In celebration of the anniversary of Jodeci's debut album, Forever My Lady, we spoke with group member Dalvin “Mr. Dalvin” DeGrate and engineer Paul Logus, who both provided insightful account of how this classic album was made.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Donald “DeVante Swing” DeGrate Jr. and Dalvin “Mr. Dalvin” DeGrate began playing at Christ Tabernacle Pentecostal Church — their father’s church — in Charlotte, North Carolina. Their father, Reverend Donald DeGrate, Sr. was a groundbreaking Black televangelist on the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) for several years before his recording career took flight in 1979. That year, he recorded a hit song with his group, the Don DeGrate Delegation, titled “I Wanna Be Ready.” Shortly thereafter, he signed a recording contract with the Nashville, Tennessee-based WORD Records. During this period, Donald Jr. and Dalvin were traveling and performing with their father and other gospel artists. By the time they were teenagers, they were accomplished musicians and performers.

Around the time the Don DeGrate Delegation was taking off, Cedric “K-Ci” Hailey began singing at Tiny Grove Holiness Church, his family’s church, in Pageland, South Carolina. A few years later, Cedric and his younger brother Joel “JoJo” Hailey relocated to Baltimore, and they became integral members of a quartet-style ensemble, Little Cedric and the Hailey Singers featuring their father, Cliff Hailey. In 1983, they released their debut album, I’m Alright Now, on GosPearl Records. The following year, their group landed near the top of the Billboard Gospel Albums chart after they released their second effort, Jesus Saves. A year later, they released another successful album, God’s Blessing. During their stint together, the collective drew comparisons to the 1970s R&B quartet, The Chi-Lites. Fifteen-year-old Cedric was dubbed the Michael Jackson of gospel music due to his vocal genius. The family eventually moved to Monroe, North Carolina, and the brothers became acquainted with the DeGrate brothers. The first time JoJo met Donald Jr. and Dalvin was the mid-'80s, when they were performing with Tammy Sue Bakker.

When Donald Jr. was sixteen-years-old, he left home with aspirations to join Prince’s band in Minneapolis. Unfortunately, he was turned away and returned home to North Carolina. Upon recording their fourth album in 1987, Little Cedric and the Hailey Singers were auditioning musicians for their band. One of the musicians to audition was Donald Jr., who was soon selected to join. Within the same time frame, they shifted their focus from gospel music to R&B music, leading to the formation of Jodeci. One day in 1989, the Hailey’s and the DeGrate’s embarked on a trip to New York City with only$300 in their pockets and their demo tapes. They ended up at Uptown Records.

While holding an impromptu performance of their demo songs inside the offices of Uptown, they captured the attention of legendary record man Andre Harrell. By the end of the same day, they were given a recording contract. As they began working on their debut offering, the group would be accompanied by Paul Logus, a veteran engineer who worked with Al B. Sure!, Zapp, Slave, Tina Turner, Shirley Murdock, among other artists. His expertise became a valuable asset while assisting Jodeci by setting up the equipment that captured their otherworldly vocals.

On May 28, 1991, Forever My Lady was released. Peaking at no. 1 on the Billboard charts, the album spawned three chart-topping singles: “Forever My Lady,” “Come and Talk to Me,” and “Stay.” In celebration of the album’s 30th anniversary, we spoke with group member Dalvin “Mr. Dalvin” DeGrate and engineer Paul Logus, who provided an insightful account of how this classic album was developed.

The interview with Mr. Dalvin and Paul Logus were conducted separately. Both were condensed for clarity.

What is the story behind the forming of the group?

Mr. Dalvin: We’re all from Charlotte, North Carolina. Little Cedric and the Hailey Singers were K-Ci and JoJo’s gospel group, then there was this girl gospel group called UNITY, and then the Don DeGrate Delegation which DeVante and I played in. So, we met some of the girls from UNITY. Their names were Barbara Jean and Poo-Poo. These were some country girls as you can see from their names. Well, Poo-Poo was dating K-Ci before we even met. Barbara Jean would always tell us that we needed to meet K-Ci and JoJo. We heard about them before, but we hadn’t met them yet. We were all between the ages of 14-16. Barbara Jean and Poo-Poo took us to meet them. They had a little gospel studio joint, and next thing I knew K-Ci pulled a gun out on me. He thought I was messing around with Poo-Poo. I told him, “Man, are you serious?” My brother was actually dating her sister, Barbara Jean. I told my brother these dudes are crazy and that I was leaving. I left and DeVante stayed there with them. He would keep on telling me that they were writing songs, and he wanted me to come back to start working with them. I ended up coming back and a couple of months later we formed the group.

How did the group secure your record deal with Uptown Records?

One day we drove to New York, and within that same day, we got our record deal. We went to Uptown Records. When we walked into the building, we didn’t know anyone. We walked over to the receptionist, and we asked her if we could speak with an A&R. She told us that if we didn’t have an appointment, we couldn’t speak to one. But after a while, she finally let us through the door. We met this guy by the name of Kurt Woodley. We were in there playing him our music and this dude fell asleep on us. So, we woke him up and he told us that we had to do better with our sound. We began singing to him live in the office and G-Whiz from Heavy D and The Boyz knocked on the door and asked, “Who is that singing?” He went to go get Heavy D. After Heavy D heard us sing, he went and got Andre Harrell. We sung “Come and Talk to Me” and “I’m Still Waiting” to him live. The next thing we knew, he was taking us out to dinner. He signed us to a deal that same day.

Before you began working in the studio on your group’s debut album, what was the inspiration behind the making of the songs on your demo?

My brother D was dating this girl named Monica, and he wrote all of those songs for her. She ended up going into the Army, and she never came back. We used to do strictly gospel music back then. We never wrote any R&B songs until D wrote these songs for her. Monica actually has the original demo tape of those songs. He’s never seen her since they were in high school together. He let me hear the songs one day, and I told him they were dope. Our parents didn’t allow us to listen to R&B music growing up. When we would go and buy a Michael Jackson or Prince album, we would slide the album into one of the gospel record covers so they wouldn’t see it. My parents would come into our room and find them, and they would leave the little pieces of the record in the cover after breaking them. We would keep on buying the same records over and over again. We could only listen to their songs through our headphones. By listening to those records, that’s how we learned to do R&B music. Most of the songs were written before we left North Carolina. My brother was 16 and I was 14 when we wrote the songs for this album. The songs “I’m Still Waiting,” “Come and Talk to Me,” “Forever My Lady,” and “U and I” were on our original demo tape.

Paul, how did you become involved with this project?

Paul Logus: I came in on the tail end of Al B. Sure!’s record, Private Times...And The Whole 9!. It was really almost as an accident because a friend of mine was working on the record, and he just wasn’t available. I remember distinctly that it was the 4th of July. We were both working for the Hit Factory as staff engineers. They called me and asked, “Do you want to come in?” That was the beginning of me working with Al, and we were just locked in from there. I finished his record. Then he was like, “I’m doing this new record with these kids that got signed. Their name is Jodeci.”The funny thing is that we were all kids. Al was brought in by Andre Harrell. This was on Uptown/MCA. Al had this old soul vibe about him. He was brought in to reign in Jodeci and teach them the ways of how to make a record because they got signed. The album they made didn’t meet up to the standards of the label or something like that. The label wanted Al to oversee their project.

I remember Al showed DeVante how to make the record properly, which probably meant starting with his setup. It involved me engineering and recording it properly, getting the sounds together, and getting it captured properly. What we did with Jodeci was really sonically an extension of how Al and Kyle worked. They had a total system down. Back then, we had the brand-new G series 456 input SSL. It was a brand-new room. This was a multimillion-dollar facility. It was the top facility in New York City. The reason why we were there was because of Al. Al was the one that brought hip-hop into the Hit Factory. I was working on rock records before I worked with Al.

When you all began working together in the studio, how did you learn about the record making process?

Mr. Dalvin: We actually did the album over three different times. We spent months in the studio rerecording that album. We would turn in the different versions to the label, and they would tell us it wasn’t what they were looking for and to try again. Another four or five months would pass by, and we would turn in another version. They would say the same thing. By the time we turned in the last version of album, they told us it was something they could work with. This is when Al B. Sure! started to come around to help guide us. He told us to start making the music sound different. We didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. Andre would always tell us it was about the sounds. We were like, “What sound?” Eventually, we began to understand what they were trying to tell us. The last version of the album that was released only took us a week to finish because we had already written the songs. It was about getting our sounds right because the vocals were already done. It was us going back in the studio recreating the beats and the melodies. Guy was a big inspiration to us back then. They were the group we would listen to all of the time. Aaron Hall was a great singer, and we had the pleasure of hanging out with him. Uptown didn’t want us to go in the same direction as Guy. They wanted a group different. It was one of the reasons why we had to keep doing our album over and over again.

Can you remember the first studio session that you had with Jodeci?

Paul Logus: It was amazing because I thought it was on another level, almost beyond Al, in a sense, musically. I was impressed with the fact that they were so young, but they knew who they were musically. They were so damn good at what they did. It was just unbelievable. The thing that blew me away instantly about DeVante was how musical he was and what a virtuoso he was with whatever he picked up. I don’t think he ever played guitar before [and one day] I saw him pick up the guitar and he was doing stuff. I asked him, “How the hell are you doing that? You don’t even know how to play guitar.” He wasn’t as good of a singer as K-Ci and JoJo but he could sing. He had an ear that defied anybody I knew at the time.

When we would get around to doing vocals, he would sit down at the keyboard and come up with these chords. He would say, “You’re going to sing this one, Al.” We would go through, and we were stacking all these harmonies. It was really lush, lavish stuff. It was all the stuff you heard on the record. DeVante heard all that stuff in his head first, before he even put his fingers on the keyboard. There were so many things that impressed me about him. When you showed him something, he picked it up and he made it his own like he was an expert at it. He picked up Al’s systems for recording with all the keyboards and everything. We had a rack of stuff. We had one of those A-frame rack things, maybe two of them. He’d never worked that way before, but when we showed him how to do it, he was like, “This is my shit now.” He made it his own, and he took over. He did it.

What were some of those things that you did sonically when you drew inspiration from them?

I was creating a sonic stage and a mental image in my head of a sonic stage for them which the record company didn’t react to, initially. But I heard things really big like it was a performance on a stage that didn’t exist in front of me. I was making stuff super lush and deep. I was putting on a ton of stuff: panning, bass shifting, stuff on the vocals, and I made the vocals sound huge. Anything I could think of, I could just do it because they were kids and they didn’t know, so I was like, “Screw it. I’m just going to have fun.”

I got two 24-track machines, and we were just going to have a blast and get creative. We had all these keyboards and a guy who could play his ass off. I was going to have fun. I mean I was just coming up with all kinds of crazy stuff with the drum sounds, vocal sounds, and the keyboard stack. I was always trying to get different tones on things. I was running stuff through a guitar amp, phase shifters, and electronic flangers. I would do a sub-mix of a track, and then I would put it on a two-track half-inch machine. Then, I would run it back into the 24-track, and then I would synchronize them by ear. Then we’d have this flanging sound over the whole track. Anything that I could think of. I would flip the tape over and record reverbs and stuff and there would be reversed reverbs coming in and things.

With them being so young, what impressed you most about their talents as a collective?

I was blown away because they sounded like seasoned pros; they didn’t sound like kids. All of them acted like they were like 10 years older than they were in terms of their talents. They were all virtuosos. K-Ci had an old soul vibe about his voice. JoJo sounded younger to me, but they obviously worked incredibly well together, because they had been singing together their whole lives. There would be times when I’d record both of them at the same time, and they would flank in and out of each other around the microphone because one knew what the other one was going to do instantly because they had just been doing it for years together. It was like watching a completely seasoned band that knew each other.

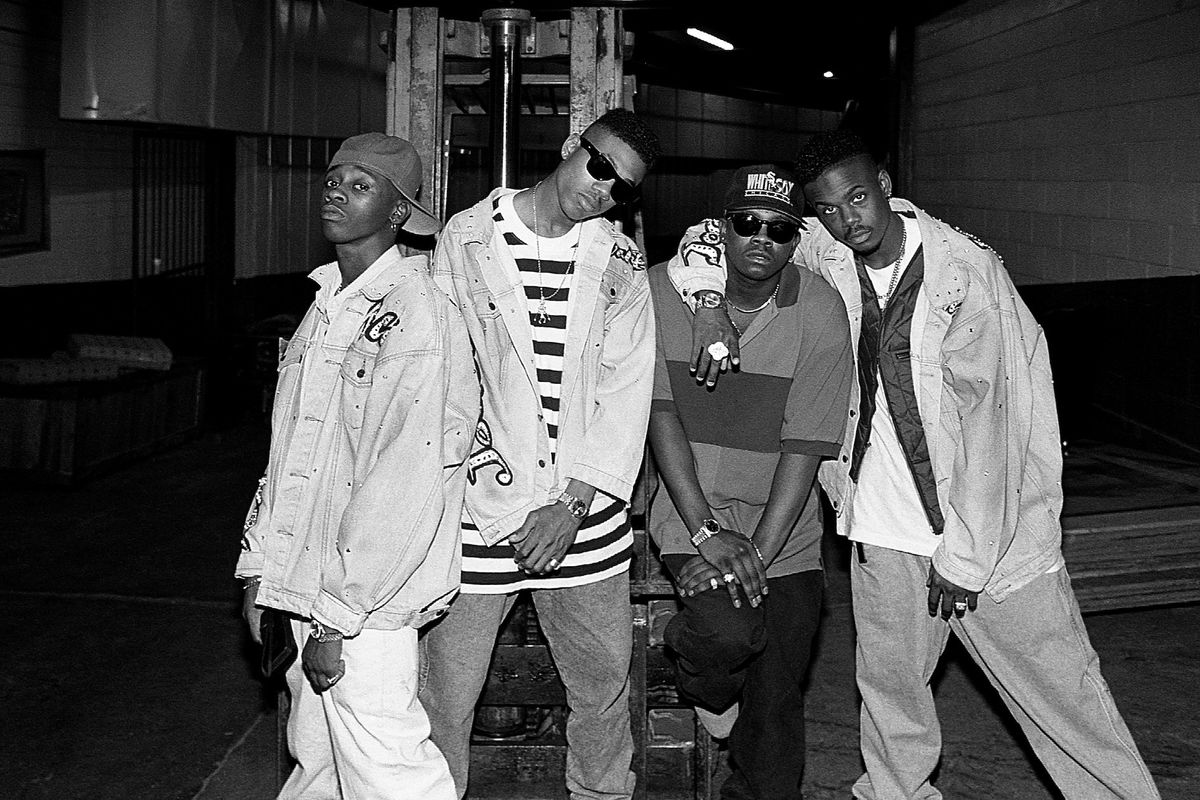

"The thing that blew me away instantly about DeVante was how musical he was and what a virtuoso he was with whatever he picked up. I don’t think he ever played guitar before [and one day] I saw him pick up the guitar and he was doing stuff," Paul Logus said. Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

"The thing that blew me away instantly about DeVante was how musical he was and what a virtuoso he was with whatever he picked up. I don’t think he ever played guitar before [and one day] I saw him pick up the guitar and he was doing stuff," Paul Logus said. Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

Earlier you mentioned that the typical studio routine you had lasted between 12 and 18 hours. Did that last for months?It would go on for quite a while. I don’t remember exactly. I don’t remember how much time we spent on that record, but it could have been a month or two. There were multiple things happening. We might stop something and do something else that was more pressing, or if an opportunity came up. We did a thing for In Living Color’s Fly Girls which had Jennifer Lopez in it back then. I don’t think it ever got released, but I have it because Jodeci was singing on it. They were singing all the Fly Girl parts for them to sing, and I don’t think they ever used it on the TV show. But other stuff would happen and the label would say, “Oh, we need to do this.” We would stop what we were doing and flip around. We spent probably a year or two easily in that room working with Al, DeVante, and Jodeci on many, many different things.

They did all the backgrounds with you in the studio.

Yes. They recorded everything with me in the studio. All the music from nothing being on the tape to being all recorded. Al started them on a process with their backgrounds, which I thought was really cool. It was a thing that he learned from Quincy Jones. Al tipped them off to this trick. Then, we took it and embellished on it. DeVante took it and flushed more on it. We were trying to make things sound really organic and have depth to it sonically. We would have this one take, and we’d have these multiple rhythms we could synchronize together in these 24-track pieces of tape so we would record everything. We’d record all the music on one to 24-track tape, and then we would synch routine and put some safety down, and we would lock up another one. Then, the second reel would have just a rough mix of what was on the first reel like all the instruments just because we never used to fill up the music on the first one. So, on the second one was when we’d put up two faders and we got their music. Then, we would go through and on that second reel, we would do backgrounds. We might put a scratch lead vocal down or something, and then we would do the background. But on the backgrounds, just to be really slick, we might do four tracks of one note, and then maybe two tracks of one note and the two tracks are the same note, but standing back a foot or two or three.

We were trying to recreate an image of a choir, which, if we had a choir of people there, we all wouldn’t be one foot away from the microphone, we’d be standing over there, a couple of feet away. If we got a choir sitting there, we’d all be hitting the microphone differently. The Quincy Jones trick was, if someone stood in different positions on the floor like you’re trying to recreate a choir and record it like that, you load it up with 16 tracks or 24 tracks, and it’s going to sound really cool and that’s what we did.

I wanted to make stuff sound cool, and then DeVante was playing all these crazy, cool rhythms with his crazy fingers on the keyboard and that sort of stuff. Sometimes I’d be like, “Oh my God. How are you even playing this?” He would just be playing inverted chords and whatever crazy stuff along with it. He’d say, “We’re going to do this cluster of notes on top of everything that’s going on.” I didn’t get it at first. He would play the chord, and then he would play the one-note inside the chord, and that was your note. Then, K-Ci or JoJo would go out there, and they would sing that note. After that, they would do it maybe two or three times. Then, we would do another note and do it a couple of times. Then, I would pan it out, pan it left, right, center, do different things to it, put some effects on it, and then make it balanced, so that it all sounded like it was part of a man-made choir of one or two guys singing. That was always the goal for me.

When you all were recording in the Hit Factory, which studio did you all primarily work out of?

We started off at the Hit Factory Times Square which is where most of the stories I’ve told you took place. The mixing part mostly took place in a studio called M1 which was like a spaceship. It didn’t have a studio part to it. There was a control room and a lounge. That was it. There was a long rectangular thing. It really looked like you were on a spaceship inside that. Then, across the hall from that one, was 83, which was a giant wood room studio. That’s where we did a little bit of recording. “Come and Talk to Me” was remixed in that room. We did all kinds of wacky stuff there. I was making people do things to enhance the drum tracks and whatever. We were having fun with it and getting tribal. We were doing foot stomps and hand claps, anything to be progressive, but with body parts. That was a lot of fun.

Could you talk a little bit about some of the folks who visited the studio and those experiences?

Once we were a little further into the record, there would be people coming through, some of whom I did not know at all, and it would just be a bunch of girls or something and maybe some other guy friends. Missy Elliott was there and Usher was around. There were lots and lots of people around. I also remember that Al was a superstar, so there were people around Al. I met Kim Porter when she was with Al back then. I remember she was there in the midst of the Jodeci record. The thing that was interesting was that we were maybe halfway into the record or something, and I hadn’t seen anybody from the label yet. Then one day, the label guys come in. It was three guys who were dressed really sharp. One of them was Andre Harrell, and I think the other two guys were from higher up at MCA Records.

Everybody was like, “Oh, boy. What’s going on?” We had done something that caused them to come to the studio. We had to put the hot dogs and the beer away. Everybody had to clean up. I think Al was around for part of this. The big concern was that “Forever My Lady,” which was about him, was way too mature for Jodeci to do, if you can believe that. They weren’t 18, none of them were 18 yet, maybe 16 or 17 at the most. They were really worried that young kids putting out a song about having babies sent a really bad message about their generation. The label wasn’t sure if they wanted it. I really think they were thinking about taking it off the record. Everyone was like, “Oh no! That’s a really good song.” They were worried it was going to get knocked off but obviously it didn’t.

There was definitely controversy over them singing those lyrics.

You sing, "so you’re having my baby" and you’re 17? Really? That was a testament to how mature Al was with everything. He was writing all this mature stuff because he was a grown man. He was having kids. He was having a baby. He was already a successful artist. I think Benny Medina might have been his manager then. Al would be like, “Get Benny on the phone. We need to talk about this. They’re thinking about taking my song off the record.” Al was the man creating somewhat of a light blueprint for Puffy. Towards the end of that record was when Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs came around. I’d never seen him before that. Jodeci went from being a bunch of crazy, giggly kids to being even more serious and being styled by the newly emerged Puff Daddy. He started them with the baggy clothes and pants. He made them all wear the same thing. They never had worn all the same thing before. He gave them an image makeover which was very revolutionary, I think.

How did they dress before Diddy came around?

They would dress in jeans, t-shirts, and sneakers. They just dressed like kids. The other thing was that they didn’t have money when they were there. They’d been put up in a house somewhere in New Jersey, and they were driven in and out of the city every day. They were kept under wraps, and they were itching to get out. We were working right in the middle of Times Square where The Hit Factory was located. It was right on 42nd street. That area was really rough and raw during the nighttime. It’s much different now. It’s Disney now compared to back then. I was surprised that they didn’t have a legal guardian there with them because none of them were 18.

During the course of making the album, was there a lot of improvisation?

Yes. DeVante was just so fluid on the keyboard that we didn’t get the impression he was struggling with anything ever. None of them were struggling at all with anything. They were making up stuff on the spot. Besides the record, we made a show tape and we made some other things, and we did something for a TV show. We recorded a bunch of things, and they were just making up stuff on the spot. It would just get recorded really quickly. DeVante could hear stuff faster than he could play it. He fucking knew exactly what he wanted to do, and he couldn’t play it fast enough to get it on tape. There was such a vibe, and we were having fun and goofing off, but when it was time to record, we’d sit down and the stuff would sound great. There was stuff just pouring out of him. He inspired me to get sounds that I got. I think some of that inspired him. As genius as he was, he was still learning and we’d teach him things. He learned from Al, and he learned from me a little bit. I’m a musician, too. I got off on listening to him play stuff because he was just so good. I loved listening to his chord progressions and his arrangements on stuff. Nobody was doing anything like that. It was futuristic.

Let’s go in-depth about the making of some of the songs from this album.

Mr. Dalvin: “Gotta Love” was one of the first songs DeVante wrote. I remember the record company didn’t want us to put that record out. Puff was the one who encouraged the label to release the song. The song didn’t do well on the charts, but it was a fun song to do. Puff was actually one of the dancers in the video for the song. Andre Harrell didn’t really like the song, but Puff wanted it to be released. Andre told him, “If this song doesn’t do well, you’re fired.” [laughs] The song didn’t really do well, and I remember Puff was dancing hard in the rain in the video. He was trying everything to make it work. Puff goes 100% in everything he does. We shot the video for this song and “Stay” within the same day. We hadn’t shot a video before that day and it was a long day.

“Forever My Lady” wasn’t even a song at first. It was an interlude for the album. The record label actually made us turn it into a song. This is when Al B. Sure! came in with those orchestral sounds to strengthen the record. If you heard the first version of the song, it sounded just like “Piece of My Love” by Guy. We had to keep doing it over again until the record company was happy with it. When Al came in, he brought in the sounds that we needed to use. He brought in a lot of the sounds Kyle West used on his debut album. We weren’t really into sounds, but we were into that New Jack Swing sound, even though we came from North Carolina. Al brought in all of those orchestral type sounds and different instruments. I remember the most controversial moment from the Forever My Lady album was the first line in the song “Forever My Lady:” "So you’re having my baby." I remember no one wanted us to sing that because people would think we were old when we were just kids. It was the most controversial line, but it made sense. It helped to make our album a success. K-Ci didn’t want to sing it and DeVante hated it. Al B. Sure! actually wrote that line for the song, though.

“Stay” was a song DeVante wrote for Al B. Sure!’s [Private Times...and the Whole 9!]. He didn’t want the song, and DeVante told me to change the beat because it sounded totally different from the version you hear now. So, I came up with the slow melody for the track. D told me that he didn’t know if it was going to work or not. I switched up the drum pattern and played the keyboards on it. I told him, “Let’s go ahead and try it.” The first version of the song was entitled “Touch You.” If you go back and look at Al B. Sure!’s second album, you’ll see a song on there with the same title. And that song was actually “Stay.” Al kept “Touch You,” and we made “Stay.”

“Come and Talk to Me” was the first song he wrote for the album and it was for that girl named Monica. DeVante played all of the instruments on that song and wrote the lyrics for it. The first version of the song sounded nothing like the version you hear today. It sounded like a New Jack Swing track but with the same tempo.

“I’m Still Waiting” was another song that DeVante wrote for Monica, but when we got to New York, we did a remix for the song. I was the one who did the remix for that particular song.

I remember Andre Harrell and the record company not wanting us to put “U and I” on the album because he said a song with the title “U and I” [would] never hit, but we put it on there any way.

“Xs We Share” was an album filler, but my brother used to love it. We had so many different versions of it. The version the label picked for the album wasn’t our favorite version at all. This song went through so many changes. The only time we ever performed the song was on the show In Living Color.

As you look back 30 years later, what are your feelings about the impact that Jodeci has made on popular culture?

I feel like we’ve paved the way for a lot of these groups. We’ve helped to make it easier for them. Back then, R&B music was kind of dying out, and I feel like we gave it new life. We didn’t follow a pop trend like Boyz II Men did. We stayed true to who we were and true to R&B music. We did open the door for many groups that came after us. We helped to keep R&B music alive from a group perspective.

__

Chris Williams is a Virginia-based writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, Red Bull Music Academy, EBONY, and Wax Poetics. Follow the latest and greatest from him on Twitter @iamchriswms.

"The thing that blew me away instantly about DeVante was how musical he was and what a virtuoso he was with whatever he picked up. I don’t think he ever played guitar before [and one day] I saw him pick up the guitar and he was doing stuff," Paul Logus said. Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

"The thing that blew me away instantly about DeVante was how musical he was and what a virtuoso he was with whatever he picked up. I don’t think he ever played guitar before [and one day] I saw him pick up the guitar and he was doing stuff," Paul Logus said. Photo Credit: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images