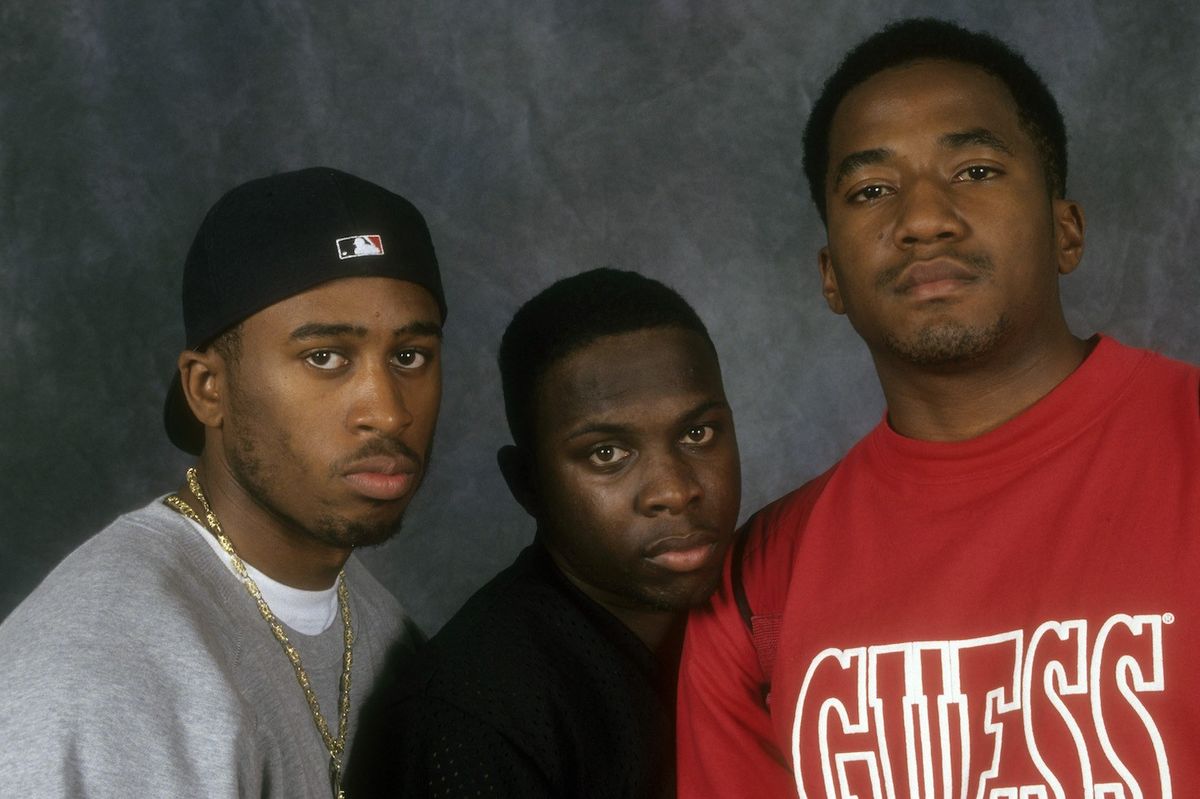

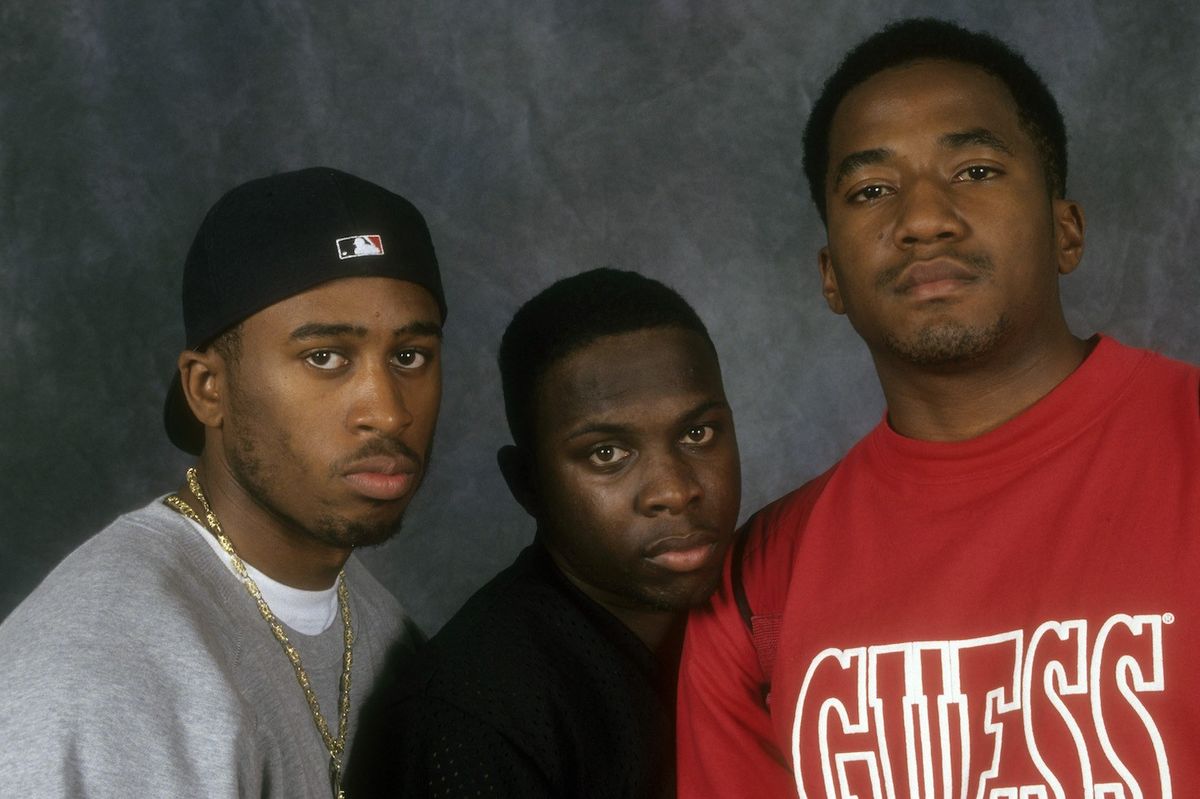

A Tribe called quest the low end theory

Photo Credit: Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In 2016, we talked to engineer Bob Power about the work he did on A Tribe Called Quest’s seminal album The Low End Theory.

This article has been handpicked from the Okayplayer editorial archives and included in our Hip Hop 50 collection as a noteworthy inclusion to the genre's rich and diverse narrative. The article has been edited for context to ensure its accuracy and relevance.

Originally published in September 2016. Interview conducted by Eddie "STATS" Houghton.

A Tribe Called Quest’s classic album The Low End Theory turns 25 today, and Bob Power can’t help but feel like a proud mom — well doula anyway. As the resident engineer at Calliope studios during Low End’s recording, Power was the the sonic midwife in attendance at the birth of one of hip-hop’s most enduring album statements. In fact, considering the pivotal role Power played in a whole host of rap classics — recording with not only Tribe but De La Soul, Black Sheep and Jungle Brothers — it would be tempting to say he was the ultimate fly on the wall for the Native Tongue collective’s greatest period of creativity. But that would be an understatement; Bob Power was the wall — as in wall of sound — providing the ear and technical knowledge to transmute a fertile stack of verses, samples and abstract ideas into a thumping sonic attack that felt like a coherent piece of art.

Getting the chance to hear Power reminisce over The Low End Theory is a special kind of secret history, a journey wherein the landmarks have less to do with the dates of specific sessions or the names of who was in the studio that day, and more to do with moods, sonic signatures and level of funkiness. If you want to know about rap crews and beef, this is not the secret history you are looking for. But read on if you want to learn how the low end was put into the The Low End Theory.

How did you first link with ATCQ or what was your first awareness that you were going to be working on this project?

Bob Power: Well I had been kind of a staff engineer at a place called Calliope and lot of hip-hop crews came through our doors to do their thing. We were open, we were not stuck in the old school. You know, there was a lot of sort of unconscious racism going on in the studios at that time, so — and to be fair, not so much because there were people of color coming in but more because it was 18, 19-year old kids who dressed and talked differently than these people had ever heard before. The studios in New York were fairly integrated for a long time, so the whole jazz age — the jazz way of looking and talking — had been in effect for 30 or 40 years. And then hip hop was a new way — literally — of talking walking, dressing, speaking — so we were very open to it. I met them [Tribe] midway through the first record [People’s Instinctive Travels] and we clicked. I did a couple records off that. There was another guy, a great musician named Shane Faber who mixed a couple of the records…and we just got along. You know the guys are really great people. You know I did a lot of different stuff in the music business, you know I’ve scored TV, I did commercials, lots of different stuff and my mantra is, Make good music with good people. And both were happening here, so that’s really how it started.

It was not a drug crew, it was not a gun crew. None of that bullshit involved. The drugs and alcohol thing, it crosses every genre... I would see other bands sitting in the lounge with a bottle of gin or a 40 and their eyes going cuckoo — and it was great because I didn’t have to deal with any of that. I love to work, I love to make forward motion and make things, and the guys were super focused like that too. It was a lot of fun, too — I mean the weird news is they were 20 years younger than me, and the good news is they were 20 years younger than me. I didn't have a social agenda with guys and that was a good thing. I think Vinia [Mojica] in one interview called me “the den mother.”

In a way I was like an architect or a construction superintendent; I was there to get the work done. And the technical challenges at that point were so huge…you know there was next to no sampling time available, there was 3/4th of a second and a second and a half. Stuff like that, and MIDI stuff — it was the wild west at that point. MIDI interfaces for computers, it was a crapshoot as to whether they were going to work or not, one manufacturer’s synch-tone didn’t talk to another one’s, so I was really concerned with, OK, I see what they’re trying to do and these are both the technical strengths and limitations of the studio…how can we bring those two worlds together. I do know that on the Low End Theory, the guys gave me a lot of room. Part of how I heard that record, which I believe is how it is, is there were elaborate reconstructions…actual, new music was coming out of combinations of samples in ways that people had never done before.

A lot of that had to do with the fact that sampling never was available, and with sequencing and with computers, even if you didn’t have enough memory, say for example for a whole phrase? You could sample the first half then the second half, you know, stuff like that. I had the idea at that time that there were specific musical elements inside of each sample that were what they really meant to be the construction set of the music. So for example if there was a sample with a Rhodes on it, a Fender Rhodes part in it, and I’m like, OK is the important thing the Rhodes? And they'd say, Yeah, so I would try to filter out the other stuff — the kind of things I'd never do now because I love the flavor of all the parts rubbing together.

At that point I was in a really big learning phase as an engineer and I sort of grabbed on to the really remarkable musical ideas that they had, and still you know you listen to that record and it's like, wow all this stuff works together from all these different places. So I was totally fascinated by that and I spent — they allowed me, you know they didn’t give me a hard time about that — I spent a lot of time sort of cleaning things up to make sure they worked together. Again something that I wouldn’t do now necessarily and as well something that was not as relevant to Midnight Marauders, where it would have worked against some of the context of that record.

Ali and Tip both said to me that with Midnight Marauders they wanted it to be much more gritty and street-style; don’t worry about cleaning stuff up, this should sound like Saturday night in the back of a jeep in a crowded neighborhood. So the mindset of the records was a little bit different and I think it's clear if you listen to the records. And the interesting thing is, as quote-unquote street style as Tribe Called Quest may have wanted to get with the music and the concept of the record, it still was you know, friendly. It was not N.W.A. — which in many ways was a fuck you to the world, you know, and I say that in the sense that the sex pistols did the same thing.

Everyone who hears this record comment on the spareness of the sound — when you’re talking about drilling down and getting different instruments to gel together, it strikes me that it’s almost a similar effect to the recording on some of Miles Davis’ fusion records, where trumpet and synth and tabla all kind of gel together —were you consciously going for that?

Yes and no, not in that literal a sense but, you know I have a real background as a musician and I am big believer in something that Miles always said and it is certainly true of funky music, that the notes are defined by the spaces between the notes, you know? A pitch is just a pitch, a note has pitch and duration; you throw it out there, if it doesn’t have relationship to anything else it kinda doesn't mean anything — but in relation to the things around it, including the space around it, all of a sudden it has, you know, either rhythmic or melodic significance. I view mixing and sonics the same way. When you mix a record, there’s two main things that are important: musical balances, which are really important, and timbral or tonal balances. And in order to get the second one right — and actually the first one to some degree, to make room for everybody — it's really good if the tonal and timbral qualities of the different instruments don’t step on each other.

It’s funny I taught a class in arranging today and I was telling the kids that arranging is exactly like mixing; its sort of legislating the levels of the tension of [the musicians]. Something should always be on the primary level, the secondary level and tertiary level. You know this is pop music so the primary level is almost always the vocals. In funky music, generally the drums or the groove is the second level that you want people to perceive as on top, and with rock music it's guitars. So getting all those elements to speak in their own places really necessitates having a little elbow room between ‘em. And with as much mixing as I do the hardest thing about my job is music that's not well arranged. In an old traditional sense it's like oh here's the horn section, the type of line here the type of chord there.

But in the modern sense it's your choice of instruments and sounds are the arrangement. What kind of bass did you use, what kind of bass sound, how does that relate to the kick drum, how much top end and edge is there to the guitars, is that interfering with the vocal; stuff like that. With people who know what they are doing it's like walking out and being in harmony with nature, but a lot of times people aren't that good and even I know as a producer sometimes you're creative and musical interests trumps what you know is “right” or best and wrong. A lot of times I’ll throw a part into a song that I know the timbre of what I'm playing might conflict with the timbre of another instrument of the pitch range...but it's just so cool that i have to do it. So thats where a lot of stuff comes that might not be sonically the best way to do things but its part of the artist's vision so you got to go there. If it sounds like I think about this shit too much, I do. [Laughs]

Was there a different approach to the tracks that had live elements on them? Ron Carter (famously) on the bass, Vinia Mojica on vocals, things that you were actually recording at Calliope?

No I didn’t take a different approach i just tried to make them fit into the record. It’s so weird that people love that record because I listen to it now and I’m in a completely different universe as a mixer, like how can I explain it? I feel like i was driving a Toyota and now I’m driving a Maybach, just in terms of perception, how I understand the process. And now I’m listening to that record and I'm going oh my god, how did I do that? But you cant get hung up on that.

And keep in mind one of the reasons that record sounds so cool is there was a lot of doubling of the samples with things behind them like harder drum sounds. You know when you listen to the record you perceive the sample as being the core of the thing, but in fact we doubled the kicks we doubled the snare to give them some more punch...

I think that’s what I was picking up on that quality of invisible instruments or instruments gel-ing together into an abstract groove...

Yeah, and the same with like, if there was a Fender Rhodes sample and that was the important part, sometimes I would do some stereo panning on it, just subtly, just to widen out the image. The thing about hip-hop of that era is that if you made it sound too wide and too big stereo, it just didnt sound right. It wasn't a lot of big reverbs on that kind of stuff, it just wasn’t part of the style. A lot of the stuff was consigned to a much narrower stereo field. In fact that's one of the things that gives the music its punch; it's coming up the middle so all the parts have to work together really well, rather than being spread out. And reverb tends to wash things out, and that was totally not a good thing at that point.

My impression from the outside is that a lot of the samples and jazz influences or inspirations for the album were coming from Q-Tip’s record collection — is that correct? Or were you also turning the guys up on source material from your own musical knowledge?

Well, Ali is the second cornerstone of the band, you know. Tip and Ali were the guys who made the music. Ali’s strengths — at that time, because Ali’s turned into a very good musician, and I say that as a lifelong musician! He’s taught himself a lot of traditional musical skills, which I love, and he combines that with his hip-hop sensibility. It’s beautiful. I don’t even remember the genesis of what track was whose, but it really was a very communal effort. We all know what their strengths were and Ali’s strength at that point, to me, was his beat-orientation, which is always so muscular. Ali has never pussyfooted around when it came to a drum beat. So I believe both of those guys contributed evenly to the record.

Having been so close to the tracks, do you have a personal favorite?

No I love 'em all, its funny I think everybody still loves those records. You know I was listening to the masters with Ali recently [because of the 25th anniversary] and he said “it’s like falling in love all over again.”

__

Edwin “STATS” Houghton is a noted music journalist and the former editor-in-chief of Okayplayer.com.