We spoke to Lance Scott Walker, the author of the thorough but breezy DJ Screw biography, A Life In Slow Revolution.

When it comes to DJ Screw(real name Robert Earl Davis Jr), it’s sometimes difficult to separate the man from the mythology. The late Houston producer pioneered a new frequency in hip-hop by slowing music down to a snail’s pace, bleeding the pain out of rap vocals by stretching them out like a game of tug of war.

Screw would typically stack up to four different songs simultaneously, so their unique layers of hiss and melody could fuse into a new form, while his name was based on the fact he’d scratch out songs he didn’t like on a vinyl with a rusty screw. But following his tragic death at the age of 29 in the year 2000, reports suggesting it was the result of a codeine overdose consolidated a legend that Screw’s woozy "chopped and screwed" mixes were best experienced with a double cup in your hand.

To have created music so immersive, and sedated to the point of psychedelia, it was assumed the creator had to have been out of his mind, operating in his infamous Wood Room home studio on a different time zone to the rest of us. I’ve honestly lost count of the internet posts I’ve read telling me Screw’s music doesn’t make sense unless you listen to it stoned. Yet what’s so great about veteran writer Lance Scott Walker’s long-awaited DJ Screw: A Life In Slow Revolution book (which was published today) is how it demystifies all this, treating its subject less like a mysterious campfire tale and more like a human being.

“Drugs were part of the journey, but they were far from the driving force,” Walker told Okayplayer. “He was slowing down records before codeine or promethazine ever came into his life. The idea of creating something new on top of a pre-existing tapestry of sound was something that sat deep inside of Screw. Remember: this man created thousands of tapes. He was insanely prolific and rarely slept. He never would have been able to make music at that speed if he was just on lean all of the time. “

The book — which is a breezy combination of biography and oral history — is based on years of interviews with Screw’s friends, family, and collaborators within the Screwed Up Click brotherhood. In its pages, we learn how scared neighbors in Houston called the police to complain about the hundreds of cars pulling up to Screw’s house to purchase his cassettes, assuming he was a drug dealer; Screw’s love for eating Lunchables; his terrible driving skills and car speaker system that had bass so loud it could be heard from miles away; and a big heart, which saw Screw create an original tape for a young fan dying of cancer.

Before I read the book, my mind went blank when it came to understanding who DJ Screw was outside of the music, but now I finally feel like I know who Robert Earl Davis Jr was.

The following interview with its author Lance Scott Walker has been condensed for clarity.

I always sensed Screw was a big G-funk guy. He seemed to get a lot of pleasure out of turning the sunniness of those songs into something darker and more bluesy, right?

Lance Scott Walker: He grew up on his mother’s blues, funk, and R&B records. That was his diet and he stayed attached to his mom’s record collection throughout his career. If you listen to his mix, Late Night Fuckin Yo Bitch, the track selections are Blue Magic, Bobby Womack, Parliament, and Teddy Pendergrass. These were all things he carried over from his mother’s record collection. It meant so much to Screw to do that. His music genealogy came from the same place as G-funk, so he easily connected with artists like Above the Law, Spice 1, and Ice Cube. The temperature and the speed of this music really appealed to him.

When Screw moved to Smithville, Texas, there wasn’t a lot of opportunity. Being a DJ gave him a purpose. Every parent wants to see their kid get interested in something, right? Well, Screw’s mom was an incredibly tolerant woman. Screw was literally destroying her records by scratching them up with a screw, but she was just happy her son was not making any trouble and was safe inside the house.

Screw is often presented as reclusive and married to his work. Is there some truth to that?

His work ethic certainly made him a recluse to some degree. He wasn’t a public figure. He wasn’t marketed properly. He didn’t have a team behind him putting his image or persona out there. It meant that others filled in the blanks in their minds of what he was all about and why they didn’t see him around town. Really, he was just working. It wasn’t that he was reclusive and didn’t like being around people, he just liked being with his loved ones, creating music. There is this mythology about who Screw was, but not a lot about the community of people who were actually around him. It was important for me that their stories were told; that’s really what was missing from the DJ Screw’ story.

Kay-K, Big Hawk, Fat Pat, and DJ Screw for the Dead End Alliance album shoot in 1997. Photo Credit: Deron Neblett.

Kay-K, Big Hawk, Fat Pat, and DJ Screw for the Dead End Alliance album shoot in 1997. Photo Credit: Deron Neblett.

I love how your book delves into Screw and the shout-outs he did to his community over all the mixes. Dude might pay tribute to the mailman or thank his dealer for the weed he just dropped off. It really broke the fourth wall.

There is a lot of times you listen to Screw tape and you hear Fat Pat or Lil Keke or E.S.G., just someone who can go on and freestyle forever. But sometimes there are other people in the room too. Maybe they’re not part of the Screwed Up Click, but just a neighbor who popped over, right? Screw just goes around the room, pointing at people and shouting them out. It brings you right into the room with him. You feel the camaraderie.

One of my favorite Screw mixes is what he did to 2Pac and Thug Life’s “How Long Will They Mourn Me?” The way he slows down the vocals seems to find new layers of pain. He didn’t just play with the tempo of music, but with language too, right?

He bled the music. He was bleeding something out of the music that he didn’t quite hear when it was at regular speed. He takes something pre-existing and figures out: how can I bend this? How can I warp the time here? How can I run something back when a line is important and extend the phrase? That was his way of tearing open the song. Ripping open the fabric of the song so you can see the insides of it.

I also love how Screw would mix in the 808s as scratches. You’ve been doing research for this book since 2005, what were some of the studio techniques you learned about Screw that blew your brain?

Beat matching is one thing, but going through and looping beats smoothly while you are also talking is hard. He would connect two or three records for a long stretch of time, just so people could freestyle over it. That takes a lot of skill and discipline to keep under control. He found new rhythms out of the echo or just the staccato of a song responding to itself.

A lot of people shared stories of Screw nodding off to sleep at the turntables. Someone would wake him up, he shakes into life, and he is still completely on beat! He knows where he is on the song despite only just waking up. That’s genius. I use testimony as well as freestyle lyrics for the oral history. I wanted to take disparate pieces and chop them together; I guess I wanted this book to feel like a Screw tape.

The book suggests Screw’s death wasn’t just to do with drugs, but a result of being exhausted and forgetting to exercise. Is there a cautionary tale here?

There’s one story about when Screw went to the hospital and he just slept and slept. The nurse says, "This guy’s problem is he’s tired. He needs to rest.” It is a lesson in moderation. But when collaborators talk about Screw, well, of course they all want him to still be here, but they also say he died doing what he loved. How many people get to do that?

Does the "Wood Room" deserve to be ranked alongside "The Dungeon" as one of the South’s great rap studios?

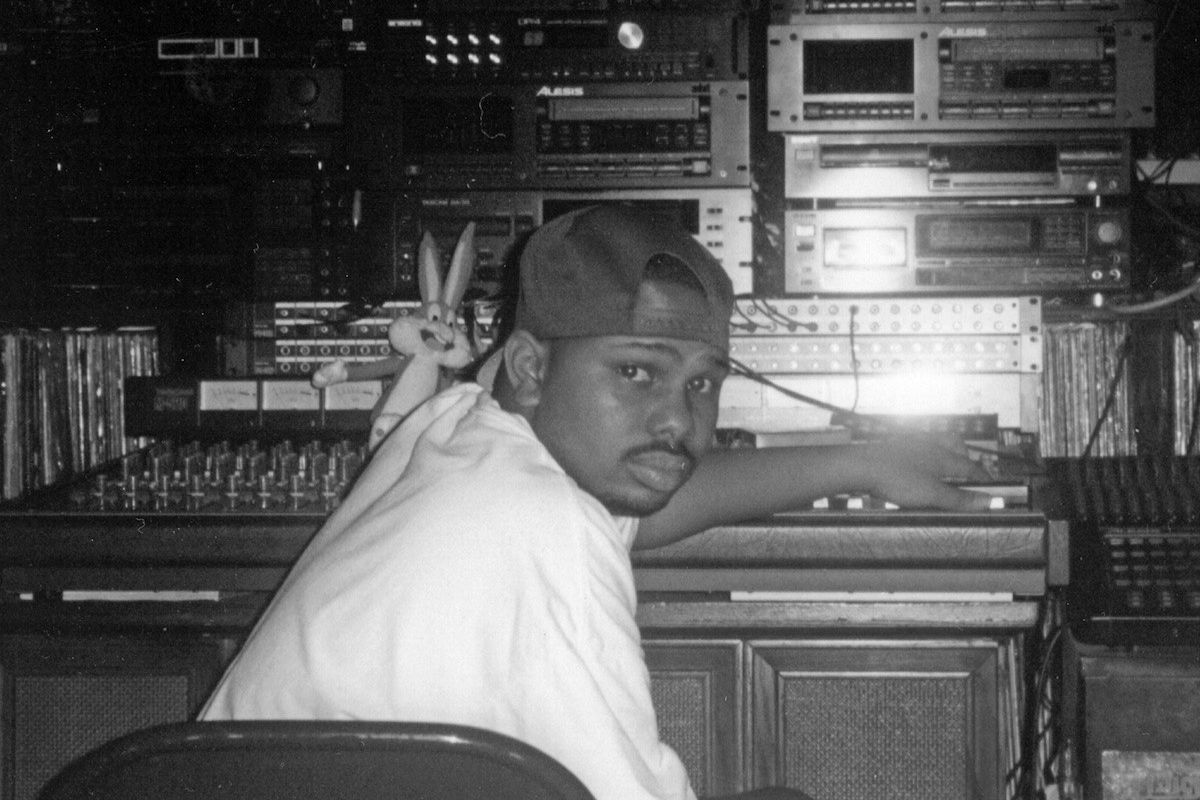

One hundred percent. The photo I chose for the cover of book was chosen for that exact reason. Say you went over to Screw’s house and someone else let you in? You came into the house, when you turned corner and went to Wood Room that is exactly what you saw. You saw Screw at that angle with the wood panelling behind him. The Wood Room is fabled. It’s a place of creative magic. A special room that brought something great out of everyone who walked inside. He was only in that house for a few years, yet it resulted in thousands of hours of music.

Although Screw sold a lot of tapes independently, his mainstream success seemed to happen mostly after his death. What do you think he would have thought about influencing artists like Beyoncé, Solange, Mica Levi, and Travis Scott?

He would have loved it, but he wasn’t looking for fame. Screw is a student of music, and he knew enough about music to understand the BS that accompanied it. He knew what he wanted and he knew what he didn’t want to do, too. He didn’t want the trouble of changing up what he was doing, to sign with a label or be part of one. Remember: he was earning enough money independently. He sold two million copies of June 27th from his front porch, with his girlfriend Nikki [Williams] doing the dubbing. He didn’t need a label.

How much unreleased music is there? Could something as good as Screwed Up Vol II be in someone’s loft right now, gathering dust?

There is just over 300 released as part of the Diary of the Originator series, but I would say there’s 100s of Screw tapes that got lost. Some melted in the Texan sun, others are in someone’s closet, waiting to be discovered. We find a new one every year. It makes Screw still feel alive. I have no doubt there’s classics we haven’t heard yet.

What is your big hope with this book?

I just want people to understand Screw the human being. There’s so many stories of how he looked out for people. Took care of rent, put money on the books for people when they are in jail, paid for groceries. That is another reason why he never slept; he was so focused on making others feel like they were his best friend. Even though he has been gone for 22 years, none of them ever lost that feeling. They all remember how he made them feel. My big hope for the book is those people who knew Screw get that same feeling from reading the other recollections in the book. That’s all.

__

Thomas Hobbs is a freelance culture and music journalist from the UK. His work has appeared in the Guardian, VICE, Financial Times, Dazed, Pitchfork, New Statesman, Little White Lies, The i and Time Out. You can find him on Twitter: @thobbsjourno

Kay-K, Big Hawk, Fat Pat, and DJ Screw for the Dead End Alliance album shoot in 1997. Photo Credit: Deron Neblett.

Kay-K, Big Hawk, Fat Pat, and DJ Screw for the Dead End Alliance album shoot in 1997. Photo Credit: Deron Neblett.