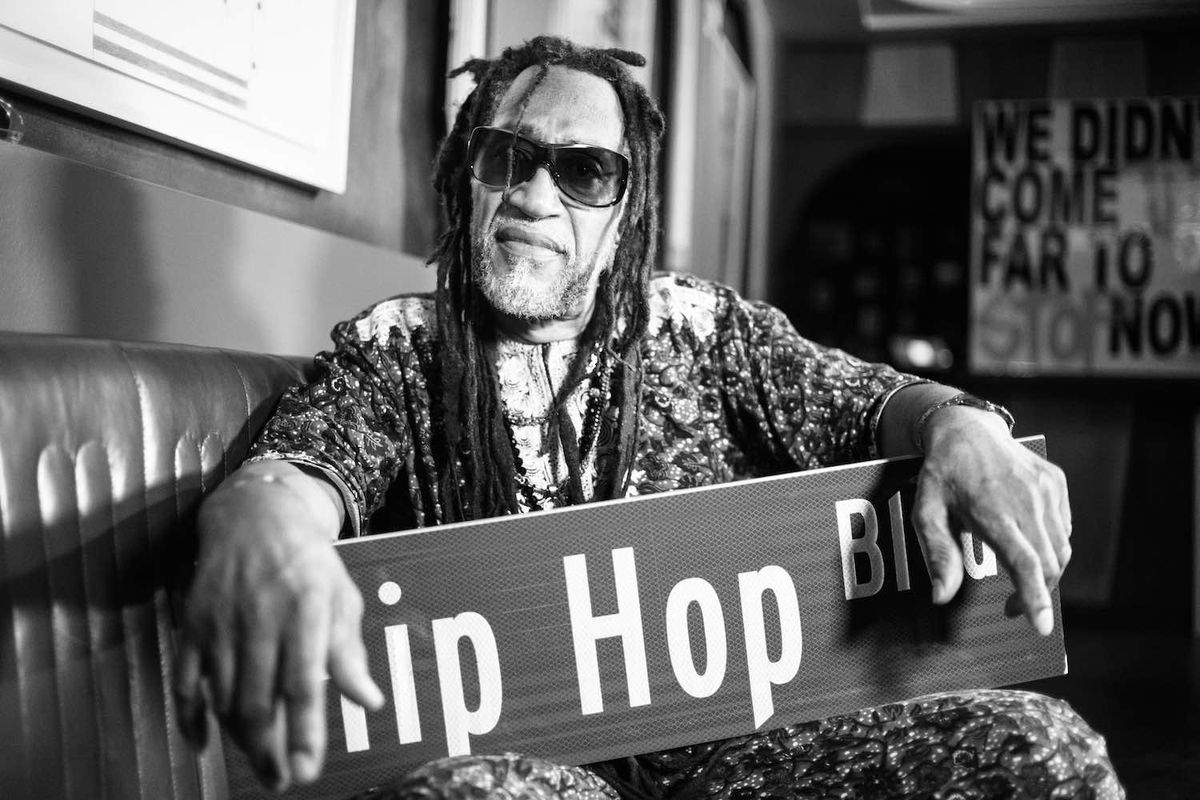

Kool Herc attends The Source Magazine's 360 Icons Awards Dinner at the Red Rooster on August 16, 2019 in Harlem, New York City.

Photo by Steven Ferdman/Getty Images

Kool Herc attends The Source Magazine's 360 Icons Awards Dinner at the Red Rooster on August 16, 2019 in Harlem, New York City.

The story of hip-hop’s birthday on August 11, 1973 is an amazing one. But…is it true?

This article has been handpicked to be included in our Hip Hop 50 collection as a noteworthy inclusion to the genre's rich and diverse narrative.

On Friday, August 11, 2023, anyone sufficiently enraptured by rap music and/or its associated forms — writing (aerosol art), b-boying (breakdancing), and DJing — will, as if on a hair trigger, declare what happened exactly half-a-century ago: hip-hop was born. Or, said another way, on that day Jamaican expat Clive Campbell godfathered it, performing break-based turntable music in public for the first time as DJ Kool Herc, for his sister Cindy’s back-to-school party in the community room of their 1520 Sedgwick Avenue apartment building home in the Bronx.

It was a radical musical act, akin to an earlier one in physics. Like an anti-Oppenheimer, a then 18-year-old Herc formed two critical masses by pulling one apart. This atypical gesture required going back and forth between two identical discs on two identical record players. Doing so extended the “break” — the chewy center of a bass-snare-and-timbale-rich record — and unlocked the core formula of what would change the world as hip-hop.

Further aided that night by syncopated delicacies from his key emcee Coke La Rock, the duo laid down the fundamental rapper-over-music paradigm that has since made vocalists like JAY-Z, Eminem, and Drake multi-multi-millionaires and cultural paragons. In short, Herc’s incipient act ultimately gave hip-hop life, then license. The cachet to cross the borders of every nation on the planet, including ones English itself, has barely broached.

As an origin myth, you’d need to rummage through the MCU’s best to top it. It’s got real underdogs in a battle none would have thought they would wage, let alone win; loads of actual villains; and, despite multitudinous setbacks, a global, celebratory conclusion. If all the ongoing “Hip-Hop at 50” concerts, news coverage, and sober reflections came with confetti, we’d be cleaning it up for weeks.

It is an amazing story. It’s inspired this writer for decades. But…is it true?

The following is not so obvious now because we’re so used to it. However, when you really think about it, the idea of taking the middle part out of a record and just playing that section over and over — particularly in front of a live, paying audience — is kind of weird.

You wouldn’t do that with a movie, TV show, or poem, even today. You wouldn’t even do it with a musical concert. But according to the origin myth, that’s what Kool Herc did on August 11, 1973, thus inventing hip-hop.

What good reasons do we have to think this actually took place? Well, no one's ever put forward a more satisfactory narrative. The story is useful, and compactly describes how the important roles in hip-hop performance (DJ, rapper, dancer) came to be. As a result, the story makes sense and seems to correlate with historical developments — musical, technological, social, and otherwise — taking place at that time.

There’s also the fact that so many people who have deep roots in hip-hop also hold this origin story to be true, and have for a very long time.

“All the great DJs were directly influenced by something that Herc did very early,” said Jay Quan, a hip-hop journalist, historian, and lecturer. “Now, was he the first? I don’t know. But he was the one that everybody saw. Flash never said that he saw anybody else do it. He said he saw Herc do it.”

“The young Sha-Rocks, the Melle-Mels, the Scorpios, all those from the Bronx was goin’ to Herc parties,” legendary promoter and historian Van Silk added. “He was anointed.” The same sentiment is held by many other very early hip-hop pioneers of the pre-vinyl era.

Lastly, we appear to have documentary evidence in the form of the widely-circulated “A DJ Kool Herc Party” invite, which many believe was given out in advance of the event.

Given all of this, what, if any, are good reasons to think the origin myth is untrue, or at least flawed?

Well, for one, there seem to be few people who’ve said they were there that night. Where are the people today who attended the August 11 party? There don’t seem to be many, if any, and even Van Silk agreed: “There’s nobody in hip-hop, in its current space today, who was there.”

Also, writers (aerosol artists) — purveying hip-hop’s fourth element — were doing pieces on trains years before August 11, 1973. Herc was a would-be artist and b-boy before he became a DJ. I went to elementary school in NYC and remember seeing pieces on the outside of elevated trains in 1970. If writers are part of hip-hop (let alone b-boys), how could Herc be father to something that precedes him?

But perhaps the most notable point — one that really speaks to this complicated origin story — is that the widely-shared invite card that has become so synonymous with this party, doesn’t actually exist. It always seemed a little too complete, a little too perfect, though I ultimately accepted it for what it seemingly wasn’t. In August 2022, Christie’s Auction House sold a number of Herc’s possessions, bringing in over $850,000. The sale included a few 1975 notecards. However, the ubiquitous “A DJ Kool Herc Party” notecard wasn’t included, with Christie’s deeming it “an artistic recreation.” Per an article in Forbes, Cindy Campbell also clarified the notecard wasn’t real, and “attested that the flier strewn over the internet purported as an actual August 11, 1973 invitation does not exist.”

In other words, it’s a retro-facsimile with its own complicated backstory (if you want to read more about this object, a recent essay in Perfect Sound Forever outlines its knotty history). According to Van Silk, Herc told him by phone the card was created to launch the extortionate Sedgwick & Cedar clothing line just a few years back. Silk also shared something that, perhaps, highlights at least one temporal error of that notecard, too — that Herc hadn’t met Clark Kent (“Klark K”), one of his DJs, until two years later in 1975. And yet, the invite mentions Kent as a special guest.

Also, these promotional cards were hand-written one at a time by Cindy, as noted in the Forbes article. So, when one sees the authentic auctioned ones from 1974, the handwriting is simple, clear, and expeditious, presumably because whatever one writes must be repeated over and over, in order to make as many handouts as possible. But that’s in stark contrast to the card we’ve all come to associate with the party, above.

In other words, the first problem is we must believe Herc’s invite designs got far less graphically sophisticated from 1973 to 1974. That’s not how designers typically work. Then, because these were handwritten one at a time, this would preclude making a card with, for example, the complicated shadow detail in the August 11 card’s headline text, the “SCHOOL’S STILL OUT” inset, and/or even the blocky “PLACE, DATE, TIME” font. The entire layout would form a huge time-waster when doing it one card at a time. Like trying to render fine fleur-de-lis patterns in the sand. This all supports the following hypothesis: the card was designed to look old and authentic but it isn’t. It was never handed out, and was only drawn once — for the internet.

Lastly, Herc was not the first DJ to play breaks. This is, perhaps, the most complicated part of these objections, particularly for those of us who were not there. Basically, Herc learned to DJ from working with his dad (who also deejayed); from his own desire, drive, and hard work; and from attending jams in the area at long-gone clubs like the Puzzle, Rat Hole, Plaza Tunnel, and more.

In a 2015 interview with the late Reggie “Combat Jack” Ossé, Herc admitted first hearing Jimmy Castor Bunch’s “It’s Just Begun” when DJ John Brown played it at the Plaza Tunnel. He learned of The Whole Darn Family’s sinuous “Seven Minutes of Funk” at a party he attended, upon which he went right up to the DJ and asked him for the track info (a direct tactic Herc’s own scrubbed-off record labels would have certified a major fail).

The Whole Darn Family - Seven Minutes of Funkwww.youtube.com

This was an era dominated by disco and by renowned DJs: Disco King Mario, Smokey and the Smokatrons, Pete DJ Jones, King Charles, Grandmaster Flowers, Master D, Vaughn K, Brown and more. None of these DJs would acquire the legendary and global renown Herc ultimately did, but many would make a profound impression on him. All had their devotees and specialties, and all were trying new techniques, kinds of equipment, and types of records.

In other words, Herc came of age in a rich, fairly mature, and highly influential Black disco subculture, and drew from a buffet of possible approaches. Gifted and dogged researchers are still teasing out the neural pathways of what he saw, but what we can best say is it was profoundly nonlinear. Tentatively, what may ultimately become clear is Herc observed everything he performed in some other setting — including funk breaks and repetition — but not necessarily in one place. Most of all, none of what he saw was aimed at a teenage audience eager to be beguiled, and for whom every aural delight was new. Herc filled this void.

So, with all of this, was hip-hop born on August 11, 1973? Is Kool Herc the godfather of hip-hop? The answer depends on who one, additionally, considers the father and mother of hip-hop and, even more, what one considers hip-hop. As one-time Enjoy Records artist Kool Kyle the Original Starchild told me: “When I started on the microphone it wasn’t called hip-hop, because ‘hip-hop’ didn’t exist back then. They were just ‘parties.’ They were ‘the jam.’” So, even the framing of the question can be non-neutral and impose a bias.

Rather than saying hip-hop was born, I prefer to say hip-hop cohered. This is the result of multitudinous actors working over time and laying in details that form a profound mosaic — work which continues now and into the foreseeable future. Hip-hop will decohere when that work ceases and/or when the work which has been done is no longer observed, studied, exchanged, maintained, or valued.

In the words of musicologist Joe Schloss: “People’s definitions of hip-hop are generally expressions of what they personally find meaningful or valuable about hip-hop culture. And, because of that, rather than get down in the dirt about the different arguments, I try to take the attitude of, ‘It’s beautiful that — after 50 years — people are still so passionate, about hip-hop and what it means to them, that they’re bothering to argue about it in the first place.”

—

Harry Allen, Hip-Hop Activist & Media Assassin, has covered rap music & its associated forms for over 35 years. He hosts and produces the GRR: Global Race Report podcast, and runs harbanger, a turntablist septet, under HARD: Harry Allen R&D, a boutique for developing “singular and outrageous” projects. Allen is a 2017 Nasir Jones Hip-Hop Fellow at Harvard University. He is also a 2020 CAST (Center for Arts, Science, and Technology) Visiting Artist at M.I.T.

Special thanks to Davey D, Kyra Gaunt, Grandmixer DXT, Loren Kajikawa, Mark Katz, Pete Nash and Gregor Scott for their excellent counsel, ideas and insights. Happy August 11th!