Photo Credit: @nayion202 on Twitter

We spoke to filmmaker Jacob Garibay about his documentary which tells the story of how New Balance became the dominant sneaker of Washington, D.C. natives.

A lot can be said about a person by what kind of shoes they're wearing. And in Washington, D.C., New Balance is the sneaker of choice. It represents prosperity, comfort and style. Based in Boston, Massachusetts, the brand has been known for its comfortable running sneakers since the late '70s. When stores in the D.C. area started selling the shoes in the early ‘80s, the brand’s reputation went to a new level.

In his documentary short, DC’s Shoe: The Origin of New Balance in Washington, D.C., filmmaker and musician Jacob Garibay spoke to other natives of The District about how the sneaker brand rose beyond its Boston roots to represent a Black metropolis. New Balance has become as synonymous with The District as the percussion-heavy sound of go-go music.

In the documentary, interviewees share what made the brand special for them and how New Balance sneakers found a space in their lives. You hear a wide range of stories, including tales of people wearing New Balance sneakers to see D.C. go-go band Rare Essence in the ‘80s to younger D.C. natives talking about their parents championing the sneaker brand to this day.

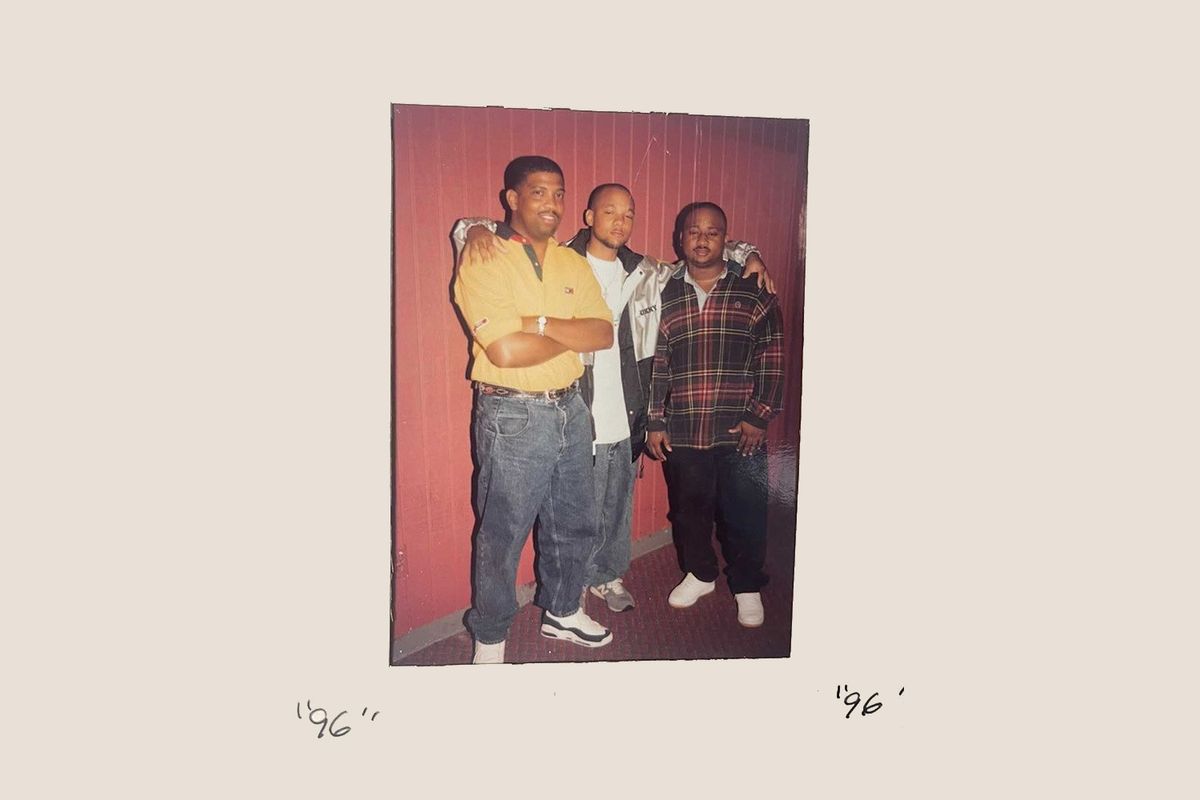

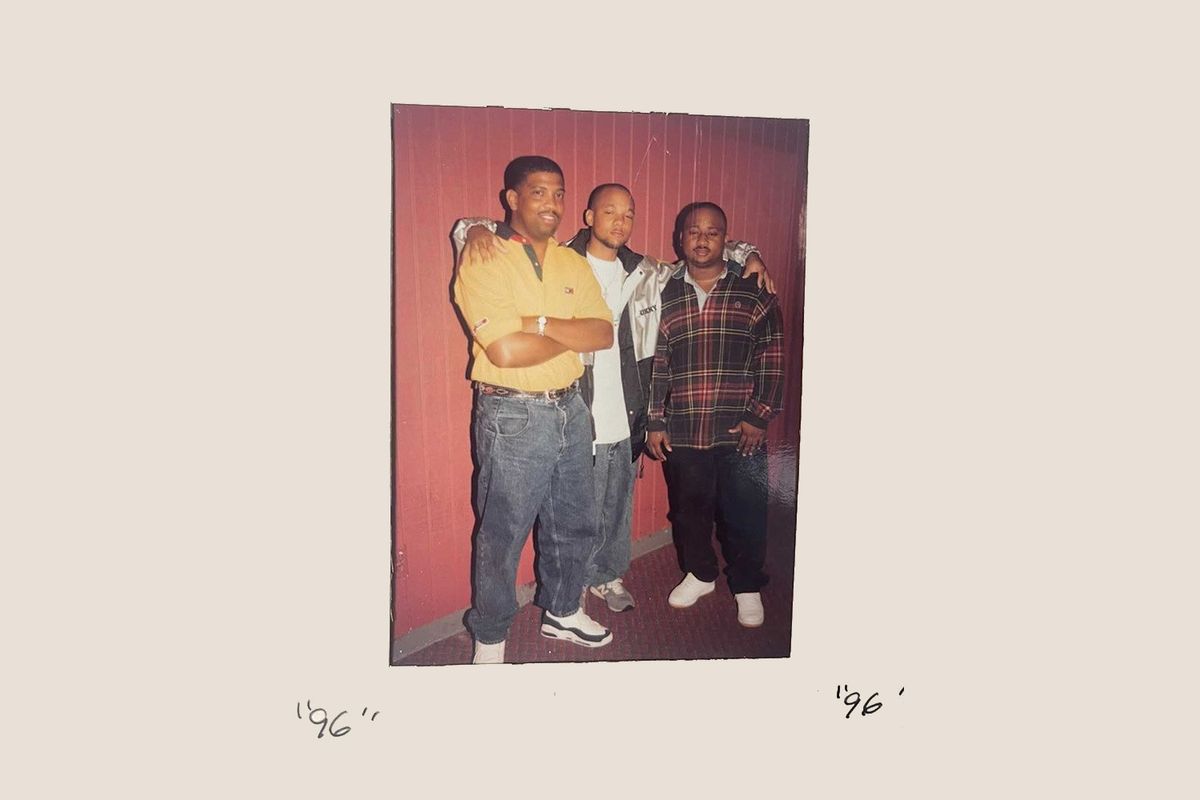

Through his research for the documentary, Garibay asked his followers to share throwback pictures of D.C. residents wearing New Balance shoes. His social media accounts were flooded with pictures of people wearing the sneakers at a wide range of events, from “go-gos” to neighborhood block parties to even the red carpet of the BET awards. No matter where a person from The District went, people knew who they were because of their New Balances.

Garibay, 27, spoke with Okayplayer about his inspiration for exploring the topic, how its perceived value made it a fixture on blocks throughout The District, and how he believes the brand can do more than sell shoes in the city where it is beloved.

Jacob Garibay: I was born and raised in D.C. I lived there my whole life until I moved for college to Temple University in Philadelphia. I was in D.C. public and charter schools my whole life. I was never someone who felt I had to go out and find my culture. I never felt like I didn’t have an identity. Apart from being Black and Mexican, I identified as somebody from D.C. Although my Dad’s side of the family is Mexican, my Dad was born and raised in D.C. We’re second generation D.C. natives on both sides. My Mom is Black. I felt the unique culture of D.C. more than anything. Not seeing the world much through traveling before college, I was under the assumption Black culture was D.C. culture.

New Balance sneakers are to D.C. like LA with [Converse Chuck Taylors] and Nike Cortez. For me, New Balance wasn’t something we looked at as our unique fashion, it was like everybody wore New Balance. I didn’t want to be the guy without New Balance. It was around fifth or sixth grade where everybody had Nike Boots.

Photo Credit: Karim Mowatt

Growing up, you’d hear stories about New Balance from different people. From the comments on videos I posted, people said that if you had money in the ‘80s, you’d see people in pictures at go-gos in New Balance. That’s how we pointed back to us as the city that started it. We have pictures from the early ‘80s of people wearing New Balance to the club or go-go.

New Balance was the first $100 sneaker in D.C. It was a status symbol. NB put out a $100 running shoe in 1983, the original 990. Two years later the original Nike Air Jordan 1 was still only $65. If you wanted to feel like you were getting money or of status, you would see a New Balance or Air Jordan 1. It was a more expensive shoe. The neutral color was gray.

My first interviewee told me that if you’re on the block all day, you want a pair of shoes that’s comfortable and something that wouldn’t hurt your feet after four or five hours. That shoe was New Balance. He also pointed to Asics and made the point that D.C people mostly got their style from tennis players.

If you think back, Sergio Tacchini was fashionable. People wore tracksuits in pale, muted colors. In the late ‘90s Baltimore became fond of New Balance and in the mid-to-late ‘90s, Philadelphia got into it. Before current trends, only London and Japan got special colorways.

When I initially started the project, I asked people to submit pictures on Twitter, and got a ridiculous amount of responses. Doug, a guy I interviewed, was on the 2008 BET Hip-Hop Awards red carpet with some friends. All five of the guys had on New Balance 992 sneakers.

The camera’s going off for the picture of them captured the reflective material on the 992s. As he told me, “We weren’t making a statement; it was just popular in the city.” D.C. native LoLa Monroe walked up to Doug and instantly went to say "what’s up" to him.

I think people are really happy that they’re culture is being represented. I think at this point, more than anything, they realize the buying power they have. They’re like we’ve done so much for New Balance, what are they doing with the energy we give them? We made them hundreds of millions over the past 30 years. What are they doing in return?

Even with branding and marketing, they signed Jack Harlow and they’re trying to expand the lifestyle demographic beyond communities. How can you do it more authentically? Even though you don’t have to put in as much marketing dollars, how can you show people in Washington D.C. real love? We don’t want shoes. We want representation. Make someone here the face of a campaign. Give out scholarships and grants.

Put your best foot forward. Do it as best as you can. I didn’t feel any pressure. That felt like a good thing. Now I have pressure with my next project. I also want to get better and make sure I have a better camera. I started this doc in September 2021 and finally put it out this year. I didn’t go my whole childhood wanting to make movies, but I had a camera and access to a camera for my job. I did video and photography work. I had a Sony A6500 camera. It was something that came along with my job.

I’m trying to build out a small team. I did 90 to 95% of the shooting, editing and setting up own takes for this project. I am looking for someone to help fund the next project so I can pay those people. I made the screening free and put it out on YouTube. Access to information about history is something people shouldn’t have to pay for. It’s about an underrepresented group of people and something I don’t think people talk about enough.

__

Michael Butler is a Panamanian writer from Augusta, Georgia and has written about culture for publications like Remezcla and Lonely Planet. When he isn’t eating ripe plantains, Michael is a fan of the Atlanta Hawks and reciting every line from The Five Heartbeats.