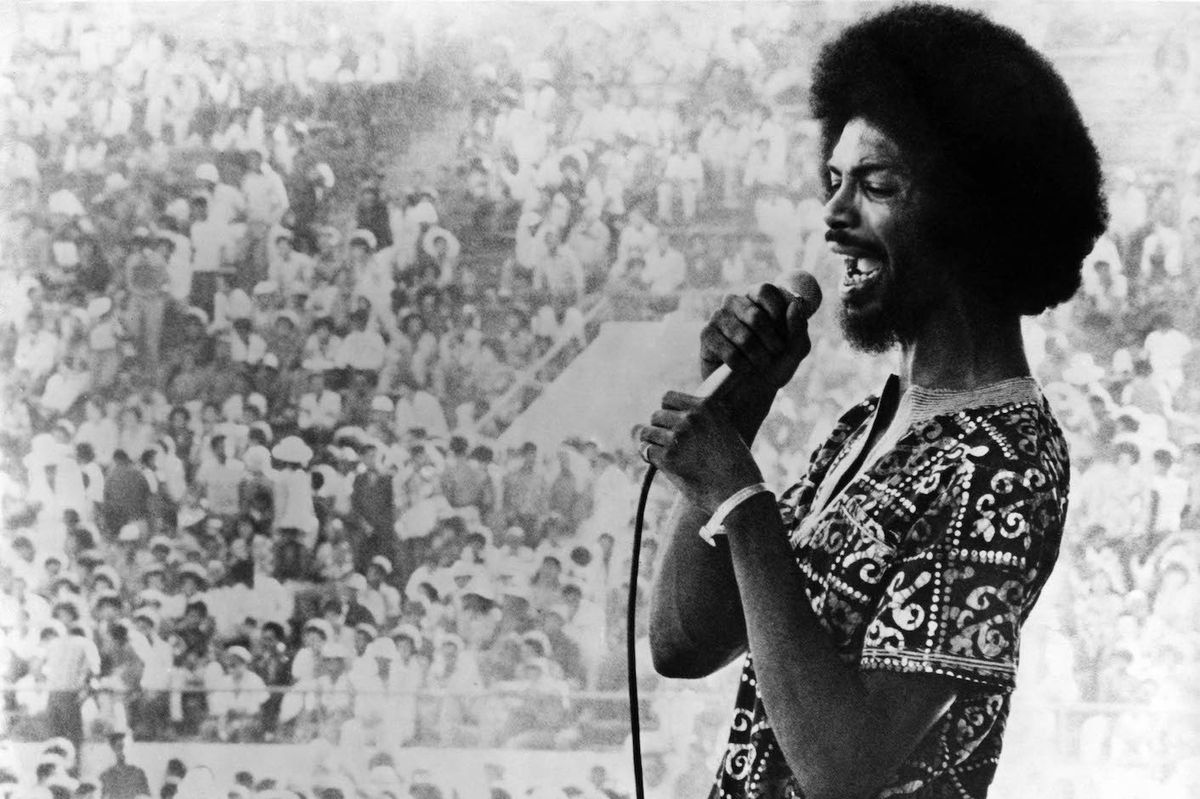

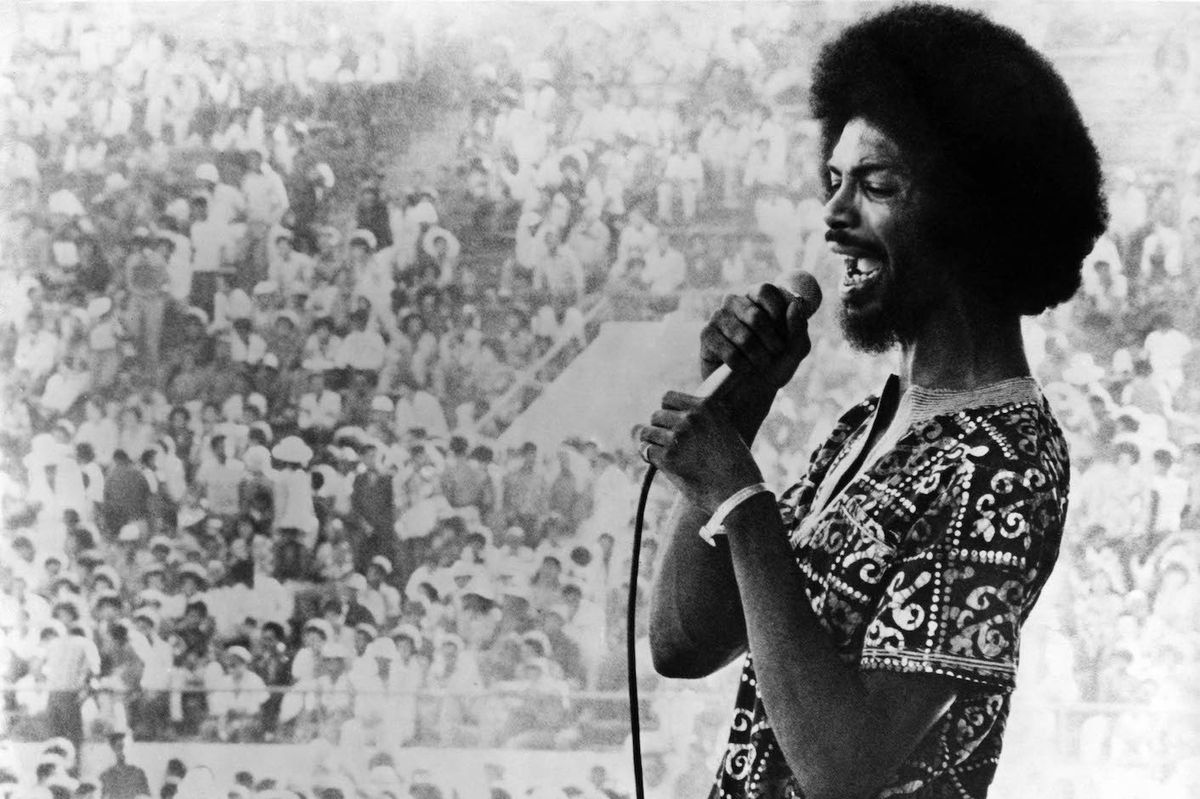

Gil Scott Heron performing on stage.

Photo by Echoes for Redferns via Getty Images.

Gil Scott Heron performing on stage.

This article has been handpicked from the Okayplayer editorial archives and included in our Hip Hop 50 collection as a noteworthy inclusion to the genre's rich and diverse narrative. The article has been edited for context to ensure its accuracy and relevance.

Gil Scott-Heron’s recording journey begins in Chester County, Pennsylvania at Lincoln University in 1969. Following in the footsteps of his idol Langston Hughes, Scott-Heron made the decision to attend the famous HBCU. Here, he would meet his long-time collaborator, Brian Jackson, and begin crafting socially and politically conscious and Afrocentric material that solidified the two as a prolific duo for the next decade. Within the same year, Scott-Heron took a leave of absence from college life to focus on writing two novels, The Vulture and The Nigger Factory. A year later, The Vulture was published, and he launched his recording career.

Upon receiving production assistance from legendary producer, Bob Thiele, Scott-Heron released his debut album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, on Flying Dutchman Records. The songs gave an insightful glimpse into the harsh realities that America, and in particular Black America, was facing at the start of the 1970s, as well as introducing the world to Scott-Heron’s spellbinding baritone voice. Due to the unexpected success of Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, Scott-Heron was given the opportunity to release his second album, Pieces of a Man. This would be the first time Brian Jackson featured prominently as a collaborator. His next album, Free Will, was released in the late summer of 1972, and it was the last studio album he recorded for Flying Dutchman Records.

During this juncture, Scott-Heron finished his Master’s Degree from John Hopkins University and began teaching at Federal City College [now The University of the District of Columbia] in Washington, DC. As he and Jackson began their search for a new studio to record in, their creative compass led them to a studio, not far from Howard University’s campus, in Silver Spring, Maryland. While Scott-Heron was teaching, he continued recording fresh music with Jackson. Their next recording effort proved to be their most successful work to date.

After a dispute with Flying Dutchman Records, Scott-Heron left for the artist-friendly label Strata-East Records in 1973. Shortly thereafter, Winter in America was released in May 1974 by Strata-East Records. It was the first album to feature Brian Jackson’s name on the album cover. The lead and only single, “The Bottle,” propelled the tandem to achieve unknown commercial success. Along with his previous offerings, this album showcased an eclectic mixture of blues, jazz, and soul music. “The Bottle” would peak at #15 on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart and #6 on the Billboard Jazz Albums Chart. As a result, this entire album was given the distinction of being one of the first rap albums in the history of music, alongside the works of The Watts Prophets and The Last Poets.

To get better insight into this classic, we spoke with Brian Jackson about the intricacies behind its construction.

When and where did you first meet Gil Scott-Heron?

Brian Jackson: I met Gil in 1969. It was my freshman year at Lincoln University. I had been sorely disappointed by the curriculum which I had anticipated to be way more Afrocentric than it was at the university. It was an HBCU. I found out that I was being taught “the classics” without any reference to any American classical musicians such as: Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Count Basie, or any creative, great composers, even Scott Joplin. Also, none of the writers like Countee Cullen or Langston Hughes or W.E.B. Du Bois or any of the writers and people who helped shape American culture and American literature, Ralph Ellison or Richard Wright or anybody. We were looking for somebody.

Being in a black university, I thought that should’ve been happening. Kwame Nkrumah went there. Thurgood Marshall went there. Oscar Brown, Jr. went there.

I was sorely disappointed by all of that and ended up spending most of my time in the piano practice room. It just so happened that one day I was in there and a young student, well, not as young as me, he was a junior, came in and asked me if I wanted to be part of a talent show. I said, “Yes. If it involves playing music, I’m down.” He was doing a song called 'God Bless the Child.' He was looking for somebody to do it in the arrangement of the ‘Blood, Sweat and Tears’ version. I knew that arrangement, so I was on. Then, it came to be that he was going to do two songs.

The other song that he was going to do was a song called “Where Can a Man Find Peace”. He wanted to introduce me to the writer of that piece and it happened to be Gil. We just hit it off from there and decided that I had the tunes and he had the lyrics. It was a no-brainer. We began to write constantly and consistently and put together a band. I think it was 10 pieces. We had five singers, a flute player, a drummer, and a bass player. We called ourselves Black & Blues. [Laughs] That was the precursor to The Midnight Band.

When you started working on the first record together, what was your vision for it? Was it more of Gil’s vision or was it a partnership?

Yes, when we were writing, as Gil would have you know, the music always came first. Then the music dictated the feel of the lyrics and the tone of the message. What we knew was that we wanted to write good songs. That was number one. Number two, we didn’t want to write songs that anybody else would write. I didn’t say could write, but would write. What we saw were people writing songs about unrelated love, unrequited love, and trying to get in somebody’s pants. There were plenty of songs like that. We saw that we couldn’t really add much to that dialogue and conversation.

We looked elsewhere, and what we came up with was the fact that we were young black men living in America, which was a frustrating and frightening experience. We did what we knew best. We decided that we would write about that. We were lucky to have been able to do that first album, because originally, Bob Thiele, the head of Flying Dutchman Records, was basically interested in spoken word. It was cheap and plentiful.

He was able to get people such as journalists Pete Hamill and Carl Rowan to speak on record and to have music sometimes behind them or not. Pete Hamill’s Massacre at My Lai was a classic. He was looking for Gil to do the same thing reciting his poetry. It was Gil’s idea to take it in the direction of The Last Poets, who we were enraptured by. It pointed the way toward what we felt could happen in black poetry and in music. So — he did Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. Instead of just having and reciting his poetry, he did it to the beats of African drumming.

While all that was happening, we were writing tunes left and right every day. We would sit down and compose. We had quite a stockpile of material, and we thought it would really be nice if we could record some of that stuff, too. He went to Bob Thiele, and he asked him if he could do something like that. Bob said, “Well, that’s another level of recording. I’m not sure. Let me say this to be fair. If your poetry album does okay, then I’ll take a listen to what you guys have written.” We went up to his office, and we played a few songs for him like “Pieces of a Man,” “I Think I’ll Call It Morning,” “The Prisoner,” and I think we played “A Toast to the People”. He asked, “Okay, so who do you want on the album?” That was the beginning and we went from there. That would’ve been our first album, Pieces of a Man. He hired Ron Carter, Bernard Purdie, and Hubert Laws. I was able to bring in my high school buddy, Burt Jones, who ended up playing on Saturday Night Live. As a young teenager, he was already playing in bands with Wilson Pickett.

We met again in college. It was a weird story because we used to ride the bus every day to high school in Brooklyn. In high school, neither one of us had any idea that we were musicians. I just happened to run into him on the campus of Lincoln University playing guitar and leading a band. I told him, “Man, I never knew you played guitar.” He replied, “I never knew you played piano.”

You guys started out on Flying Dutchman, but recorded at RCA?

That’s right. We recorded at RCA Studios on 1850 Broadway in New York City. It was dubbed “the studio.” That was history. You could feel the vibration in the walls of all the great musicians who had recorded there. I’m sure John Coltrane recorded in that room. It certainly felt like it. It was a huge empty space and could be configured in any type or different ways with the movable walls and stuff that they had in there. You could have put a whole orchestra in there, if necessary.

But with the Winter in America, you moved to Strata-East. What was that process like?

What happened was that the contract ran out. With Flying Dutchman, we had a three-record contract. By the time we had done Pieces of a Man, a lot of the older musicians had started pulling our coats talking about publishing because Bob Thiele wasn’t giving up any publishing. Understandably so in a sense, because he had a small label. He wasn’t really making any money off record sales. The problem that we had was he was taking all the publishing. He took one-hundred percent of the publishing. Here we were, busting our asses to do this, to write these songs, and we weren’t even getting a bit of the publishing.It had been drummed into our heads by the old guys that we knew. The old brothers would tell us, “Look here. Publishing is what’s going to keep you going when times are hard. Get that publishing check and believe me, you will be glad that you didn’t give away all of it.” They had drummed that into our heads so much, by the time we finished Pieces of a Man and were thinking about doing that third album, we were already upset by the fact that we were feeling like we had got ripped off, even though it was our opportunity and a lot of our artists have experienced that when they were starting out. Newbies in the business gave away their publishing just so they could get their foot in the door. We didn’t feel comfortable with that. Bob was happy with us, but when the time came for us to renew, the first thing that we wanted to change about the arrangement was that we wanted to get our publishing. Bob wasn’t really down with that at all. So we left, and we basically saw what he did, and we felt like we could do that, too: He sat in the control room and smoked a pipe and would tell a guy, “Yes, right there. Mute that. Raise the volume on that, more bass, whatever.”

It was simplistic. But we didn’t really see all the other aspects of it. One of the biggest aspects was, how do you get musicians? You’ve got to pay musicians too and studio time. We had to find musicians and pay them, but we didn’t have enough for that. We had enough to hire a studio, but we didn’t have enough to pay musicians and bring them there. The only musicians we really knew were guys from Lincoln. We decided it was probably best that we just do it ourselves. Hey, this was the ‘70s, we could overdub. So, overdub we did. That’s one of the reasons why Winter in America is so sparse is because we figured it was safe to do it ourselves. It was less expensive. Some of our buddies came down anyway to help out. On songs like: “The Bottle,” “Rivers of My Fathers,” and “Back Home,” they came in and added bass and drums. Danny Bowen was on bass and Bob Adams was on drums, and it all helped to round out the album.

What made you and Gil want to move to D&B Sound in Silver Spring, MD versus the bigger studio that you were recording out of in New York for the previous albums?

Money. We only had $4,000. [Laughs] Man, we had to make it stretch. We couldn’t afford 16 tracks so we went with eight. We found this brother named Jose Williams, who was not only just an engineer, but he was like our uncle. He helped to guide us and teach us the ropes. He saw something in us, and he worked with us. He was more than just an engineer. He was like another brain, another part of the production, and part of the production team. It was under his tutelage that we learned more about making records. We were just lucky.

When I got kicked out of college, I moved back to New York, which was uncomfortable living with my parents. When Gil ended up getting a chance to teach and earn his master’s degree at John Hopkins University, I moved down to D.C., so we could be close enough to take a stab at writing some more material. During that time, we took a trip down to D.C. to do a gig. Bob [Thiele] had arranged a gig with us and Stanley Clarke, Pablo Landrum, and Bernard Purdie. It was a gig at Howard University. It just so happened to be around cherry blossoms season, and between the cherry blossoms and the chocolate women that we saw, we decided that this was probably a better bet than Baltimore [laughs].

Was the budget why the album was recorded over the course of three or four days?

Oh, yes. That would definitely explain it. Not only that, but it was simple for us because we were playing these songs all the time at home. There was very little overdubbing. For instance, a song like “Your Daddy Loves You,” even though there wasn’t a dedicated vocal booth, Jose had a closet that was lined with cork. So, he used to put me in there with the water fountain and I played the flute along with Gil, while he was doing his playing and doing his vocal. He would cut the reference vocal, so there we would have the whole track, then we would switch.

He would go into the closet and do the vocals, and I would redo the piano and that’s pretty much how it came together. It didn’t take a lot of the time. We were knocking out three or four songs a day. We had rehearsed it and practiced it so much that we basically knew what we were doing. At the point when Danny [Bowen] and Bob [Adams] came down, we just threw them on there, and they were also familiar with the material. When they came down, it was just quick and easy.

What was your regular studio routine during this album?

Not too early. [Laughs] We would usually start like early afternoon, and Jose was a family man, so we wouldn’t be staying around all night long. He had to get home, and we respected that. So, we kept pretty sane hours. We would spend eight, nine, 10 hours in there max, which gave us enough time, and Jose was no nonsense. We weren’t sitting around BS’ing and carrying on. We were in there cutting and listening and deciding and moving on, and I could keep going back to that figure of $4,000 because it was not a lot. When you look at that $4,000, you also must look at the fact that we had done more songs than were on the album. Eventually, we had to re-cut a couple of the tunes that ended up on the album. We had a new vibe to it. Yes, there were a couple of little things we had to take into consideration and the fact that we had to mix it as well. Jose was not a person to second guess himself. He knew his studio. He had built that studio by himself, and he knew everything it could do.

He had a Fender Rhodes piano, an acoustic piano, and I would have to say that the Fender Rhodes changed my life. It was a beautiful Fender Rhodes. It was gorgeous, and even at one point, we had rented a Fender Rhodes bass piano. It’s a smaller version of the Fender Rhodes but with only the bass keys. Donny Hathaway used to play that. Now, thinking about it, he was down in D.C. at that time. Maybe he had played that one. Who knows? Anyway, yes, we had used that in a couple of tracks. We weren’t crazy about it, and so, where the bass parts were, we replaced it with an actual bass.

By that time, I had clearly decided that the Fender Rhodes had to be a part of my musical diet. I was really blessed that there was an extra piano there at RCA Studios and that kind of turned my head around. I have to say from that point on, there was no turning back as far as I was concerned. Even though I ended up recording on the Farfisa electrical piano, it was only because I was afraid. I didn’t want to be a copycat. I didn’t want to be seen as someone who was trying to copy the sounds of some of the great pianists that I admired most like Herbie [Hancock], Chick [Corea], George Duke, and Ahmad Jamal. So, I had a pretty long stint there with the Farfisa electric piano, but in the end, the Fender Rhodes just won out.

What was the first song you guys cut?

I think it might have been “Rivers of My Fathers” because “Peace Go with You, Brother” was a little complex in the sense that we had to put that part on with the beginning “Now more than ever/All the family must stay together.” Not that it was complex, but it was just that it was still kind of brewing in our minds, and we were very anxious to get “Rivers of My Fathers” down. I’m thinking that might have been the first. I know it wasn’t “The Bottle”. “The Bottle” wouldn’t have been the first. When we originally cut it, we had little vignettes between songs where Gil would set-up the whole story about the guy coming home from the war and talk a little bit about what the following song was going to be.

Actually, we cut those first but they never appeared on the release. It was very simple because it would be him talking and some eerie kind of sounds going on. They were very stark, almost a Gregorian chant type with an intervallic piece of electric piano stuff going on behind him, which would come away at the end of the album. What we intended was that the story ended in the realization that the narrator was quite insane and that he was talking to his psychiatrist from inside the mental ward in a hospital. See, I told you it was a little heavy [laughs]. We scrapped it and decided we could just use the best songs that we had. We really wanted to have a musical novel type of thing, but it just wasn’t working.

What was your and Gil’s mindset going into the making of this record?

We were looking to expand our skills as writers because that was primarily what we saw ourselves as -- songwriters. We were looking to expand our skills as songwriters and to try our hand at producing. Like I said, we had this ambitious idea to do something kind of like what we were calling a novel, a musical, a musical novel. That was our main impetus. We didn’t know what we were going to do with it. I’m pretty sure we didn’t have many hopes of having a label pick it up. We were just fortunate. After we completed the album, we found that there was a label that was offering musicians 85% of the gross earnings from the sales of the album, if they would just bring in the product, and Strata-East would do the rest.

It was started by two musicians [Charles Tolliver and Stanley Cowell] who understood the grief and pain of producing an album and not seeing anything from it. That was our mindset. We thought, “Man, we don’t want to get ripped off. We don’t want anybody to take our publishing.” That was a huge thing. We did the math, and we figured that even if we sold a thousand records, we would make more money selling a thousand records than selling 10,000 through a record company, and being paid pennies on the dollar. That was our impetus to maintain control of our own art and our resources.

Were there any interesting behind-the-scenes stories during the making of the record?

An interesting thing about “The Bottle” was that a friend of ours, Tony Green, who I had met while he was playing with Pharoah Sanders in D.C, almost had an accident. I’ll tell you how I met him. We were watching a show in D.C. where Rashaan Roland Kirk and Pharoah were playing. Pharoah, I think was closing, and Tony Green was playing the drums on Pharoah’s set. I was standing off to the side when I saw that Tony’s drum throne kind of unhinged itself and was about to slide off from the top part. Somehow, the cushion part of the throne had dislodged itself, and Tony was almost standing up. I realized that, and I said to myself, “This guy is getting ready to crash to the ground and not in a good way,” because the stage was up high, and he was right at the back of the stage. I just ran up behind him, and I grabbed the seat and I told him, “Just jump up for a second,” and he picked up on what I was doing, and he raised himself up a little bit, and I shoved the seat back up underneath him. That’s how we became friends [laughs].

We hung out a lot. We were hanging out with some of the same people. We would run into each other. So, it just happened that when we were recording Winter in America, he was there. When we were doing “The Bottle,” he was there and we had just gotten Bob [Adams] and Danny [Bowen] to come in and do their parts. Tony and Jose [Williams] were in the studio together, and at the end part when Gil is saying, ‘Look around on any corner/if you see someone looking like a goner/it’s gonna be me,’ we felt like it needed something. Jose and Tony came up with the drum part. I think it’s on the fourth beat, and Tony would hit the tom-tom. It propelled the rhythm forward. He overdubbed that. That was Tony’s contribution, and if you ask him, he would still tell you about that [laughs].

We had a couple of good people around us. They helped to keep us sane and keep us focused, doing something we had never done before and never anticipated having to do, but it was great. A fast food restaurant named Carl’s Jr. was around there. I used to run over to Carl’s Jr., and they used to have these hot fudge sundaes. I used to go over there and get one of those. It was one of the reasons why I used to love to record over there because there was a Carl’s Jr. not too far away from there. I used to go get that hot fudge sundae and run back to the studio and get ready to work for the rest of the night.

Let’s delve into some of the other songs from the record and the making of them.

On “Peace Go with You, Brother,” like I said before, the majority of the time the music came first. When I played that song, Gil asked, “What were you thinking about?” This was our usual methodology. I responded, “Well, it’s about unity, basically. It’s about unity.” He thought about it, and he started writing his lyrics and the lyrics were all about unity, but from a totally different angle. The lyrics were talking about the issues that separate us, rather than just saying, “We need to be together,” which is what the opening dialogue and opening chant are saying, ‘Now, more than ever/all the family must be together.’ That’s already been said, but that came as an afterthought to kind of strengthen the message. The message in “Peace Go with You, Brother” was about how these things, these events and changes in our lives seem to be taking us apart.

When we become better educated, and we have better positions and better stations in life, many of us tended to shy away from the community that we came from, that we rose out of to achieve these successes as professionals. In the second verse, we started talking about how we argue among ourselves so much and that we distance ourselves because we disagree on things, rather than understanding that it is possible to agree to disagree, without destroying the relationship that you have, especially within your family. The last verse states very simply, all your children and my children are going to have to pay for our mistakes someday, so that’s why this song is called “Peace Go with You Brother,” and in parenthesis, it says (As-Salaam-Alaikum) because you know my children or your children will have to pay for our mistakes someday, so when I see you, let peace guide your way.

It’s all about reconciling our differences so that we can move forward, because the only way a successful change can come about is, if we all agree on what that change is. In order for us to agree on what that change is, we have to agree on a lot of other things first.

What about “Your Daddy Loves You?”

“Your Daddy Loves You” was kind of the same thing. What happened was that was a piece from the original “Supernatural Corner” thing. It was tied into how the protagonist had come home from Vietnam and was having mental problems, which caused friction within his relationship with his family and his woman, the mother of his child. I had been playing a lot of flute, obviously, then I started playing the saxophone. I really wanted to play the sax, but I got a saxophone with a really cheap neck strap, and it ended up severing one of the suprascapular nerves in my shoulder to the point that I was no longer able to raise my left arm above my shoulder, and once I realized that, I had to stop hanging things around my neck, which meant I couldn’t play the sax anymore. But I was just getting the fingering of it and everything, and I said to myself, “I’m not giving this up,” so I got a flute. I started getting good at the flute. I was being influenced and inspired by Hubert Laws, so we recorded flute on both of those Flying Dutchman albums. It made me really want to continue because it was a unique sound to have that in our music. That was a typical example of a song that Gil and I could do anywhere by ourselves. There were a couple of songs like that and that was definitely one of them.

Was this song a special one for someone in Gil’s life?

Okay. I’m glad you asked that question. I was just about to bring that up. Because Gil had no children at that time. It would have been maybe another seven, eight years before Gil had a daughter. It was not about anybody in particular. It was in service of the story that we were constructing. The fact that he was able to portray so vividly the feelings of a father in that situation, going through conflict with the child’s mother and being painfully aware of the fact that he may not be there for her at some point because of it, spoke to Gil’s ability to tap into the feelings of people who had been in situations like that.

Situations that he might not have necessarily been in himself at that moment. Same with “The Bottle.” He wasn’t an alcoholic, but he could relate to it. He could relate to the feelings. He could put himself inside of someone else’s shoes. The same with “Home is Where the Hatred Is.” See, he wasn’t a junkie when he wrote that, but he was able to access the anxiety and the shame of having to be seen by people you care about and be judged by people that matter to you, which is why I ended up doing it on my album. Because, at that time, when Gil was having a problem with drugs, it was kind of like my way of saying, “Don’t judge him.”

How about “Song for Bobby Smith” and “Back Home?”

On “Song for Bobby Smith,” I was fooling around playing with the chords and a friend of Gil’s, who had a little boy, came over to visit. We were all sitting around in the living room, when I started playing the song, and as Gil said in the song itself, as he was setting it up, the four-year-old boy was into the whole thing with the instruments and everything. He asked, “What are you doing?” We replied, “We are writing a song.” We played it for him, and he said, “Write this song for me,” and his name was Bobby Smith.

We wrote the song for him, and it was all about promise and hope. When we looked into his eyes, we could see all of that. We could see how he wanted to expand and learn and grow. His enthusiasm for life and creativity just inspired us, and it became “Song for Bobby Smith.”

And “Back Home” was again about the theme of simplicity and innocence and how things were so much simpler. Gil spent a lot of time down South as a young boy. He had some experience with how simple things could be for a young boy in the South, even though it wasn’t necessarily ideal under any circumstances for a young Black boy in the South. But there were a lot of good parts to it, too. There were those days when you could have some type of a treat, or have a pecan pie that your grandma made and sit on the stoop and have a cold lemonade or an ice cream cone or just run around the neighborhood, you know what I mean? Once again, it was all about the contrast between the simplicity of youth and how America was beginning to make even the simplest things complex.

And life itself. I can’t blame it all on America, because when you grow up, life does become more complex, but added to that layer was the whole layer of control, the whole layer of what was happening to all of us through the engineering of consent and mass revenue and Wall Street picking us apart; the government agencies and surveillance and war.

As you look back on the making of this album, what are your feelings about being involved with the making of it and collaborating with your longtime friend?

I feel that it was probably at the time where we had the greatest amount of creative freedom. We were doing this for ourselves and by ourselves. We had a lot of help along the way from people like Tony Green, Jose Williams, and Dan Henderson, who was our manager at the time, and Danny [Bowen] and Bob [Adams] and our friends who listened to it and critiqued it. We had a lot of help along the way, and of course Strata-East, coming along and saving the day by being able to pick it up and distribute it.

Back then, it was impossible to do an album for less than $50,000. People look at that now and say well that’s crazy because I can sit in my house and do an album right now. We were just lucky that we found a solution. We found this brother in Silver Spring, Maryland, who was willing to work with us, who believed in us, and gave everything that he had and the benefit of his experience, to help us follow our dream. So, I have deep respect for Jose Williams, and it was great opportunity for us.

__

Chris Williams is a Virginia-based writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, Red Bull Music Academy, EBONY, and Wax Poetics. Follow the latest and greatest from him on Twitter @iamchriswms.